Updated April 18: This article has been corrected to say that Webb Melder is the former president of the LGSCD elected board.

Editor’s note: This is part two of a series examining groundwater regulation in Montgomery County. Part one can be found here.

Private property rights are at the center of a debate waging over groundwater regulations in Montgomery County, and recent regulatory decisions have highlighted differences in opinion on how groundwater should be managed.

On April 9, Groundwater Management Area 14—which includes the Lone Star Groundwater Conservation District, the entity that regulates Montgomery County’s groundwater, and four other districts—voted on its proposed long-term goal for the Gulf Coast Aquifer System. The goal, known as a desired future condition, or DFC, establishes how much groundwater districts within GMA 14 can pump.

The proposed DFC includes a subsidence factor, meaning districts must restrict their pumpage to allow for less than 1 foot of additional average subsidence, or sinking of the earth, between 2009 and 2080. LSGCD was the sole entity opposed to this metric requirement, advocating instead for the DFC to consider metrics applicable to each district based on best available science.

“The district is advocating for DFC statements that accurately represent the aquifer conditions and geology and for using metrics that are applicable to the districts based on their varying aquifer conditions,” LSGCD General Manager Samantha Reiter said in an email.

LSGCD officials have said protecting property rights is their No. 1 factor when making regulatory decisions. According to Texas law, landowners own the water underneath their property, and groundwater conservation districts must ensure regulations do not infringe on an entity’s or individual’s right to pump groundwater.

“[That] is really the No. 1 goal,” LSGCD President Harry Hardman said. “That’s how we are going to be managing moving forward.”

Groundwater—cheaper than surface water, which is largely supplied from Lake Conroe—is critical for entities such as the city of Conroe, City Council Member Duke Coon said. After LSGCD lifted its prior pumping restrictions in September, Conroe requested an additional 500 million gallons of groundwater to its annual pumping permit.

But in areas farther south such as The Woodlands, residents worry excessive groundwater pumping may be causing subsidence, or the gradual sinking of the earth, which can lead to flooding and infrastructure damages. Some areas in The Woodlands have recorded a subsidence rate of just over 1 centimeter per year, according to data from the Harris-Galveston Subsidence District. Northern parts of the county have also experienced subsidence to a lesser extent.

“Property rights to me means the right to have my property kept sound and not have my foundation crack or my house subjected to flooding,” The Woodlands resident Carolyn Newman said.

Groundwater conservation districts must walk a tightrope protecting individuals’ right to pump groundwater as well as the rights of those affected by others’ pumping, said Gregory Ellis, an attorney who represents Texas groundwater conservation districts and subsidence districts.

“You’re really always talking about property rights versus property rights,” Ellis said. “You have the property rights of the person who has the well ... [and] you have the property rights of the people who want to keep their land above sea level.”

Changing priorities

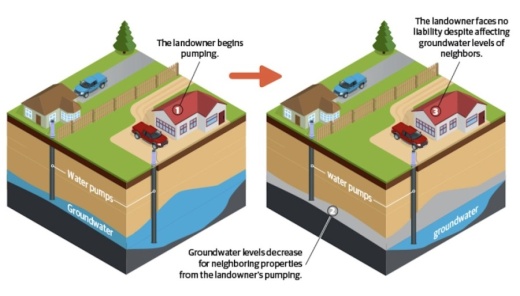

Texas’ Rule of Capture, adopted in 1904, allows landowners to pump as much groundwater as they choose without liability, regardless if that dries up a neighbor’s well. Texas is one of the few states to follow this rule, although there are exceptions to it, such as if the landowner is pumping maliciously, Ellis said.

For example, the 1999 Ozarka Case centered around a well owner who said his neighbor’s pumping had dried up his well, but the Texas Supreme Court reaffirmed the Rule of Capture. In Edwards Aquifer Authority v. Day, the Texas Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that landowners have a vested interest in the groundwater beneath their property and that regulations that go too far in limiting pumping could result in liability.

