These neighborhoods, such as Independence Heights and Freedmen’s Town are the sites of recent change—such as gentrification through commercial and residential development as well due to extreme weather events, like Hurricane Harvey—which cause a loss of character, said Mayor Sylvester Turner at a Feb. 22 public hearing regarding the draft ordinance.

In a 13-4 vote, the conservation district ordinance was approved by Houston City Council on April 5. This ordinance paves the way for local protections for six neighborhoods: Independence Heights, Freedmen’s Town, Manchester/Magnolia Park, Plesantville, Piney Point and Acres Homes. It also allows for future conservation districts, after the initial six.

At-large Council Member Mike Knox was among those who voted against the ordinance, arguing for language to be added that would allow for property owners to opt out. However, Mayor Sylvester Turner said such a change would dilute the point of the ordinance. He emphasized the ordinance only pertained to the six specific communities, and that more conversations will take place between residents in those communities and city officials before any one district becomes official.

“You are going to have plenty of community engagement and discussion in these respective districts,” Turner said at the April 5 meeting.

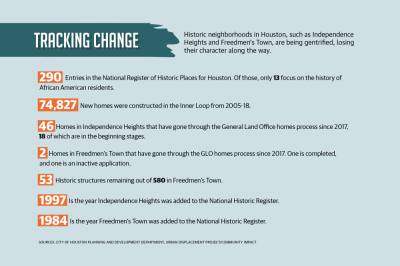

Independence Heights was settled by Black people in the 1900s and became the first African American municipality in Texas, while Freedmen’s Town was founded by newly freed slaves during the Reconstruction Era, beginning in 1865, said Roman McAllen, officer with the Houston Office of Preservation.

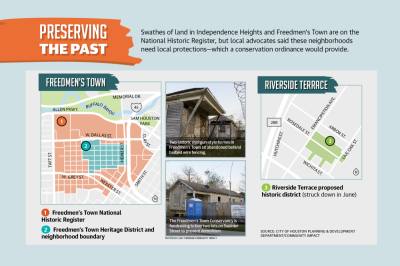

Both of these Houston neighborhoods are on the National Historic Register, added in 1997 and 1984, respectively, but this national recognition provides no local protections of the integrity of historic neighborhoods, McAllen said.

“If you’re on the national register, just the way the law is written, it doesn’t require that that building or house be preserved,” he said. “So local laws and local rules and local ordinances are what impact local buildings.”

Debating the draft

Conversations around conservation districts began more than a decade ago for Independence Heights, which first discussed it in 2012 during Houston’s Livable Centers study.

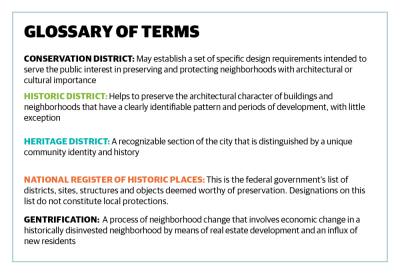

A conservation district will be a more attainable form of protection than historic districts, which offer a higher buy-in, requiring a minimum of 67% approval from residents. The conservation district ordinance requires 51% approval for the six pilot neighborhoods to initiate the process.

Any district that does not have 100% community buy-in would also go back to the Houston City Council before approval, Turner said April 5. A conservation district would also provide flexible standards neighborhoods can pick and choose from—such as roof pitch and building setback—for how to maintain the character of their neighborhoods. It differs from a historic district, which has standards that are more fixed.

A heritage district is the third type of local district for protecting a neighborhood with a unique identity and culture. Heritage districts only apply to publicly-owned land.

Beginning in 2020, the Planning and Development Department conducted a series of focus groups regarding conservation districts. Despite this residents—including public speakers at the Feb. 22 public hearing at Houston City Council—expressed concerns over the process feeling rushed.

The draft for the ordinance has progressed through the city in a matter of weeks, since it was published in February.

This ordinance would inherently limit the types of development allowed in a neighborhood. Planning and Development Department Director Margaret Wallace Brown said deed restrictions will always take precedence over this potential ordinance.

