One of those parents, Shannon Vollaro, said her daughter was evaluated for dyslexia in elementary school at CISD but tested negative. Now a high school senior, her daughter continued to struggle until sixth grade, when she was tested again. The district notified her the test recognized her reading disorder, which was a different form of dyslexia, Vollaro said.

Because Texas did not require dyslexia to be tested through special education testing, the test Vollaro’s daughter originally took was not in depth enough to catch her specific reading disorder, Vollaro said.

“[She] had to teach herself to read and write because she was not taught the way she needed to be,” Vollaro said. “She was already behind.”

The Texas State Board of Education unanimously voted Sept. 3 to adopt an amendment to the Texas Education Agency’s Dyslexia Handbook aligning dyslexia testing guidelines with federal guidelines. According to the SBOE, a more thorough evaluation for dyslexia will detect reading disorders or learning disabilities that would have otherwise gone undiagnosed.

“We believe that this change will best help us identify students who meet the qualifications of a student with dyslexia and/or dysgraphia, and, more importantly, we believe that we will also ensure that we are not missing eligibility in any other areas as we move to the [full evaluation] process,” said Cortney Clover, Montgomery ISD’s executive director of specialized learning, in an email.

The proposed amendment was led by SBOE member Audrey Young, who represents District 8, including Montgomery County. Young is the vice chair on the SBOE Committee of Instruction, which is responsible for the education of individuals with disabilities. She also serves on the Special Education Funding Allotment Committee.

"The committee has taken a huge step to move dyslexia forward and ensure the students are identified early and that they are properly identified for services,” Young said during the Sept. 3 SBOE meeting.

According to CISD officials, the district implemented the change at the start of the 2021-22 school year prior to the amendment’s passage.

Changing how Texas tests

Previously, students suspected of having dyslexia were given a dyslexia-specific evaluation. If the student was dyslexic, the student would be protected under Section 504 of the federal Rehabilitation Act of 1973—which includes students who have a physical or mental impairment. According to the TEA, the Section 504 plan provides a blueprint for how schools support students with disabilities.

The change in the handbooks requires districts to instead test suspected dyslexic students with a special education evaluation. The full special education evaluation is conducted through the federal Individual with Disabilities Education Act. According to CISD and state officials, the evaluation is more rigorous and in depth.

SBOE officials said a benefit to aligning dyslexia with the special education program is students may have the option to receive an individualized education plan, or IEP. According to the U.S. Department of Education, an IEP is created and monitored by teachers, parents, school administrators and related services personnel to guide special education services.

Vollaro said her daughter was in the Section 504 program, but if she had been tested through a special education evaluation, her reading disorder would have been caught earlier on, allowing her to receive an IEP.

“She is an amazing advocate for her peers and herself, but she is having a challenging time getting her driver’s license and doing other things that teenagers do,” Vollaro said.

Identifying more students

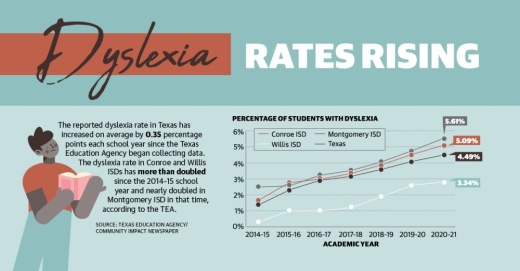

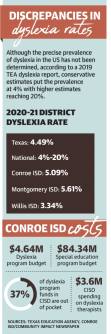

The reported percentage of dyslexic students in Texas is lower than the national dyslexia estimates reported, according to the TEA. Although the precise prevalence of dyslexia in the U.S. has not been determined, according to a 2019 TEA dyslexia report, conservative estimates put the prevalence at 4% with higher estimates reaching 20%. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development estimates the 2019 prevalence of dyslexia at about 10% nationally.

The TEA report said there is a wide range because practitioners use different evaluations for determining dyslexia. TEA data shows the percentage of dyslexic students in Texas increased from 2.4% in 2014-15 to the current estimate of 4.49% in 2020-21.

CISD officials said the 2021-22 district dyslexia rate is 5.3%, and MISD officials said the 2021-22 district rate is 6.6%. Willis ISD did not respond to requests for comment, but TEA data shows the 2020-21 district dyslexia rate was 3.34%. Texas has not yet released 2021-22 numbers.

Kendra Wiggins, the director of the special education and Section 504 program at CISD, said she expects the new testing guidelines will allow the district to catch students who would otherwise be left without assistance.

“It’s a very robust testing that looks at every area of strengths and weaknesses, so it really gives a better picture of the child as a whole to determine what type of programming we want to look at from that,” Wiggins said.

Officials with MISD and CISD said the districts expect to hire additional special education and dyslexia staff as a result of the amendment.

CISD spends $3.6 million to employ about 65 dyslexia interventionists, officials said.

Clover said MISD employs 10 dyslexia interventionists with plans to add more in the future.

“We believe that we will identify more students with [a specific learning disability], and of those students, many will need explicit intervention aligned to their unique learning needs specific to the condition of dyslexia,” Clover said in an email.

Documents from the TEA state there are no additional costs to state or local government required to comply with the new guidelines.

The TEA gives discretion to districts when determining if the dyslexia program will be under the special education programs. Wiggins said some districts are looking to align the programs under one, and this is something that may happen in the future for CISD.

Disadvantages of the system

Laurie Gaines-Peterson is the executive director and co-owner of Diagnostic Learning Services in The Woodlands, which offers support and education for learning disabilities. She said she works with a lot of children who are waiting to be tested and children who were tested but whose parents do not agree with the results.

“In the past, up until this point, dyslexia has really been handled under the general education umbrella,” Gaines-Peterson said. “And what has happened is that a lot of kids have still gone undiagnosed or are still not receiving the right services.”

Gaines-Peterson said while overall the change in testing is beneficial, she believes there are some disadvantages to the new testing requirements, primarily the wait time to receive a test. After consent is given from parents, the district has 45 school days to complete an evaluation and another 30 days to review the results with the parents.

“There are pros and cons—the cons being the wait time. Early intervention with dyslexia is so important,” Gaines-Peterson said.

In addition, Gaines-Peterson said she is concerned districts are not providing enough education to parents to ensure an appropriate decision.

Vollaro said she hopes to see junior high and high school students receive specialized counselors so students have a representative for Section 504 or IDEA-related issues and questions.

“We all want the best for the kids,” Vollaro said. “I support Conroe [ISD] so much; I really do. I just also have different parents that have said that they feel like they don’t know enough to help their kid.”