Groundwater conservation districts were created by the Texas Legislature in 1949 to regulate groundwater, and they issue pumping permits to local entities, such as the cities of Conroe and Montgomery.

LSGCD has faced its own share of lawsuits. In 2015, the city of Conroe and seven other stakeholders filed a lawsuit against LSGCD over the district’s groundwater rules that restricted large-volume groundwater users. At the time, LSGCD was governed by an appointed board whose long-term management plan centered around groundwater sustainability.

“[The] rationale behind that litigation was based upon the fact that the management standard was too restrictive and violated private property rights by not allowing people to pump enough groundwater and that the rules were statutorily invalid,” LSGCD general counsel Stacey Reese said.

A judge ruled in 2018 that LSGCD had no authority to enforce the rules and said they were invalid; however, he did not make a decision on whether the rules violated private property rights. Rather, he recommended this be taken to an appellate court.

LSGCD appealed, but before the case was heard by an appellate court, a significant shift occurred: LSGCD’s appointed board was replaced under the Legislature by an elected board primarily focused on protecting private property rights. The new board fired its legal counsel and settled the lawsuit, and the appeal was dismissed.

All seven of the newly elected board members were endorsed by Simon Sequeria, the president of Quadvest, a utility company based in Magnolia that was also part of the lawsuit. Sequeria launched nonprofit advocacy group Restore Affordable Water in early 2018 to campaign for new board members.

Webb Melder, former Conroe mayor and former president of the elected LSGCD board, said the priorities shifted under the new board to “property-based” regulations.

“Private property rights means a regulatory structure that provides each owner of groundwater the right to access their fair share,” he said. “The new elected board changed their regulations to be lawful.”

Under the elected board, LSGCD is prioritizing protecting private property rights in its regulatory decisions. Groundwater conservation districts are required to consider nine factors such as private property rights, socioeconomic impacts and subsidence when proposing a desired future condition. However, the statute does not dictate how much weight each factor should receive.

Different demands

Groundwater withdrawal effects are felt differently across the county, officials said. The rapidly growing city of Conroe cannot afford to have its groundwater production curtailed, Coon said.

“If there’s a limitation on water, that definitely affects development in the future,” he said. “We’re not just talking about homes; we’re talking about schools; we’re talking about industry.”

Meanwhile, The Woodlands residents claim their properties are suffering damages from subsidence and fault line activity, which have both been linked to excessive groundwater withdrawals, although it is not clear if this is a result from pumping in Harris or Montgomery counties.

The Woodlands Township Chair Gordy Bunch claimed the effects of subsidence and fault line activity on a home he owned cost him $1 million in damage, including extensive cracks in the house. Multiple residents also submitted emails urging the LSGCD board to consider the effects of groundwater regulations on their properties.

Hardman said the concerns of a few individuals cannot be the basis for groundwater decisions for the entire county and that The Woodlands can increase its surface water usage to limit subsidence. The Woodlands uses a mix of about 65% groundwater and 35% surface water, officials said.

“The people in The Woodlands have to weigh what’s more important to them: Having a higher water bill and not having subsidence or ... a reasonable amount of subsidence [and] keeping your water bills more affordable,” Hardman said. “That’s the responsibility of the people of The Woodlands to determine, not us.”

Critics of LSGCD’s current management include Jim Stinson, general manager of The Woodlands Water Agency and former LSGCD appointed board member. Stinson questioned whether pumping rights should adversely affect others.

“The current LSGCD board was carefully selected and supported by politically active individuals who place much more emphasis on private property rights than a public and regional water planning strategy,” he said.

Others such as Jace Houston, general manager of the San Jacinto River Authority, an entity that provides surface water, predicted LSGCD’s stance on groundwater management may conflict with the rest of GMA 14’s when it came time to propose a DFC for the region’s aquifer system, which took place April 9.

“Lone Star’s board is going to have to deal with this issue,” he said in an interview with Community Impact Newspaper in December. “All of this is coming to a head.”

Vanessa Holt contributed to this report.