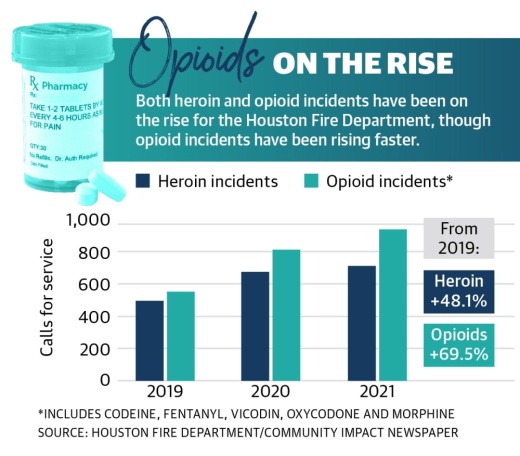

The number of calls for service made to the Houston Fire Department for opioid and heroin incidents grew from around 40-60 per month in early 2019 to 140-160 per month in late 2021 and early 2022, said Dr. Chris Sounders, associate medical director with the HFD.

Statewide, data from the National Center for Health Statistics shows reported opioid overdose deaths are rising. The 12-month total of opioid overdose deaths increased from 1,431 in November 2019 to 2,628 in November 2021, the most recent data available.

“These are diseases of despair that we’re dealing with,” said Tyler Varisco, a health services researcher with the University of Houston. “When people are economically challenged or psychologically challenged as many of us have been over the past two years, we see increased vulnerability in our communities to opioid use and other forms of substance misuse.”

With increased isolation and financial stresses, the COVID-19 pandemic further compounded struggles against the opioid epidemic in Texas, experts said. Recovery treatment transitioned into less effective online services, and access to quality treatment, such as medication, became more complicated.

Dr. Ericka Brown is the director of Harris County Public Health’s Community Health and Wellness Division, which oversees the countywide Opioid Overdose Prevention Program. She said local treatment services were limited during the pandemic’s peak, but several federally funded programs aim to provide resources to mitigate drug use in high-risk areas locally.

“While we don’t specifically name that as a public health crisis, inequity across not just Harris County, but across the country, as we look at those who are underserved and the lack of resources for them is really a public health crisis. And unless and until we address that, we’re going to continue to see some of these epidemics flourish,” Brown said.

Opioid use over time

Brown said countywide, white men are the most likely demographic to misuse opioids, although the epidemic also affects communities of color.

“These are the folks who, through multiple surgeries and just regular health-related incidents, have been addicted to prescription opiates and are now switching to illicit supplies of it, causing the overdoses,” she said.

In 2010, about 69 opioids were prescribed for every 100 residents of Harris County. A decade later, the number had fallen 45%, according to data from the Texas Department of State Health Services. However, a little more than one prescription was still issued on average for every three county residents in 2020, the latest data available.

While prescription misuse is still an issue to some extent, Brown said the county is seeing a rise in street drugs, such as lookalike prescription medications and fentanyl, a highly lethal opioid. The use of fentanyl in Harris County has risen by more than 100% since 2019, she said.

When the HFD responds to an opioid call, responders are more often finding victims are overdosing on drugs that were laced with synthetic lab-made compounds. Sounders said these can be far stronger than heroin or morphine and can have wildly variable effects.

During an opioid overdose, the opioid acts as a respiratory depressant, which stops the body’s mechanism that helps a person breathe, Sounders said.

Since 2018, all HFD apparatuses—including fire engines and ambulances—have been outfitted with nasal spray versions of Narcan, a device that dispenses naloxone, which can help treat narcotic overdoses in emergency situations.

“You need to be really careful about buying stuff off the streets,” Sounders said. “They can be so strong that we don’t even carry enough Narcan to reverse them.”

Pandemic effects on treatment

Varisco said the pandemic exacerbated several underlying causes of substance use, including patient access to treatment, increased financial stresses and isolation. He said he believes the changes to health care for individuals experiencing addiction undid recovery work performed for patients before the pandemic.

In addition to chronic stress, the pandemic also affected some people’s sense of self in ways that made them more open to engaging in recreational drug use, said Dr. Daryl Shorter, medical director of addiction services with the Menninger Clinic. Based in southwest Houston near the Willowbend area, Menninger provides withdrawal management services to people who come to the clinic from all over the world.

“More people are more likely to use substances, and among those who are more likely to use substances, there is now a subset of those who are more likely to develop a substance abuse disorder,” Shorter said.

According to the Treatment Episode Data Set, which compiles national patient discharges from treatment for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, detoxification treatment discharges became less common from 2016-19, when detoxification discharges decreased from 20% of all discharges to 16%.

“When you have a destabilizing event like a global pandemic, [vulnerabilities in health structures] become more evident,” Varisco said.

Moving forward, it will be crucial to treat substance use disorders like medical conditions as opposed to moral failures on behalf of those who are suffering, Shorter said. Under the moral model, patients may not receive the treatment they need because of an unconscious bias that patients need to suffer as part of the detoxification process, he said.

The push to make Narcan more accessible is also paramount, Shorter said.

“If we want to start stemming the tide of these deaths, Narcan needs to be everywhere,” Shorter said.

Government solutions

Around 2019, the HFD began a grant-funded partnership program with Houston Recovery Center with the goal of getting more people who overdose into treatment centers. Under the partnership, first responders with Houston provide real-time notifications of Narcan use to wellness advocates with the HRC, who are then able to respond to the hospital where they can attempt to meet the patient and talk to them about overdose education and the basics of getting help.

“They go to the hospital and try to intervene and offer resources to the patient within an hour of transport,” Sounders said. “The research shows this is the most effective time to try to get someone to make an actual change in their life. ... You are more receptive to that help rather than if you go home, and someone offers to help you five days later.”

At the county level, Brown said HCPH’s Overdose Data to Action program collects overdose data to inform local prevention and response efforts. HCPH also partners with the Harris County Sheriff’s Office to identify areas of high risk and provide resources to mitigate crime and drug use in those areas in the Violence Prevention Program.

Statewide, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton announced Feb. 16 that the state had secured a $1.17 billion settlement with three major pharmaceutical companies: AmerisourceBergen, McKesson and Cardinal. According to the attorney general, Texas has secured $1.89 billion to date from opioid settlements.

Paxton’s office is also encouraging local governments to sign onto existing settlements to receive funds. According to the attorney general’s website, 482 Texas municipalities signed onto two settlements with Janssen—owned by Johnson & Johnson—and with AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health and McKesson.

The city of Houston will get more than $7 million from the settlement, according to documents from Paxton’s office. The city of Bellaire will get just over $41,000, while the city of West University Place will receive about $34,000. Cheryl Bright, community relations administrator for Bellaire’s city manager, said recommended uses for the funds include fire fighter, paramedic and police officer training, as well as educational awareness and supplies needed to treat victims of opioid abuse when in the field.

Lee McColgin is a liaison for the Houston Recovery Center who was addicted to opioids and used them for 35 years on and off. He encouraged people to disregard any previous notions they might have had about opioids.

“This idea that it’s only heroin addicts and hardcore drug addicts that are overdosing on this stuff has to be completely eliminated, or else we miss the most vulnerable people,” he said.

Danica Lloyd and Sierra Rozen contributed to this report.