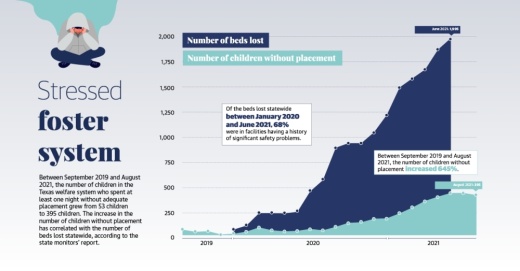

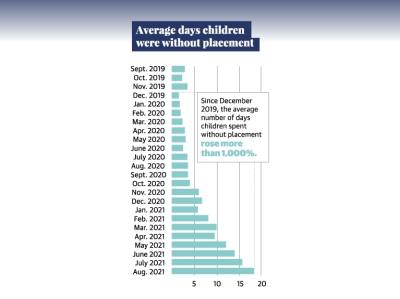

Further, the number of children who experienced at least one night without proper placement increased more than seven times from 53 children to 395 children between September 2019 and August 2021, DFPS data shows.

Child Protective Services is responsible for selecting an adequate placement when the DFPS takes temporary or permanent custody of a child. If a placement is not found, such as with kin or a foster family, the DFPS becomes the direct provider of services.

These children are often placed in hotels or DFPS offices, rather than foster homes or residential treatment centers. In September, a report by court-appointed monitors inspecting Texas’ foster system found placing children in these settings poses substantial risks to their safety because these placements lack regulations and resources available to children in adequate placements.

“[Being without a placement] is not ideal for any child ... because those needs that must be met, I don’t see how they are being met,” said Patricia Johnson, who worked for 27 years for the DFPS and is the kinship director for Angel Reach, a nonprofit serving youth who have aged out of the foster system in Montgomery County.

Factors contributing to the rise in children without placement, or CWOP, include the loss of hundreds of beds in foster care facilities stemming from closures due to heightened monitoring, which subjects these facilities to stricter guidelines, DFPS’ report said.

Locally, Montgomery County organizations have stepped up to try to alleviate the issue.

“Montgomery County is really blessed with organizations that really want to stand beside and shepherd and grow programs for children in foster care,” said Catherine Shultz, executive director of Love Fosters Hope, a Montgomery County nonprofit that provides resources for foster youth.

Increased scrutiny

In November 2018, the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals established “heightened monitoring” of Texas’ child welfare operations. The practice was born out of ongoing litigation since March 2011, alleging the state had multiple constitutional violations in how it runs its child welfare system.

As part of heightened monitoring, child welfare facilities that contract with the state and have a history of policy violations are subject to increased inspections and corrective actions, according to the 2018 ruling. Facilities that do not comply with heightened monitoring could no longer receive new foster youth or face fines, revoked licenses or contract termination.

Texas lost 2,129 beds in general residential facilities between January 2020 and September 2021 due to heightened monitoring, according to the court monitors’ September report.

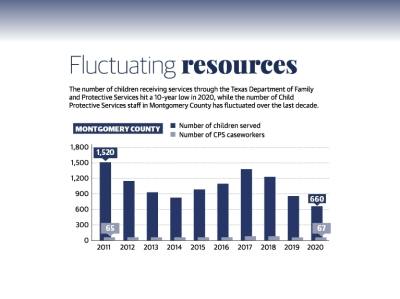

To meet growing demands on the welfare system in the state, the DFPS has identified a need for 669 additional beds and 236 caseworkers, according to the DFPS September report. ••In Montgomery County, there were 67 CPS caseworkers in 2020, an increase of four from the previous year, although the number of children served increased by nearly 400 to 1,520, the DFPS reported.

Multiple pieces of state legislation passed in 2021 sought to address these shortages.

Senate Bill 1896 revised and added rules and regulations for the DFPS, including forbidding the department from housing a child in an office overnight and expanding eligibility for therapeutic foster care.

SB 1 also provided an additional $83.1 million to hire 312 caseworkers, according to the DFPS’ September report. House Bill 5 allotted another $90 million to the DFPS to retain providers and increase capacity to serve foster youth, according to the bill.

“The importance of this funding cannot be overstated,” said Melissa Lanford, the media specialist for DFPS Region 6, which includes the Greater Houston area. “It is the difference between a real placement for these older children and continuing to live in a CPS office or hotel.”

CWOP crisis

In addition to fewer beds in foster facilities and a shortage of caseworkers, the DFPS September report stated heightened monitoring has played a role in the crisis as it has led to the loss of hundreds of beds within the state, including locally.

The Tree House Center, a general residential facility in Conroe with 25 beds, was placed on heightened monitoring and had its license revoked in May due to safety violations, the court monitors’ report said.

Johnson said she believes new policies to keep children safe have instead had an adverse effect. She said additional beds need to be planned to anticipate operations closing.

“For every home that is closed, you almost need two more to open,” Johnson said.

Not only is there a need for more beds, but there is also a demand for services for children with higher acuity needs, the court monitors’ report said. Sixty-six percent of CWOP require specialized or intense care, compared to 20% of all children, the report found.

The report found as the number of CWOP increased, serious incidents involving these children, such as mental health episodes, physical aggression toward staff and self-harm, also increased. In January, there were seven such incidents involving CWOP, while in June there were 69 incidents.

“Being removed from your home is one of the most traumatic things that a child can endure, and then going the next step and being a child without placement is even more traumatic,” said Ann Marie Ronsman, executive director of Court Appointed Child Advocates of Montgomery County.

Local efforts

Many child welfare organizations in Montgomery County have tried to address the rise in CWOP, nonprofit leaders said. While organizations such as CASA of Montgomery County are not able to place children, CASA moved into a new property in Conroe at 505 N. Main St. on Nov. 15, Ronsman said, which will provide additional classes and connections for CWOP, something the organization could not do before.

Additionally, local partners, such as CASA, County Judge Mark Keough and the district attorney’s office, held the inaugural meeting Sept. 10 of the Montgomery County Trauma Informed Task Force, of which Ronsman is a co-chair. Ronsman said the group will focus on educating the community about childhood trauma.

“The more that we can all understand how to work with kids, the better those kids will do,” Ronsman said. “Sometimes that isn’t intuitive with children with trauma, so that’s what we’re trying to do with community education.”