From January 2019 to September 2021, opioid overdose deaths in Texas nearly doubled, the National Center for Health Statistics reported—from 1,470 to 2,561. The troubling trend followed national numbers, as the NCHS reported a 30% increase in nationwide opioid deaths from 2019 to 2020 and a rise in the drug overdose death rate per 100,000 people from 21.7 to 28.3.

In 1999, when the NCHS first collected data, 16,849 drug overdose deaths were recorded with a death rate of 6.1 per 100,000 people. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, pharmaceutical companies began marketing prescription opioid pain relievers as drugs that were not as addictive as previously thought in the late 1990s. As a result, these drugs, which had formerly only been prescribed to treat acute pain, became the prescription of choice to treat chronic, long-term pain.

Tyler Varisco, a health services researcher with the University of Houston, described several underlying causes of substance use disorders that the pandemic exacerbated, including patient access to treatment, increased financial stresses and isolation.

“These are diseases of despair that we’re dealing with,” Varisco said. “When people are economically challenged or psychologically challenged as many of us have been over the past two years, we see increased vulnerability in our communities to opioid use and other forms of substance misuse.”

To address the opioid crisis, the state has invested over $200 million since 2017 into the Texas Targeted Opioid Response, a program directing Texans to resources for treatment, opioid disposal, and education on opioid use disorders and prescriptions. Meanwhile, local municipalities, such as Conroe and Willis, are also set to receive funds from a $1.89 billion settlement with drug manufacturers won by the state, while emergency responders have implemented programs to help fight the epidemic.

Telehealth affecting treatment

With in-person treatment at risk due to the coronavirus, health care centers went remote in 2020. Katy Franklin, a substance use disorder counselor at Tri-County Behavioral Healthcare, said the transition was difficult for patients. A federally qualified health care organization, Tri-County’s substance use disorder program serves 13 counties, including Harris and Montgomery counties.

“It’s not the same level of care; you’re missing some things over Zoom that you wouldn’t in person,” Franklin said. “Treatment was less effective for this particular population.”

Varisco said he believes the drastic changes to health care for individuals experiencing addiction undid the positive work done for patients before the pandemic.

According to the Treatment Episode Data Set, which compiles national patient discharges from treatment for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, detoxification treatment discharges became less common from 2016-19, when detoxification discharges decreased from 20% of all discharges to 16%.

“When you have a destabilizing event like a global pandemic, [vulnerabilities in health structures] become more evident,” Varisco said.

At the beginning of the pandemic, Varisco said there was “some confusion” about what treatments were acceptable to prescribe. A 2020 memo from Phil Wilson, the Texas Health and Human Services executive commissioner, said buprenorphine could be prescribed virtually, but methadone required a face-to-face evaluation before the first dose could be provided.

According to the SAMHSA, buprenorphine and methadone are Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs used to treat opioid use disorders.

“I don’t know if [the policy] was well understood by providers, and that led to lapses in our treatment,” Varisco said.

Prescription problems

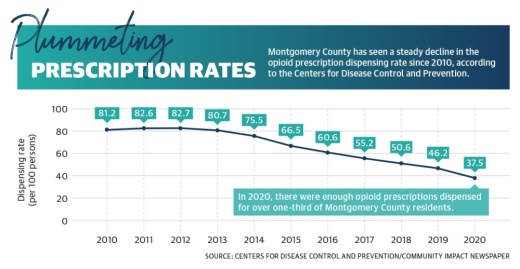

Varisco, who trained as a pharmacist at The University of Texas, said unnecessary prescriptions and overprescriptions have yet to be addressed for pharmacy students. In 2020, a little more than one prescription was issued on average for every three residents in Montgomery County, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. However, the dispensing rate has been cut in half since 2014, and from 2019-20, it declined 19%.

“This crisis has exposed cracks in the system and made them a lot more evident,” Varisco said. “We’ve known we have had problems with training prescribers and preventing unnecessary prescriptions.”

Varisco also highlighted a lack of providers for treatment drugs such as buprenorphine in lower-income areas in the state. The SAMHSA’s buprenorphine provider map showed in the Conroe-Montgomery area, there are no approved providers in the Montgomery or Willis area, although there are 10 in Conroe.

Tiffany Young, a spokesperson for the Texas Health and Human Services Commission, said following the launch of the TTOR in 2017, over three-quarters of the state are within 30 minutes of a medication-assisted treatment.

“We have seen an increase in access and use of telehealth services by individuals that did not previously have access to these programs,” Young said.

However, a public TTOR map showed parts of Montgomery County north of The Woodlands do not have a state-operated treatment site within a 30-minute drive.

Other commonly abused substances do not have treatments readily available either. Jane Maxwell, professor emeritus at the University of Texas, said cocaine and methamphetamine are two commonly abused substances that do not have treatment beyond abstinence or quitting the drug outright.

Some barriers for treatment go beyond drug-related issues, such as the lack of accessible public transportation in Texas.

“Proximity to care is just not there. Patients are in rural areas, but providers are in the cities,” Varisco said.

Government solutions

Federal, state and local entities are working to address the opioid epidemic through funding, law enforcement resources and increased education surrounding opioid misuse.

James Campbell, chief of emergency medical services for the Montgomery County Hospital District, said law enforcement initiatives, including the use of naloxone—an overdose emergency treatment—were implemented in 2019 to prevent opioid overdoses in Montgomery County.

“We train and educate law enforcement on how to use Narcan [device that delivers naloxone],” Campbell said. “When they arrive to a patient who’s not breathing from an overdose, they’re able to give the Narcan before the ambulance even arrives.”

In addition, the TTOR has received over $280 million in funding since its inception in 2017, Young said. The TTOR offers programs for Texans to discard unneeded opioids as well as video trainings for health professionals to limit unnecessary prescriptions.

Statewide, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton announced Feb. 16 that the state secured a nearly $1.17 billion settlement with three major pharmaceutical companies: AmerisourceBergen, McKesson and Cardinal. According to the attorney general’s announcement, Texas has secured $1.89 billion to date from opioid settlements.

“Texans have been devastated by the opioid crisis, and it is important that this settlement is proportioned fairly among the communities that need it most,” Paxton said in a statement.

The cities of Conroe, Montgomery and Willis joined more than 400 other Texas municipalities that have signed on to receive funds from settlement agreements with Janssen, owned by Johnson & Johnson; AmerisourceBergen; Cardinal Health; and McKesson.

According to global settlement allocation figures from the Texas Attorney General’s Office, Conroe will receive $466,671; Willis will receive $24,384; Montgomery will receive $1,884; and Montgomery County will receive $2.7 million.

Varisco said he would like to see settlement money flowing toward poorer and rural communities to help address the disparity in treatment options those communities face. Franklin agreed, adding a state- or federally funded detoxification center could ease capacity and make treatment more affordable.

“Private detox and residential treatment on the cheap end [is] $20,000,” Franklin said. “[A state-funded center] would also increase capacity. You have such a small window for someone to seek treatment, and you need to capitalize on that before they relapse.”

Ally Bolender contributed to this report.