The policy approved in August required educators to categorize many of the district’s 1.5 million library books plus the books available in over 13,000 classrooms, so the board approved a Jan. 17 implementation date.

These updates come at a time when some vocal community members claim they believe CFISD is providing obscene reading materials. However, district policy states libraries cannot offer “obscene” or “harmful” material as defined by the Texas Penal Code.

“A lot of folks are concerned. They’ve become aware that there’s books in the library that have content that they find objectionable and don’t want their kids exposed to,” state Rep. Tom Oliverson, R-Cypress, said. “A lot of it is what I would label as hypersexual or borderline pornographic or maybe just outright pornographic. And the question is: How do we deal with that?”

Oliverson and other lawmakers are pushing for library content regulation with several bills already filed in the 88th Texas Legislature.

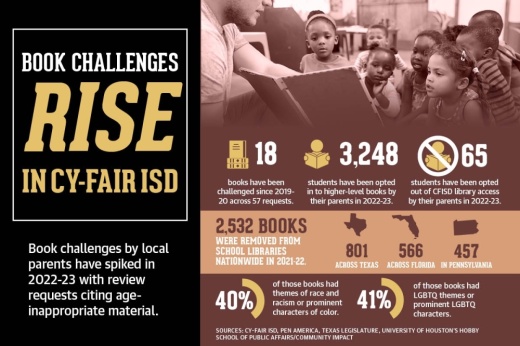

Since 2019-20, CFISD parents have formally challenged 18 unique titles across 57 requests—51 of which were filed in 2022-23. District policy states library materials should be varied in difficulty levels, have diverse appeal and showcase different viewpoints. Education policy experts said while it is important for educators and parents to consider age-appropriateness, they believe removing books so no student has access to them is not beneficial.

“I think the way that you avoid raising a myopic, small-minded generation of kids is by giving them the space to learn about the world, learn about different ways of being, different ways of thinking and to come to their own conclusions,” said Blake Heller, assistant professor in the Hobby School of Public Affairs at the University of Houston.

District policies

All library books in CFISD are categorized into three collections—juvenile, young adult and adult. By default, all students have access to the juvenile collection, and students in grades 7-12 have access to the young adult collection.

Parents may have the option to grant their children access to a higher-level reading collection.

According to district data, parents have opted to give 3,248 students access to higher-level collections, and 65 students had been opted out of library access altogether as of Feb. 3.

While educators can assist students in the book selection process, students and parents have the final say on whether books are appropriate for them, district policy states.

Parents can see what books their children have access to through the online library catalog.

“It’s been real popular lately to talk about parents’ rights, but a lot of times when parents are talking about parents’ rights, they’re only talking about their rights. They’re not talking about other people’s rights,” Superintendent Mark Henry said at a Nov. 10 board work session. “And I think we’ve set up a system where all parents have a right to help dictate what their children can read.”

Parents can also challenge individual titles at any campus. A committee consisting of at least a campus or district administrator, librarian, instructional staff member and Campus Performance Objective Committee parent must read each challenged book and determine within 30 days whether it meets policy.

Of the 12 titles challenged this school year, many were in this review process as of press time. Only one was removed from collections at two high school campuses: “Fun Home,” by Alison Bechdel.

The 2006 illustrated memoir addresses themes of sexual orientation, family relationships and suicide.

Additionally, Community Impact reported in mid-2022 that the district had removed nine books that were brought to its attention by other districts or included in a list of 850 books state Rep. Matt Krause, R-Fort Worth, said in an October 2021 letter could cause students to feel “psychological distress” because of their race or sex.

Book challenges

CFISD parent Tana Lam spoke about the reconsideration committee process at the Jan. 12 board meeting, saying the time-consuming task adds stress to district educators. She said five people submitted a “crazy amount” of formal book challenges in the prior weeks—28 of which were by Trustee Lucas Scanlon’s wife, Bethany.

“These book reviews can be pushed up the chain until they get to the board level to make the final determination, so we could have Trustee Scanlon voting on the books [his wife] disapproves of. How is that not a conflict of interest?” Lam said.

Bethany Scanlon declined an interview for this story.

Margaret Hale, the curriculum and instruction department chair for the University of Houston’s College of Education, said book challenges have trended upward over time. Parents in today’s political climate feel empowered to make judgment calls about books, she said.

“I think that people are possibly engaging in this practice in an effort to shelter their own children from issues they feel are going to sway their children’s thinking, but they’re not taking into consideration that there may be other children who need to see these kinds of books,” Hale said.

Hale said while some parents may not want their children exposed to LGBTQ stories, for example, there are students in the LGBTQ community who benefit from seeing themselves represented in literature. Non-LGBTQ students can also benefit from learning about people who are not like them, she said.

A report from PEN America, a national nonprofit that promotes free expression through the advancement of literature, found Texas public school libraries banned more books than any other state in 2021-22, and most books challenged across the U.S. that year featured either LGBTQ themes and characters or themes of race with characters of color.

Legislation filed

Oliverson said he believes the book access issue has gained new traction recently because the COVID-19 pandemic gave parents a closer look at what was being taught in schools.

“It was not just simple reading, writing and arithmetic, and so I think that prompted a broader conversation about what is really going on in the classroom,” Oliverson said.

Library legislation followed the passage of House Bill 3979—the “critical race theory” bill—in 2021, he said, which limited the way educators can teach about race and current events.

Several bills about school libraries have been filed this session, including House Bill 338, filed by Oliverson, which would require book publishers to post content ratings on all books sold to public schools.

“It shouldn’t be a surprise when your 8-year-old checks [a book] out from the library and there’s illustrations of explicit sexual acts or stories of rape or violence or masturbation or other things—none of that should come as a shock to a child, a parent, a teacher, a librarian, an administrator,” Oliverson said.

CFISD officials said categorizing books into collection levels was a challenge because many books in their system did not already include this information.

A survey conducted in January found 71% of Texans support this concept of requiring publishers to include content ratings in books sold to public schools, according to a report from the Hobby School of Public Affairs at the University of Houston.

Heller said content ratings have been successful in other media such as movies, music and video games, and they could be useful resources for parents, librarians and teachers.

“I think these rating systems are part of finding a middle ground where we’re not just arbitrarily banning anything that offends our personal sensibilities,” Heller said. “But at the same time, it gives teachers ... an impartial third party backing them up—‘Hey, I know you might not love the themes in this book, but it’s rated for 14-year-olds, and the kids are 15.’”