According to the SBOE, a more thorough evaluation for dyslexia will detect learning disabilities that would have otherwise gone undiagnosed. The proposed amendment was led by SBOE member Audrey Young.

“The committee has taken a huge step to move dyslexia forward and ensure the students are identified early and that they are properly identified for services,” Young said at a Sept. 3 SBOE meeting.

Previously, students suspected of having dyslexia were given a dyslexia-specific evaluation. If the student was dyslexic, they would be protected under Section 504 of the federal Rehabilitation Act of 1973. The Section 504 plan provides a blueprint for how schools support students with disabilities.

The change requires districts to instead test suspected dyslexic students with a special education evaluation, which is conducted through the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

SBOE officials said a benefit to aligning dyslexia with the special education program is students may have the option to receive an individualized education plan. According to the U.S. Department of Education, an IEP is created and monitored by teachers, parents, school administrators and related services personnel to guide special education services.

Local effects

Cy-Fair ISD Chief Academic Officer Linda Macias said this change provides more comprehensive data about students and provides information about needs beyond dyslexia.

“Dyslexia is a neurological and language-based disorder that is remediated through systematic and explicit instruction that rewires the brain to improve the student’s ability to read fluently,” Macias said. “Students with dyslexia are provided services and accommodations based on their individual needs.”

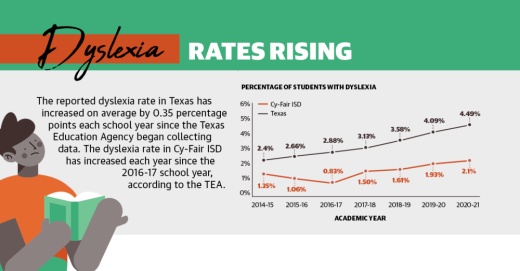

CFISD’s dyslexia rate has grown every year since 2016-17, when 0.83%—or less than 1,000 students—in the district had dyslexia. Macias said the district’s current dyslexia rate is 2.7%, or more than 3,000 students.

She attributes the increase to early screening and staff awareness of dyslexia. Kindergarten and first-grade students are required to be screened for dyslexia, a process that lets educators know whether a dyslexia evaluation is needed. Factors such as difficulty with phonics, reading fluency and spelling may be considered at all grade levels, Macias said.

The reported percentage of dyslexic students in Texas is lower than the national dyslexia estimates reported, according to the TEA. Although the precise prevalence of dyslexia in the U.S. has not been determined, according to a 2019 TEA dyslexia report, conservative estimates put the prevalence at 4% with higher estimates reaching 20%.

Macias said she expects to continue to see the district’s dyslexia rate rise as campuses use data and better understand dyslexia characteristics. As of January, 241 of CFISD’s teachers served as dyslexia interventionists, who receive intense training and deliver multisensory instruction.

“The most common misconception is that the students with dyslexia are not smart and will not be successful,” she said. “Our students have proved this misconception to be incorrect.”