When more than 2 feet of water flooded Sylvia McMillan’s house during Hurricane Harvey, she knew exactly what to do, she said.

This was the second time her Norchester home had flooded in less than two years, so she had recently been through the same process of filing flood insurance claims and cooperating with the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

McMillan said many have asked why she chooses to stay in a neighborhood where she has taken on so much damage out of her control, but the home her husband built nearly three decades ago is paid off. Now widowed, she said she does not want to leave behind the place where she raised her family and invested so much work.

“I’m a firm believer there’s no secure place,” McMillan said. “Things will come and go. A flood is devastating, but they’re still material things. Now, will I take a third flooding? Maybe not. It’s a lot of work.”

Despite her choice to stay, dozens of Norchester homeowners have sold their flooded homes—some to investors intending to flip houses for a profit and at least 47 others since 1999 to the Harris County Flood Control District as part of its home buyout program.

The intent of the HCFCD’s voluntary home buyout program since its inception in 1985 has been to purchase properties and replace them with community parks, vacant lots or natural wetlands. This allows families at the highest risk of flooding to relocate, eliminates future flood damage and allows the flood plain to store stormwater, according to district officials.

James Wade, the manager of property acquisition services at the HCFCD, said the district has purchased about 3,000 properties countywide that meet buyout criteria in the last 35 years, but another 6,000 remain on a list of properties they are interested in purchasing.

Of the 410 home buyouts the HCFCD has conducted in the Cypress Creek watershed, 241 have been in Cypress neighborhoods located along the creek, including Grantwood, Norchester, Lake Cypress Estates and Windwood. In the same 35 years, more than 13,200 homes in the watershed flooded, so about three buyouts have taken place for every 100 flooded homes, according to district data.

“Our buyout program focuses on areas that are several feet deep in the flood plain, ... basically places [that] should have never been built to begin with,” Wade said. The need for buyouts

HCFCD Deputy Executive Director Matt Zeve said when homes are situated low in the flood plain and no other flood mitigation projects will reduce the risk of flooding, home buyouts can be the best option.

As much as 60% of Harris County was developed prior to the implementation of flood plain regulations in the late 1980s, according to the HCFCD.

“Unfortunately, there are subdivisions that were developed prior to the system of regulations that was developed, and they were built in places where they really shouldn’t have been built,” said Jim Robertson, a member of the Cypress Creek Flood Control Coalition board of directors. “[Home buyouts] are clearly a correction [to past mistakes].”

The HCFCD’s goal is to own every property in neighborhoods of interest, clear out all infrastructure and preserve it as open space, Wade said, but this is difficult because of the voluntary nature of the program. In Cypress, Grantwood has had the most buyouts at 135 between 1999-2019, and a county park has been installed in the neighborhood.

The district has the option to use eminent domain to force homeowners out of the flood plain if HCFCD officials believe lives are in danger, but federal grant funds are at stake in that scenario, he said.

“At what point are we, the county, being neglectful to allow folks to live in harm’s way in certain situations? How can we allow them to be in such a risky situation? It’s a gray area,” Wade said.

While home buyouts may help correct past development mistakes and offer an option to homeowners, local flooding experts agree it is not an ideal long-term solution for Cypress Creek’s chronic flooding.

“A lot of folks have had repetitive flooding, but is it cost effective to buy, demolish the home, relocate the family, pay the relocation costs and whatnot—or could there be a project to ease the flooding?” Wade said.

Funding the program

Home buyouts can be completed through three different programs. Community Block Development Grants are funded by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban •Development, while FEMA funds the Hazard Mitigation Grant and Flood Mitigation Assistance programs. Wade said about 98% of funding for Harris County buyouts have come from FEMA grants.

Because more funding is available in the wake of a presidentially declared disaster such as a hurricane, Wade said large buyout waves are influenced by federal disasters. In response to Harvey, the HCFCD received a $165 million federal grant with a local match of $55 million, he said.

Home buyout funds were also included in the HCFCD’s $2.5 billion bond Harris County voters approved in August 2018. It allocated $46.8 million in local money for buyouts in the Cypress Creek watershed to help secure another $140.5 million in federal grants.

Of the 4,000 or so county residents who volunteered for buyouts following Harvey, only about 1,100 were eligible for a buyout, Wade said. Since Harvey, the HCFCD has purchased 106 homes in the Cypress Creek watershed, where at least 8,750 homes flooded during the storm.

