Both of her children are completing schoolwork from the family’s home in Copperfield, so Carr is spending more money on utilities and food. She said she has relied in part on an organization called Cy-Fair Helping Hands to put food on the table.

“That was huge for me,” she said. “I’ve had all the kids here, so all of my utilities are doubled—the light bill, the water bill, the grocery bill. Getting that extra help is wonderful.”

The Texas Workforce Commission reported nearly 12% of Cy-Fair’s population has filed for unemployment benefits since mid-March.

Nicole Lander, the chief impact officer at the Houston Food Bank, said higher unemployment rates have driven an increase in food insecurity—a term defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture as a lack of consistent access to enough food for a healthy life. According to statewide hunger-relief organization Feeding Texas, 14.8% of Harris County’s overall population and 21.2% of its children were considered food insecure in 2018. Due to the pandemic, those numbers in 2020 are estimated to be 20.1% and 30.4%, respectively.

Lander said the Cy-Fair area already had many families living on less than what is considered a livable wage, and the area was the first regionally to see food distribution efforts surge this spring.

“Anecdotally what we would hear ... is both people in the house lost their job instead of just one,” Lander said. “So, it might be a brand-new SUV driving in, but they were good wage earners and now have burned through their savings and need food assistance.”

Financial strains

Feeding Texas CEO Celia Cole said food insecurity is directly related to economic insecurity.

"For some, that means an intermittent bout of hunger toward the end of the month when funds are low,” Cole said. “For others, it’s a constant state of hunger and reduced access to food.”

At Cypress Assistance Ministries, Director of Development Janet Ryan said apart from the coronavirus crisis, the number of people needing assistance increases every year. This includes the percentage of Cy-Fair ISD students qualifying for free and reduced-price meals, which was 54.2% in 2019-20.

Lander said she believes the food bank has not yet seen its peak of pandemic-related need due to continuous layoffs and potential evictions that could result in an uptick in homelessness.

In addition to skyrocketing unemployment rates and wage losses, the cost of everyday grocery items has also gone up this year. According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, meat prices nationally have grown 12.3%, and the prices of fresh fruits and vegetables increased by 3.3% from January to June.

“The current situation that has left so many people needing help truly is not one that anyone could have projected or planned for, and people are really trying hard,” Ryan said.

Effects of food insecurity

A poor diet is a common consequence of food insecurity. Lander said many clients at the food bank deal with Type 2 diabetes, heart disease and obesity. When people do not know where their next meal is coming from, they tend to choose high-calorie, high-fat items to feel satiated, and an infrequency of meals also causes the body to store fat, she said.

“COVID-19 definitely showed most people weren’t cooking at home—it’s so much easier to drive through and grab something at a low amount of money for a household that’s already struggling than to go to the store and buy a complete meal with fruits, veggies and grains,” Lander said.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, food-insecure adults in Harris County are likely to spend $2,205 more annually on health care than their food-secure neighbors.

Officials said children in particular who face food insecurity often struggle academically and with feelings of isolation. About 1 in 5 children in the Houston Food Bank’s service area

came from food-insecure households before the pandemic, Lander said.

came from food-insecure households before the pandemic, Lander said.The food bank has partnered with local nonprofit Cy-Hope since 2011 to send students home with food over the weekend. Executive Director Lynda Zelenka said these children would otherwise go hungry without access to school breakfasts and lunches.

"When you think about being a child and your stomach’s growling, your focus is on, ‘Where’s my next meal going to come from?’” Zelenka said. “When they feel secure about being fed, ... that gives them the sustenance to focus on their schoolwork and to focus on other things.”

CFISD distributed more than 1 million free curbside meals for students while campuses were closed this spring and summer. Officials are partnering with the USDA to continue offering free on-campus and curbside meals to all students regardless of financial need through the end of 2020.

Nonprofits step up

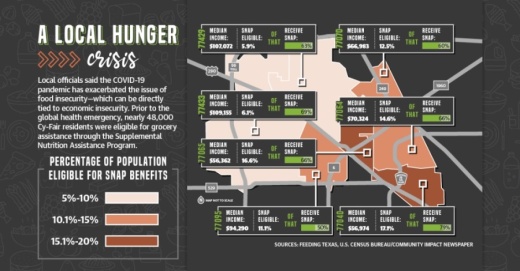

Federal programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program can help offset the cost of groceries for low-income families. But according to Feeding Texas, the program covers only about $1.26 of the $2.66 it costs to purchase a nutritious meal at the average Cy-Fair grocery store. Community organizations can help families fill the gap.

Cy-Hope has helped host 26 distribution events in recent months. Zelenka said 105,000 households were given more than 6 million pounds of food.

Cypress Assistance Ministries fed about 67% more people from March to September than it would in a typical year, Ryan said.

Patricia Hudson, the executive director of community outreach for Cy-Fair Helping Hands, said the number of families frequenting its food pantry has tripled since early 2020. Individuals come from a range of ages, income levels and ethnic backgrounds, but many are recently unemployed.

“The phone is ringing constantly with people asking for help, and it’s gone from just food to, ‘Can you help pay our bills?’” Hudson said.

At the same time that need is increasing, the number of volunteers is on the decline.

“We need businesses, organizations and churches to hold food drives, people to volunteer and to write checks,” Ryan said. “We’re coming up on the holidays, and there’s always an increase in [need].”