The Department of Equity and Economic Opportunity is the culmination of two years of research, community input and stakeholder meetings, said Sasha Legette, a member of the Harris County Precinct 1 policy team that played an instrumental role in getting the project off the ground.

In the long term, officials said they hope to develop policies and programs that help business owners, individual workers and job seekers, officials said. In its first year, the focus will fall on the county’s own contracting process.

“Sometimes it feels the county is more passive than proactive,” Legette said. “We’re hoping to see a more proactive engagement and innovative policies and programs to address economic disparities and cure historic disinvestment.”

Two additional studies are also underway this year—one in transportation and one in public health—that are meant to further guide how equity can be incorporated into those areas. The public health study will ultimately yield a strategic plan for the county for how it can better bring health care to underserved communities.

The transportation study, slated to be released this summer, is meant to ensure communities are not overlooked for mobility investments. Tom Ramsey, who took over as Precinct 3 commissioner in January after being elected in November, said the county can do better than it has in the past.

“Why should the roads in one area be a lot worse than the roads in other areas?” he said. “Here’s the answer: It’s a choice. Somebody made the choice that the streets in one neighborhood are worse than the streets in another, and we can do better than that.”

Entrenched discrimination

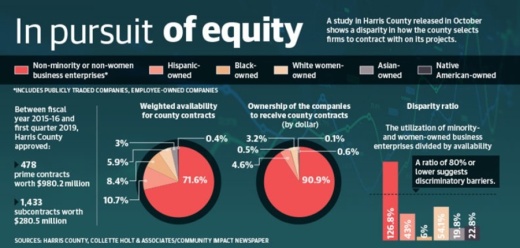

In 2018, the Harris County Commissioners Court approved a study into disparities in the way the county selects firms to contract with on projects. Conducted by the consulting firm Colette Holt & Associates, the study showed the county could be functioning as a passive participant in marketplace discrimination.

The study examined 478 contracts worth about $1.26 billion, including 1,433 subcontracts worth about $280.49 million approved by the county between the 2015-16 fiscal year and the first quarter of 2019. Although roughly 71.6% of business enterprises in the market for county contracts are “non-M/WBEs”—a term that refers to any business that is not owned by a minority or woman—about 90.9% of the county’s contracting dollars went to those firms.

Only 9.1% of county dollars went to minority and women businesses enterprises, including only 0.5% to Black-owned businesses, the study found. The county’s dealings with non-M/WBEs yielded a disparity ratio—which measures the use of businesses divided by their availability—of 32%, according to the study. Any ratio below 80% can be evidence of discrimination, lead researcher Colette Holt said.

“A very lower ratio suggests entrenched discriminatory barriers,” Holt said in an October presentation. “Thirty-two percent is very, very low.”

One of the stakeholders to offer input during the planning process was the Texas Gulf Coast AFLCIO.

Linda Morales, an organizing coordinator with the group, said she was excited to see equity placed at the center of economic development for labor, which she said would ideally connect vulnerable groups to jobs that offer livable wages and growth opportunities. The COVID-19 pandemic made the disparities within the county even more acute, she said.

“With COVID, communities of color have been hit hard,” she said. “We want to make sure these communities are prospects for upward mobility, for some good jobs and jobs that might have training programs.”

An estimated 84 disadvantaged business enterprises, 172 minority business enterprises and 94 women business enterprises are in operation across the seven ZIP codes that make up the Cy-Fair area: 77040, 77064, 77065, 77070, 77095, 77429 and 77433.

The data, which comes from a directory maintained by the city of Houston, includes firms that could stand to benefit from the new county initiative, including construction, engineering and consulting.

The woman-owned traffic and transportation engineering firm Stevens Technical is among them. Headquartered on FM 529, it was founded in 2010 by Roma and Charles Stevens.

Charles, who serves as principal and CEO, said the firm has met with Ramsey, who encouraged them to have all their paperwork in order.

“I think it will be a positive for my engineering firm,” he said. “We’re excited about it.”

Stevens Technical has worked with Harris County on contracts in the past, and also has prime contracts with the Texas Department of Transportation, Charles said. With the new program in place, he said his firm will get more of a chance to show its expertise. He said he expects talent to prevail in the county’s decision-making process.

“They want to work with people who know what they’re doing,” he said.

Years in the making

The Harris County Commissioners Court first ordered the new department to be created in January 2019. The office will be headed by Pamela Chan, who was appointed in November.

From that time on, officials hosted meetings with community members and studied similar departments in other cities, Legette said.

In its first year, department leaders said they expect to focus on relationship development with communities, local businesses and M/W/DBEs. In the longer term, work could expand to include bringing more economic opportunity to individual workers, entrepreneurs and job seekers in underserved areas.

“In a county as big as Harris, things vary from region to region and from precinct to precinct,” Legette said. “The priorities and the needs are probably going to look a little different.”

Morales said it will be crucial for the new office to set clear goals and be transparent with the public in how well it meets those goals.

“You have to have the proof in the pudding,” she said. “So many things have been done in the past that sounded pretty, but there was no result. We want to see results with this.”

Economic health, physical health

Efforts to improve economic opportunity in disadvantaged communities can have direct effects on physical health as well, said Heidi McPherson, the senior community health director with the American Heart Association in Houston.

The AHA branch worked closely with the Precinct 1 office in setting the groundwork for the launch of the new department. Any work that involves raising incomes and promoting career development is aligned with the AHA mission of ending chronic disease, she said.

“We know that if you can develop the capacity to be productive, people will have better jobs,” she said. “Better jobs have better access to health care. All of these things then align and point towards improved health and life expectancy.”

McPherson, who also co-leads the Greater Houston Coalition on the Social Determinants of Health, said she expects to see the conversation on equity in health care become even more of a focus in 2021, with more than 120 organizations working toward systemic solutions.

“We’re doing that by addressing the social drivers of health outcomes,” she said. “When you break that down, that’s things like nutritional security, housing security. At the root of those is income and poverty.”

Life expectancy rates across Harris County vary widely, with more socially vulnerable areas in east Houston in the 65-69 range and wealthier areas such as River Oaks in the 80-90 range, according to a 2020 study released by the Harris County Public Health Department.

The disparities exist in Cy-Fair as well but are less pronounced. The outer ranges of Cy-Fair, where social vulnerability is lower, have a life expectancy range between 80-84, while the areas around FM 1960 and Willowbrook range from 70-79.

In a January budget hearing, Dr. Esmaeil Porsa, the CEO of the Harris Health System, said an update on that report will be provided to Harris County commissioners in March. The county is looking into how to expand services in high-need areas, he said.

“The emphasis is really going to be on taking the care to the community,” he said. “Part of that is looking at our community clinic infrastructure. Are we in the right places? Are there opportunities in some of the geographies where we should be but currently are not?”

Part of the challenge is that each community has different needs, McPherson said. A community’s needs can range from the need for healthy food to access to purified drinking water in schools to access to hike and bike trails.

“The need is great, [but] the opportunity is great,” she said. “It feels like collectively across the Greater Houston area, we really do have the opportunity to lead the nation.”