That requirement is still in place two years later, but health care advocates in Texas and Houston said they are worried about what could happen when it ends and millions of people have their safety nets put into jeopardy.

In September 2021, the Urban Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank, estimated as many as 1.3 million Texans could be deemed ineligible for Medicaid once the public health emergency ends. Roughly 3.7 million of the 5.3 million Texans enrolled in Medicaid will have their eligibility redetermined once the emergency ends, according to the Texas Health and Human Services Commission. Roughly 73.2% of Texas Medicaid enrollees are children, according to the latest HHSC data.

“Our main concern is you are looking at huge numbers having to reapply, and that’s going to take a lot of time to go through,” said Brian Sasser, chief communications officer with the Houston-based Episcopal Health Foundation, which works with health care nonprofits across Texas.

The pandemic also shined a spotlight on a debate that has been ongoing in Texas since 2010: whether the state should expand Medicaid to cover more people. That debate will come up again when the state Legislature meets in January, and some local lawmakers said they are ready for change.

State of Medicaid

The public health emergency was still in place as of May with an expiration date of July 15. However, the government also requires a 60-day notice before Congress can allow the emergency to expire. That notice was not given May 15, meaning the emergency is likely to be extended into October, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a group that analyzes federal and state budget policies.

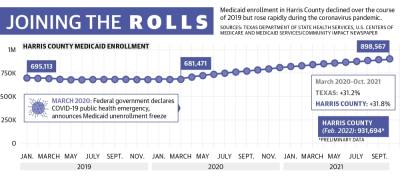

In Harris County, the number of people enrolled in Medicaid hovered in the high 600,000s prior to the pandemic with little change between 2017 and 2020. Since then, the county rolls grew to 898,567 as of the most recent confirmed data from October 2021. The HHSC’s preliminary data from February estimates around 932,000 county residents are now enrolled in Medicaid.

When the public health emergency ends, a portion of Medicaid enrollees will have their coverage automatically renewed if they are deemed eligible. There will also be an unwinding period of up to 12 months during which states are to work with individuals who were not automatically re-enrolled to help them keep their coverage if they are still eligible, though a May 5 HHSC presentation on the end of continuous Medicaid coverage indicated that Texas plans to only use six months.

For states to succeed, they will have to focus on streamlining the application renewal process and communicating effectively with enrollees, said Farah Erzouki, senior policy analyst with the CBPP.

“These steps will be key to make sure people can be reached, that they know what changes are coming and they know what they need to do to keep their coverage,” Erzouki said during a May 18 press briefing.

The CBPP recommends states increase capacity for renewals that are determined using electronic data matches, which will help avoid having to rely on enrollees to complete a renewal form or submit documentation, Erzouki said. Texas uses those kind of renewals in less than 25% of its processes, according to data from the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonprofit focused on health care issues.

Additionally, Erzouki said it will be crucial for states to allow enrollees to renew their policies through a variety of methods, including online, by phone, by fax, by mail and in person. Texas is among the 33 states to allow renewals by all five methods, according to the KFF.

State preparations

There is no estimation from the HHSC at this time for how many people could be determined ineligible and unenrolled when protections expire, HHSC Press Officer Kelli Weldon said. Some decline in the current enrollment figures is considered inevitable as the state works to remove people who no longer qualify for a variety of reasons.

Officials will get a better idea after they conduct a full analysis during the unwinding period, Weldon said.

"As HHSC plans for the end of the public health emergency, we will continue working with government partners, including managed care organizations, the enrollment broker, providers and local community partners to ensure a smooth transition," Weldon said in an email. "To support this collaboration, HHSC launched an Ambassador Toolkit that contains materials and information to support Medicaid clients in preparing for the end of continuous Medicaid coverage."

The continued coverage requirement in the public health emergency has been vital to those on Medicaid, Sasser said.

Before the pandemic, individuals on Medicaid had to regularly renew their policies, which Sasser said can be burden for many families depending on how often they have to reapply.

