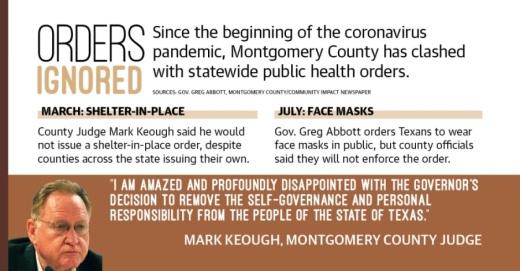

When the first cases of COVID-19 hit Texas in March, Montgomery County trailed behind Harris County in declaring a public health emergency, issuing a shelter-in-place order and limiting large crowds. On April 28, County Judge Mark Keough said all businesses could reopen May 1—despite Gov. Greg Abbott allowing only certain entities to open.

Abbott then ordered all Texans to wear face masks in public beginning July 3. However, Keough and law enforcement officials said they will not enforce the order, claiming it to be unenforceable.

“How do you get 600,000 people to wear masks, make sure they wash their hands?” Keough said July 24.

Whether the county’s approach is helping or hindering the spread of the coronavirus is unclear. Data from hc1—a cloud-based platform that takes COVID-19 data from 2,000 Food and Drug Administration-certified laboratories across the U.S., or about 40% of all the labs in the nation—shows although cases continue to rise in the county, they are growing at a slower rate than Texas as a whole.

Hospitals countywide remain below capacity, with 147 intensive care unit beds in use as of press time Aug. 10, 45 of which are for suspected COVID-19 cases. Still, some health officials claim if cases appear to not be rising as rapidly, the response should be to crack down harder.

“As local county officials, you should really consider mitigation orders, [such as] mandatory masks,” hc1 physician executive Dr. Peter Plantes said.

Mixed messages

Signs of disagreements between Keough and Abbott began several months ago, when the judge announced all businesses could open May 1 while the governor restricted openings to certain businesses. When the face mask order was announced July 2, the county again showed reluctance in enforcing the order.

Sheriff’s office officials said they claim the language in the governor’s order prohibits law enforcement from detaining, arresting or jailing citizens as a means to enforce the order, essentially stripping law enforcement of the tools to enforce compliance.

“I am amazed and profoundly disappointed with the governor’s decision to remove the self-governance and personal responsibility from the people of the state of Texas,” Keough said in a video posted to Facebook in early July.

Mark Jones, a political science fellow at Rice University who specializes in Texas politics, said the attorney general could weigh in on the issue, but it is more likely the state would intervene through regulating bodies such as the Texas Alcoholic Beverage Commission to shut down businesses that do not comply.

Outside of that, Jones said it is difficult to make county officials “enforce things that they don’t want to.”

“The governor is already angering Republicans—many Republicans, many of the more conservative Republicans—by pushing these measures and allowing Democratic-held counties to implement them,” Jones said. “It would probably be too much for them [Republicans] if he actually intervened directly in their localities.”

Public struggles

Despite deeming state orders unenforceable, county officials are still supporting local efforts to test, trace and treat coronavirus cases.

On July 15, the Montgomery County Public Health District announced Keough had granted additional staff and funding to process a backlog of COVID-19 cases, causing a surge of 853 cases in one day. The commissioners also approved the purchase of a $500,000 shelter to deal with overflow coronavirus patients.

According to hospital data compiled by the Southeast Texas Regional Advisory Council, the number of confirmed COVID-19 patients in Montgomery County hospital beds rose in June and July. Although Montgomery County recorded several dozen or fewer general hospital beds used daily in the early months of the pandemic, the number passed 200 in early July. The number of COVID-19 patients in ICU beds peaked at 96 on July 7, which is 46% of the county’s ICU surge capacity.

Debbie Sukin, the CEO of Houston Methodist The Woodlands, said at its peak the second week of July, the hospital system as a whole was treating around 700 coronavirus patients.

Health officials said coordinating between facilities has been essential.

“We’ve been working with [the SETRAC] to make sure patients are placed throughout the region,” said Dr. Sayed Raza, the vice president of medical operations at CHI St. Luke’s Health-The Woodlands Hospital.

And while hospitals began to exceed their regular capacity, Sukin reported as of Aug. 3 there had been a decrease in coronavirus patients over the past week, and 500 patients were being treated at Houston Methodist hospitals.

Local Risk Index

As for overall cases, Montgomery County is growing, although not as much as Texas as a whole, according to hc1’s data. Hc1 debuted its Local Risk Index in April, which reports the percentage of those who tested positive by nasal swab for COVID-19 in the current week.

The LRI value indicates the level of active infection in an area and the risk individuals in the area face of contracting the virus.

An upward trend in the LRI value serves as an early warning the prevalence of infection may be rising, according to hc1. A downward trend indicates the level of infection is falling.

The baseline LRI value is 1 because 1% prevalence is the threshold below which outbreaks of respiratory viruses can be controlled by self isolating positive cases, according to hc1. A value above that indicates broader mitigation measures, such as social distancing and mandatory face masks, are required, Plantes said.

Montgomery County has seen an increase in its LRI value since March, growing from 5.26 on May 31 to 18.66 by July 31. The peak as of press time was 21.90 on July 21. However, the value began declining in early August, falling to 12.50 on Aug. 8. The county also saw less growth than the state, which grew from 6.95 on May 31 to a peak of 22.98 July 19 to 16.03 by July 31.

“That’s a pretty good rate for a smaller county,” Plantes said.