Three concepts, each with their own phases of engineering and construction, have come before the three entities that are working towards regional solutions: Bellaire, Harris County Flood Control District and the Texas Department of Transportation.

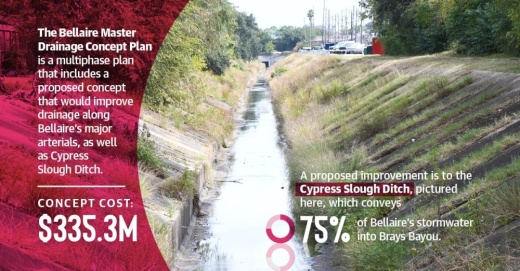

Two of the three concepts have thus far been dismissed for their impracticality. A $335 million plan known as Concept C remains in play, focusing on upsizing Bellaire’s existing systems and improving Cypress Slough Ditch.

The plans come as Bellaire looks to alleviate its longstanding flooding concerns with widespread community support, said Chris Canonico, a Bellaire resident, licensed engineer and member of the Bellaire Flood Hazard Mitigation Task Force, which identifies flooding hazards and solutions.

“Everyone wants to improve our resiliency,” he said. “Everybody is engaged, and we want to improve the conditions in Bellaire as best we can, and we’re all behind that.”

Bellaire residents are no strangers to flooding. Tropical Storm Allison, which battered the Gulf Coast in June 2001, flooded more than 1,400 homes in Bellaire, while the Memorial Day storm of 2015 flooded more than 200 homes, according to a 2017 post-Hurricane Harvey report.

When Hurricane Harvey hit in August 2017, peak rainfall reached between 5,000-20,000-year storm levels across the Bellaire, Meyerland and West University Place area, according to the HCFCD. Harvey flooded more than 2,300 Bellaire structures.

These outlying events would have caused flooding no matter the degree of preparation, Bellaire-contracted engineers said. However, in a 13-month period starting with the May 2015 storm, Harris County—including Bellaire—experienced six flood events with over 8 inches of rainfall, highlighting the need for Bellaire to make storm sewer improvements.

In light of those events, Bellaire started working in January 2020 to create a master drainage concept plan. Work will build on $149 million the city has spent on local drainage infrastructure improvements as part of its 2000, 2005 and 2016 bond programs.

“Designing for Harvey was never the target with this plan,” Bellaire Public Works Director Mike Leech said. “Designing to make improvements against much more common storm events is the tactic we undertook here.”

The flooding problem

Bisected by Loop 610 and located in the midst of the Brays Bayou watershed, Bellaire has traditionally flooded due to a host of factors, including low topography, according to officials with Bellaire’s contracted engineering firm, ARKK Engineers, in an interview with Community Impact Newspaper.

The city’s existing underground drainage infrastructure is designed to carry the load of a two-year storm but only on newer streets, according to ARKK. That is defined as 5.1 inches in a 24-hour duration, said Stephen Wilcox, partner and project manager for civil engineering firm Costello, which collaborated with ARKK Engineers during the creation, modeling and revisions of the drainage plan.

The city’s major outfalls—north-south systems such as Loop 610, Newcastle Drive, South Rice Avenue and Chimney Rock Road—would ideally be capable of handling a 100-year storm event, or 16.9 inches in a 24-hour duration, Wilcox said. However, the systems are currently unable to contain a 100-year storm event nor a two-year event, ARKK Engineers wrote in the 2016 drainage study.

Meanwhile, Cypress Slough Ditch, a 9,300-foot channel that runs along Bellaire’s southern border and conveys 75% of the city’s stormwater, should be capable of containing a 100-year storm event. But the largest section of the ditch cannot adequately handle a 10-year storm event, according to the 2016 study. This means any storm above that intensity would cause water to crest the banks of the channel and move into nearby structures.

When these major drainage systems were first developed in the 1950s and 1960s, Bellaire was mostly prairie land, according to the study. Subsequent improvements to these drainage ditches helped but were not sufficient enough as Bellaire built homes and businesses with paved streets, driveways and terraced lawns, which increased the rate of stormwater runoff, ARKK reported.

“When the city developed, it developed in pockets,” ARKK Engineers principal James Andrews said. “Developers that put in a subdivision didn’t really plan on overland flow coming from another area into their area and out of their area trying to get to the ditch. They just took care of their immediate section.”

“As for why Bellaire floods, you have Brays Bayou flooding, which could happen independent of Bellaire having any rain, and you have the local rainfall, which theoretically could happen independent of Brays Bayou,” Wilcox said. “Harvey was both of those at the same time, times two.”

Regional solutions

After Hurricane Harvey ravaged Harris County, voters approved a $2.5 billion bond referendum in August 2018 to support flood damage reduction projects by the Harris County Flood Control District. Of that, $1.2 billion was approved for channel conveyance improvements to be carried out through partnership programs, according to the district’s website.

The Bellaire master drainage plan was born from discussions between Bellaire, Andrews and the HCFCD with the goal of identifying flooding dynamics and investigating solutions to improve capacity along the Cypress Slough Ditch, which has been maintained in turns by the HCFCD and the city of Houston, Andrews said.

Alleviating structural flooding has remained top of mind for the engineers working on the plan, Wilcox said.

“The whole goal is to reduce flooding as much as possible,” he said.

TxDOT was pulled into the conversation when the negative effects of Loop 610 on Bellaire’s sheet flow resurfaced. According to Wilcox, the highway acts as a dam for sheet flow, and water gathers on the west side of the highway as a result. The highway’s undersized storm sewer capacity can be tied to both Bellaire and TxDOT drainage systems, Andrews added.

At a cost of nearly $702,000, the drainage plan not only looks at Bellaire, but also the connecting tributaries and ways to alleviate flooding.

“Early on we provided a matrix of what you could do—here’s what it would cost, here’s the benefit you would get and here’s the disruption that would be had to the city while it was being constructed,” Wilcox said.

What started as dozens of concepts were eventually condensed down to three. The vetting process included input from the flood hazard mitigation task force, formed in October 2017, a couple of months after Harvey.

That group, which meets on a by-need basis, last met Sept. 28 to provide feedback and recommendations on a draft plan.

The first of three proposed concepts, the $770 million Concept A, would have built a new channel along Baldwin Avenue in Bellaire’s Southdale neighborhood. Going with that concept would have meant removing approximately 22 homes to make room for the new channel.

That concept was ultimately axed by residents and City Council starting with discussions in November 2020.

“We told them it’s not a desired outcome of the residents on this committee that we take up land to go do that,” Canonico said.

Concept B, meanwhile, proposed a large-diameter tunnel down Loop 610, bypassing Cypress Ditch and tying into Brays Bayou directly. The deterrents to this plan were a nearly $541 million price tag and tunnel construction that would require significant upfront investment, Andrews said.

Concept C presents a more modular approach to engineering and construction with multiple phases that can be done individually, Wilcox said.

“You can progress through it and match it to a funding program as opposed to the other [options], where you need large initial expenses [and], otherwise, you wouldn’t be getting any benefit,” Wilcox said.

The final report of the plan is still in the works, according to Andrews, and it could be released by the end of 2021. From there—should the city opt to pursue Concept C—Bellaire, TxDOT and the HCFCD will decide on which projects to start.

According to Leech, preliminary engineering could start within six to eight months, depending on how those conversations go. Prior to that, officials will need to determine time estimates and how the projects could be funded.