The idea for the conservation ordinance was inspired by neighborhoods like Independence Heights, Turner said at the Feb. 22 public hearing.

“These communities are being gentrified; they are being wiped out,” he said.

Tanya Debose, a fifth-generation Independence Heights resident, said the conservation district ordinance would be just another tool for residents in the historic preservation toolbox.

“What the conservation district does is it allows us in the community who own the property, to say, ‘Here’s what we know as the identity of our community. These are the elements that we feel like need to be protected,’” she said. “That if anyone drove into this space, they can know that something great happened here, something historic happened here.”

Neighborhoods to note

Independence Heights encompasses about 45 blocks, north of Greater Heights, including numbered blocks from 30th Street to 45th Street. It is home to many vacant lots and faces a high rate of residential development, Debose said. There are several projects on 38th Street alone, which falls in the middle of the neighborhood’s numbered streets and runs through the neighborhood’s major thoroughfares, Yale Street and Main Street.

According to the Texas General Land Office, which repairs and rebuilds homes affected by Hurricane Harvey through its Homeowner Assistance Program, there have been 46 applications for new homes in Independence Heights since Hurricane Harvey in 2017, and 18 of these applications are in the initial intake stage.

“The General Land Office uses contractors and about four designs of housing, and tell[s] our people to choose from them. Nobody who’s being contracted has a background in history, historical architecture, anything,” Debose said. “And so we feel like this conservation district can at least set a standard that when you do come into this community to rebuild it, don’t build against the designs that are there [and] that represent the historical character and significance of the community.”

While Freedmen’s Town—40 blocks founded by freed slaves as early as 1865—does not face the same GLO home challenges, it does battle a fight against time. McAllen said when he biked through Freedmen’s Town in 2020, only 53 out of 580 previously cataloged historic structures remained.

Freedmen’s Town became Houston’s first Heritage District in June 2021. Freedmen’s Town Conservancy President Zion Escobar has championed the fight for preserving the community.

“Our intention is to protect and preserve Freedmen’s Town in town for the benefit of future generations. Our other intentions are to trigger investment into this place, which has been divested in, has been set aside,” she said. “And so what we aim ... to make sure that the heritage is front and center, and that people understand that this place is special.”

The Freedmen’s Town Conservancy is fundraising for $300,000 after it “overpaid” to acquire two neighboring properties from a developer in December, said Bill Baldwin, the fundraising coordinator for the project. The lots are 1609 Saulnier St., which is the site of a historic home in need of repair, and adjacent vacant lot at 1611 Saulnier St. Baldwin said 1609 Saulnier St. will be restored and sold by next December, and the plan with 1611 Saulnier St. is to either build a period-correct home on the lot or move a threatened historic home to the lot.

Working with change

Some residents like Escobar said this fight is not new. Residents of these historically Black neighborhoods have been fighting natural disasters and construction—by means of developers and new highways—for decades, Escobar said.

In February, METRO and city officials found 33 remains from historically Black cemetery Evergreen Negro Cemetery. In the 1960s, the city expanded neighboring Lockwood Drive, causing the disruption of 490 bodies from the cemetery, according to the Texas State Historical Commission, which deemed the cemetery historic in 2009.

Concerned residents—including those from Riverside Terrace, who fought against a proposed historic district designation in June 2022—conducted a town hall on March 8 at the Harris County Justice Courts office on Cullen Boulevard to discuss the potential ordinance.

Although Riverside Terrace residents were initially concerned that the ordinance was too vague and could create financial burdens, they acknowledged that concept itself would be a useful tool for the communities that want it.

Both Debose and Escobar expressed interest in development in Independence Heights and Freedmen’s Town, respectively, under the right circumstances.

“We’re not against density. We’re not against wonderful new people with opportunities and a vision that is in alignment with the community coming into the community,” Escobar said. “But it’d be great if it just looked like it belongs here, as opposed to anywhere else.”

The ordinance will go into effect on May 5, 30 days after its approval by the Council. Moving forward, the city’s planning department will work with the neighborhoods named in the ordinance to design the parameters.

Shawn Arrajj contributed to this report.