Wade said by the time the HCFCD had secured funding after Harvey, about 30% of the 1,100 homeowners whose applications had been approved for buyouts had already renovated with flood insurance money or sold their homes to investors.

“A lot of investors come knocking at their doors, and they’ve got money in their pocket, and they’re ready to close right then,” he said. “Those investors are counting on desperate owners who want to get out of there, so the investors can pick it up for pennies on the dollar and make money off of it. That’s what we’re competing against. ... A lot of people don’t have the luxury of waiting.”

A lengthy process

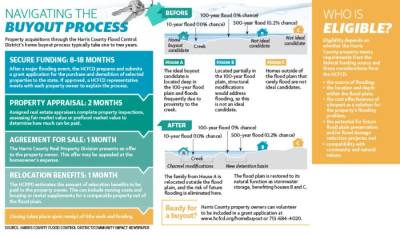

According to HCFCD officials, the home buyout process can play out years after a disastrous flood.

Wade said it only takes about four months to process the appraisal, negotiate the sale, pay out relocation costs and finalize the closing. However, before any of that can happen, he said securing funding can take up to 18 months.

While the funding programs may vary, homeowners who go through the HCFCD’s home buyout program follow the same basic process.

After a property owner volunteers for a buyout, district officials determine eligibility by considering factors such as the source of the property’s flooding, its location and depth within the flood plain, the cost effectiveness of the buyout as a solution, and the potential for future preservation or flood mitigation projects.

Once eligible properties are identified and funding is secured, a real estate appraiser assesses the property’s preflood market value and presents an offer to the homeowner.

Dick Smith, the president of the Cypress Creek Flood Control Coalition, said he sold his home to the HCFCD after it flooded six times between 1982 and 2017, despite being elevated specifically to limit the risk of flooding.

“After Harvey, we decided it was time to bite the bullet,” he said.

Smith volunteered his home for a buyout shortly after Harvey and moved into a new home in July 2018. He said the biggest challenge was that his home had to be vacant upon closing.

“I had retired in 1996, so I had been on a fixed pension for 20-some years, and costs were going up this whole time, [and] we were having a financial crisis,” he said. “So I couldn’t go out and just buy another house [without the buyout funding].”

Finding recovery solutions

Local legislators, nonprofits and other entities are making efforts to supplement HCFCD’s buyout progress.

U.S. Rep. Lizzie Fletcher, D-Houston, said constituents whose homes have repeatedly flooded and local government officials seeking federal funding have consistent frustrations about how long it takes to receive assistance.

Through conversations with the HCFCD, Fletcher said she learned about obstacles to securing disaster mitigation funding from FEMA that often delay needed recovery work. Legislation she proposed would allow certain mitigation projects, including land acquisition for home buyouts, to begin immediately following a disaster without the risk of losing potential FEMA funds.

The Hazard Eligibility and Local Projects Act passed in the U.S. House in December and has been referred to the Senate’s Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs as of press time.

“A lot of what I’ve seen ... is that there are a lot of unintended consequences from the way that legislation is written or the way that certain rules are then implemented,” she said. “But here with something like buyouts ... it’s a real impediment for [homeowners] making a choice to move forward, [and] it’s an impediment for communities not to be able to go ahead with projects like buyouts.”

Three years after Harvey, recovery work is ongoing for families who did not have flood insurance and were ineligible for buyouts. Volunteers from local churches are still helping rebuild homes along Cypress Creek through Cypress-based nonprofit Hope Disaster Recovery, Executive Director Godfrey Hubert said.

“For the most part, there are not many people who are still thinking about Harvey, but we’re still mucking and gutting homes from Harvey,” he said. “There’s still homes in Cy-Fair that are not rebuilt. They’re still gutted. When you drive past them, you can’t tell, but you go inside of them, and their sheetrock is still cut.”

Hope Disaster Recovery’s case managers find resources to help families in flood-damaged homes who could not afford flood insurance or who received FEMA funding for repairs but had to make tough decisions with renovation money.

The nonprofit has invested nearly $13 million in unmet needs assistance for underserved populations since Harvey, Hubert said. Additionally, the group has done $2 million worth of home repairs, having rebuilt 100 homes.

Hubert said for families living in poverty, selling their home and moving is not a feasible option.

“A family that has lived in a house for 90 years, they sell the house and get $40,000-$50,000 to move into an apartment where they have to pay monthly rent,” he said. “Two years later, there’s nothing left. But as long as they own that house, they can live in it for free. It’s not as simple as just selling.”