“If you had to keep reapplying to that and updating your income, that’s a hassle,” Sasser said. “This pandemic emergency act allowed that to go away for a bit.”

Sasser said he is concerned about the state giving itself enough time to adequately review each case. If Texas does not plan ahead, it could result in people getting kicked off Medicaid for paperwork reasons when they are otherwise still eligible.

“With Medicaid, you are dealing with pregnant moms and children,” he said. “You are dealing with folks who need the care the most and who need timely care the most.”

Children are most at risk of being unenrolled when the public health emergency ends, said Laura Dague, associate professor with the Texas A&M University Public Service and Administration Department who specializes in the economics of public health insurance.

“The vast majority—and that means, of course, the people who kind of stayed on [Medicaid] longer than expected—are low-income kids. I think we will see the most disenrollment in that group,” Dague said.

Debate over expansion

Certain population groups are eligible for Medicaid in Texas if they fall below a certain income level that varies by program. People who are pregnant, are children, have a disability or are over age 65 all may be eligible depending on family income.

The health care policy is jointly funded by states and the federal government with the federal government paying 90% of the cost of health care for those insured by Medicaid and states paying 10%, according to the KFF.

When the federal government signed the Affordable Care Act into law in 2010, each U.S. state was given the option to expand Medicaid coverage to nearly all adults with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level, an annual income of $17,774 for an individual in 2022, according to the KFF.

Texas is among 12 states that have not expanded Medicaid. Of the 12 states that did not expand Medicaid, Texas generally has set the highest bar for people to qualify based on income, according to KFF. Based on a single parent household with family size of three, a Texas resident must have an income at 16% of the federal poverty level, according to KFF.

As a result, Texas has the highest rate of uninsured individuals of all states, according to the KFF. Nationally, about 8.6% of people are uninsured, compared to 17.5% in Texas.

Researchers with Texas A&M University released a study into the economic effects of Medicaid expansion in 2019. The study found expanding Medicaid would make 223,700 more people eligible in Harris County and result in 167,500 new enrollments. Expansion in Harris County would come at a cost of $949.9 million to the federal government and $105.5 million to Texas.

Ahead of the next legislative session, which will kick off in January, several local representatives said Medicaid is top of mind. Those opposed to expansion say Texas would still be on the hook for program costs and question the effects it would have on improving health care outcomes in the state.

“Medicaid expansion ... does not necessarily equal expanded access to care. Many providers in Texas do not accept new Medicaid patients,” Republican state Rep. Cody Vasut said, citing a 2013 survey by the Texas Medical Association that found roughly 31% of Texas doctors accepted all new Medicaid patients.

With the state paying 10% of the costs, that could still exceed $500 million, Vasut said.

"It is also unclear if the present federal split would be maintained in the future or if Texas would end up having to pay an even higher percentage," Vasut said.

In an April 2020 report, the conservative think tank Texas Public Policy Foundation argued that targeted improvements to health programs, such as programs geared toward children, would yield better health outcomes than broader Medicaid expansion.

Democratic state Rep. Ann Johnson said she is a staunch supporter of expanding Medicaid, which she said is long overdue in the state.

Johnson supported expansion during the 2021 state legislative session while also co-authoring several bills designed to improve the system. The proposed expansion bill included a caveat that, if the federal government were to ever remove funding, Texas would no longer be obligated to keep expanded Medicaid in place. The caveat was meant to get more opponents on board, but the bill still failed, Johnson said.

Another bill to study the cost to Texas of not expanding Medicaid over the past five years also failed along party lines, Johnson said.

"I think we all know what it would show, which is this is a poor economic decision for the state of Texas," Johnson said. "Because when people get sick, they still show up at the [emergency room]. There is still a cost to be distributed, but it's being distributed unevenly."

Johnson co-authored House Bill 133, which expanded care to women who had just given birth for six months, up from two months. Although the Texas House of Representatives passed a version of the bill that provided care for 12 months, the Senate amended it to only provide six months.

“We should be taking care of the most vulnerable in our state,” Johnson said.

Sierra Rozen contributed to this report.