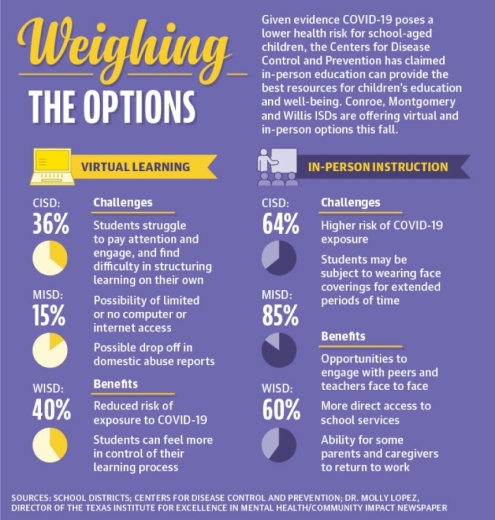

According to the districts, around 64% of CISD students returned face to face, while 85% and 60% of MISD and WISD students returned in person, respectively, and the remainder continued with virtual instruction.

Some parents, educators and experts said they feel in-person education is an ideal model for learning, but health and safety concerns related to COVID-19 are causing many students to remain virtual or carry additional emotional baggage this year. School officials and community members said they are working to ensure adequate resources are available for students’ mental and social well-being.

“It doesn’t matter if you’re in person or if you are at home doing work remotely; we care about you and your whole health. And so you’re going to see investment in our curriculum, in our social and emotional learning, both online and in person,” CISD Superintendent Curtis Null said in an Aug. 24 livestream. “We understand that there has been a mental health strain that’s been associated with everything that’s been going on over these last few months, so we are going to work to make that happen.”

Pandemic pressures

Protecting community health and limiting the spread of COVID-19 have been focuses of public health since the spring, according to district, government and health officials. In that time, entities from schools to organizations such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have also emphasized returning to school as an important step to preserve children’s educational, physical and emotional progress.“Any time there is a combination of high-stress situations and limited face to face, students have increased feelings of sadness, isolation and being disconnected with others,” WISD Director of Communications Jamie Fails wrote in an email. “Willis ISD will remain dedicated to supporting students’ mental health and well-being. It is undeniably the most important factor we must address as we persevere through these unprecedented times.”

While schools shifted to distance learning models this spring—and into the 2020-21 school year as all three districts began virtually in mid-August—educators and family members also noted the downsides to the new model.

“You lose some of the socialization skills because of the environment. You’re also losing the feedback ... for a student who’s quiet, who may not talk—that interaction. Those are the things that are lost,” said Quinita Ogletree, lecturer with the Texas A&M Department of Teaching, Learning and Culture.

Angela Yeh, a part-time pre-K teacher and CISD parent, said families and the district have been faced with tough choices this year to balance such concerns with the potential health downsides that come with a more disconnected school experience.

“My shy 6-year-old is starting the weirdest year yet doing online learning when she should be engaging her social anxieties and growing, learning, becoming. Not to mention that we’re dependent on technology to learn—the one thing I’ve been trying to limit the use of,” Yeh said in an email. “We are, all of us, in a no-win situation.”

Readying resources

CISD officials said the district has invested in resources to ensure students can stay on the same curriculum track whether they return to campus or continue remote learning. In an August presentation, district staff said more than $5 million had been spent on remote learning technology, protective equipment and sanitization.Kim Earthman, the director of CISD Student Support Services, said extracurricular activities can also link in-school and at-home students outside of traditional class hours.

The district’s counseling efforts have also been a constant focus through the pandemic, Earthman said. For example, 159 counselors are available for in-person or online conferences, and the staff also develops workshops for families.

“We provided, in the spring, resources and easy lessons for teachers and for parents to do in the home to address that social and emotional learning,” Earthman said. “We felt that was really important to help kids with those things they were going through and help parents to help their students.”

In addition to providing parent resources, Meredith Burg, the MISD executive director of special education, said educators are being urged to check in personally with students participating in virtual learning.

“We are encouraging our teachers to implement live and recorded [Zoom calls] and/or video lessons. This will hopefully increase connections and negate the isolating effect that virtual learning can perpetuate,” she said in an email.

While the districts work to address those needs, some parents said they are still concerned about the possible social losses or missed connections their children could experience while learning off campus. Laurie Stiles, a parent of two CISD students, said she appreciates some of the ways the district is handling health and social-emotional learning but believes there is still room to improve the district’s virtual support.

“I do believe that this is a significant risk and concern for online learning, particularly for those students who are shy or do not have many friends,” Stiles wrote in an email. “There will be no relationships with teachers, no observations, and we parents have had their education dumped on our laps to deal with on our own.”

Community support

Local counseling center representatives and experts said they expect to see an increase in demand for mental health services from school-age youth in the 2020-21 school year.In addition to counselors offering virtual meetings, Fails said WISD has partnered with Tri-County Services, a nonprofit serving Montgomery, Walker and Liberty counties with behavioral health care, to provide staff with social, emotional and mental health training.

Further, Adriana Gutierrez, the director of counseling services for Yes to Youth—a Montgomery County youth service provider—said the organization has assisted students this year though its telehealth counseling options and new focused skill and support groups, as well as a 24-hour crisis hotline. In addition, Gutierrez said the biggest thing families can do to support children’s mental health is establish a routine.

“Just as if they were in school, set a wake-up time, breakfast time, and a time to start and end their day,” Gutierrez said.

Regardless of whether students are returning to campus or remaining virtual learners this year, Sherry Burkhard, the executive director of the mental health resource hub Mosaics of Mercy, which serves the North Houston area, said it is important educators and parents take care of their own mental health so as to model that for students.

“It’s really important for everyone ... to be on the lookout for kids that are struggling,” she said. “It really requires everyone that’s coming in contact with that kid [to be attentive] because we all may be a little more distracted than usual.”