Correction: Ryane Jackson serves as Vice President of Community Benefits with Houston Methodist.

Long COVID-19: Patients continue to face symptoms months after diagnosis

In July 2020, Mikkia Dawson contracted COVID-19.What this former Houston pediatric nurse experienced was not mild flu-like symptoms but rather the entire gamut of what the coronavirus can inflict on a person’s body.

“I was sick for probably three weeks, like really sick, and I had every symptom,” Dawson said. “I lost my taste; I couldn’t breathe; I was under respiratory distress, and I had a terrible cough.”

After a week, Dawson experienced food poisoning-like symptoms, including intense cramping and diarrhea. Her fever reached a high of 103 degrees.

Dawson weathered the storm, however, and by mid-to-late August thought she had beat the disease.

But on Aug. 29, Dawson had a stroke caused by small blood clots on the left side of her brain.

“My neurologist told me that what had been happening, even in patients a lot younger than me, [was] that patients who had battled with COVID had issues with blood clotting really fast,” Dawson said. “They didn’t know why that was happening, but it was starting to be a trend.”

As a result of the stroke, Dawson was referred to TIRR Memorial Hermann, which offers a COVID-19 Rehabilitation Program for inpatient and outpatient rehab and an outpatient medical clinic.

Dawson is one of a growing number of people experiencing long COVID-19, defined broadly by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as a wide range of symptoms lasting for weeks or months after being infected with the coronavirus.

Studies of the condition remain in the early stages, though Johns Hopkins University estimated in March that 10%-30% of all COVID-19 patients reported experiencing long COVID-19 symptoms.

Locally, Baylor College of Medicine’s Post COVID Care Clinic launched in February and had taken on at least 200 patients by April.

“We are getting a lot of patients from the community,” said Dr. Fidaa Shaib, associate professor of medicine in pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine for Baylor. “It’s a matter of increased awareness of this entity, the National Institutes of Health, the scientific community giving [long COVID-19] a name, making it a research priority.”

Other local institutions have their own version of a post-COVID-19/long COVID-19 clinic, including Harris Health Ben Taub Hospital, the University of Texas Health Science Center and the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, among others.

Meanwhile, a journey to recovery still remains before Dawson, who was let go from her previous nursing position May 7 while she underwent long COVID rehabilitation.

Still, she remains optimistic.

“I’m going to focus on me and getting better, however long that takes,” Dawson said. “Maybe I will get into a different part of nursing that is not as physically demanding. My goals will look different now.”

Education, outreach look to curb decadeslong vaccine challenge

The vaccination effort has dominated discussions of returning to “normal” for months, both in Houston and across the U.S. However, earlier this spring local public health officials saw a shift in vaccine demand. Instead of people signing up for vaccines as fast as they could be delivered, the city of Houston found itself needing to go into communities to reach out directly to those who had not yet been vaccinated.Of the estimated 24.1 million people who are age 12 or older in Texas, roughly 11.3 million of them have yet to be vaccinated as of June 2, according to the Texas Department of State Health Services, which tracks vaccination numbers. Health officials now say those community outreach efforts are key to eventually beating the virus.

In an effort to improve those numbers locally, Legacy Community Health—which has a location in Bellaire—is educating its patients on the safety and efficacy of the vaccines while struggling to fill appointments.

“A lot of concerns I’m hearing, whether it’s from patients or patient families, is the safety of the vaccines,” said Dr. Amelia Averyt, the network’s associate medical director for clinical family practice.

The Houston Health Department has also formed community partnerships with a variety of organizations and nonprofits across the city, including the Third Ward and Houston’s North Side. At the same time, hospital systems like Houston Methodist have formed community partnerships of their own to host vaccine drives in places like the Heights and Acres Homes.

“These kinds of partnerships have been critical throughout the entire vaccine effort,” said Ryane Jackson, vice president of community benefits with Houston Methodist. “Early on, we found the key to success for reaching people for these vaccines was partnerships with local nonprofits who are already known and trusted by the exact communities we’re targeting.”

Houston Methodist hosted vaccine drives at the Heights Theatre in May and June aimed at the live music community. Also in May, Houston Methodist hosted a vaccine drive in Independence Heights, partnering with the Houston Food Bank and the local nonprofit Lucille’s 1913, which brought pre-cooked meals to distribute to people who got vaccinated.

“We’re all about community issues, so it was a perfect fit for us,” said Robertine Jefferson, director of development with Lucille’s 1913.

At One Delta Plaza Educational Center—a Third Ward nonprofit that has partnered with the city of Houston on several vaccine drives since April—Board Chair Bernadine Duncan said her team went door to door working with local business owners to find times for employees to walk down and get vaccinated during their breaks.

“It’s all about being genuine and telling people in our own language, ‘This is what we need to do,’” she said.

Averyt emphasized the vaccines are safe, and said reassuring hesitant patients has been key to correcting inequities in vaccine distribution. Of the nearly 2 million people in Harris County who have received at least one dose, Hispanic and Black people make up nearly 33% and 11%, respectively. For context, Hispanic and Black people make up 44% and 20% of the county’s overall population, respectively, according to 2019 U.S. Census Bureau data.

Ongoing issues for underserved groups include language barriers and transportation challenges.

Ongoing issues for underserved groups include language barriers and transportation challenges.“There is also a lack of established trust with the health care system before the pandemic started,” Averyt said. “If you aren’t getting regular health care, you probably aren’t used to getting messages about vaccines, comfortable with getting vaccines, being told what to do with your health.”

Texas Southern University is doing similar work in the Third Ward, where officials opened a clinic in February with St. Luke’s Health.

However, the challenge is also about opposing efforts to delegitimize the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines. Tackling the issue takes a several-pronged approach, but transparency from the medical community to the public is key, said Dr. James McDeavitt, the dean of clinical affairs at Baylor College of Medicine.

“I think we have sometimes made the mistake of talking down to the public,” McDeavitt said. “We need to engage with them in that science. I think that sets people’s expectations of what they can expect from science.”

Dr. Peter Hotez, professor and dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine and co-director of the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development, has been opposing anti-vaccination efforts for decades.

“The flip side to this conversation is that the anti-vaccine disinformation empire is massive,” Hotez said. “The Center for Countering Digital Hate finds that anti vaccine groups on social media have 58 million followers. We have that problem.”

The number of people showing up to vaccine drives is not as large as it was earlier in the year, Jackson said, but she said progress is still being made on the path to reaching herd immunity.

“As long as we keep doing events like this and working to find what moves people ... we will get there eventually,” she said.

Doctors warn against delayed checkups as new COVID-19 treatments spark optimism

Outside of vaccines, new health care treatments are emerging to help combat COVID-19, said Dr. Shawn Nishi, associate professor and fellowship program director with the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.

Treatment options undergo what is called an Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial. The most famous of these trials was used for antiviral drug Remdesivir, approved by the Federal Drug Administration on Oct. 22 to treat COVID-19 patients who were hospitalized and required supplemental oxygen. But other treatment options exist.

For nonhospitalized patients with mild to moderate COVID-19, it is common for monoclonal antibody treatments to be prescribed, Nishi said.

“There are several out there on the market now, and essentially these are IV infusions,” she said. “There are some research projects ongoing right now for pill versions, but none of these are available right at this moment.”

New drug development is pushing forward at the same time doctors have warned about the potential consequences of people delaying health checkups over the past year.

“I have plenty of patients who have put off their diabetes care, monitoring their blood pressure, regular cancer screenings, annual exams and of course in our pediatric population,” said Dr. Averyt, the associate medical director of clinical family practice at Legacy Community Health.

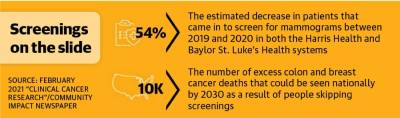

This extends to cancer screenings, where it is estimated that 54% fewer patients came in to screen for mammograms between 2019 and 2020 in both the Harris Health and Baylor St. Luke’s Health systems.

“The good thing is a lot of cancers are very slow growing, so hopefully a few months to a year of delay of your regular routine screening won’t cause too many problems,” Averyt said. “But it’s definitely important to keep in mind and get back into care for those screenings.”