“Everyone was in a lull last year,” said Lyons, who owns six restaurants in the Greater Houston area, including one in Bellaire. “There was so much inconsistency with operations. Nobody knew if we were even going to be open at 50% next week, 100% or 25% the next, or any of those things.”

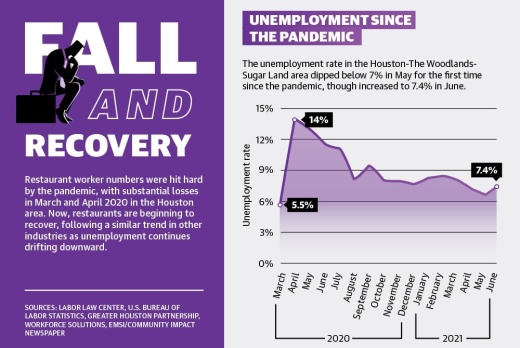

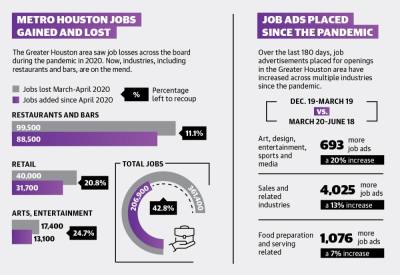

Restaurants are facing a new problem in 2021: Sales are up, but many eateries do not have the staff to support the increased volume.

“What that causes is not the greatest experience for the customer and also not the greatest experience for our team members,” Lyons said. “They get spread thin, and they get burnt out as they’re working long hours to fill in gaps as best we can for being understaffed.”

Lyons is not the only business owner facing these challenges. While the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program ended June 26 in Texas, data from a March survey of 1,500 U.S. workers of different age groups, experience levels and industries by employment website Indeed shows employee burnout worsened over the last year with 52% of respondents feeling burned out and 67% believing the feeling worsened over the course of the pandemic.

Lyons said staffing challenges for restaurants may persist until job seekers feel more highly valued, though industry experts and other restaurateurs feel many restaurants are already doing what they can to put themselves on the path to recovery.

Brennan’s of Houston, a famous upscale New Orleans-style restaurant, has loyal employees but has struggled to retain newly hired employees since it reopened in spring 2020, owner Alex Brennan-Martin said.

“It has been an extraordinarily difficult period of time since then holding on to new employees no matter the benefits we offer, no matter the pay we offer,” he said.

‘Economically insane’

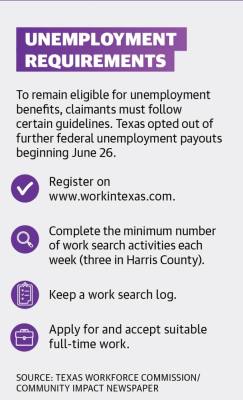

On May 17, Abbott announced Texas was opting out of federal unemployment compensation, focusing instead on “helping unemployed Texans connect with the more than a million job openings, rather than paying unemployment benefits to remain off the employment rolls.”

Critics of the move said the consequences are far reaching and it is economically unsound.

Jay Malone, political director for the Texas Gulf Coast branch of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations, the largest federation of unions in the U.S, said the decision by the governor makes no economic sense.

“The decision by the governor to reject billions of dollars in federal assistance was both cruel and economically insane,” he said.

In addition, any change to unemployment benefits has a massive multiplier effect, positive or negative, Malone said.

“We’ve seen benefits of the pandemic unemployment assistance on the economy,” he added. “When you look at where the money from unemployment goes, it goes to rent; it goes to food; it goes to child care; it goes to the essentials—all of which stays in the community.”

In late March, economists with Bank of America projected the federal unemployment stimulus would create a 7% improvement in the U.S. economy, up from prior estimates of a 6.5% growth.

Abbott also cited fraudulent unemployment claims as part of his decision to end the benefits. He referenced Texas Workforce Commission data for May 17 that estimated nearly 18% of all claims for unemployment benefits since the commission began tracking data March 1, 2020, were confirmed or suspected to be fraudulent with most instances being identity theft. That number was down to 14% on June 26, the TWC confirmed.

However, in the restaurant industry in particular, that trend does not play out, said Melissa Stewart, executive director of the Greater Houston Restaurant Association.

“Prior to the end of June, out of about 86,000 people in our greater area that were receiving unemployment benefits or had recently received them, only about 1,100 were from the hospitality industry,” she said. “The vast majority were more administration or office kind of work.”

Areas to address

Employees will return more readily to the restaurant industry when they feel more valued, and that comes partly through the restaurant’s culture and employee wages, Lyons said.

The COVID-19 pandemic also forced these employees to re-evaluate their options, he added.

“We’re losing candidates, and we’re losing existing people that have worked with us for a long time to Amazon and FedEx and other jobs and other industries. We’re not losing candidates to other restaurants, we’re losing candidates to other industries, and that’s a problem,” he said.

Amazon, for example, hired over 400,000 employees throughout 2020, bringing its worldwide workforce to nearly 1.3 million at the start of 2021, according to the company’s U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission annual filings.

With supply low and demand high, competition has driven employee wages up, said Joshua Santana, co-owner of Houston-based strategic consulting firm Cerboni Consulting and Financial Service. This was seen when national franchise Chipotle raised its hourly wages to an average of $15 per hour in June, joined by an average 10% wage bump by McDonald’s for its employees.

To help incentivize more employees, restaurants have resorted to measures such as sign-on and referral bonuses, Santana said.

“When there’s a high demand, people are going to ask for more because there is a limited quantity,” he said. “There’s also safety; there’s health, and people understand that.”

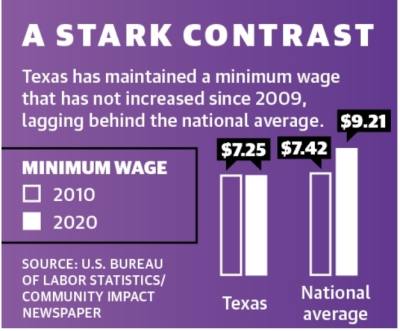

New measures like these have helped raise average hourly earnings for leisure and hospitality—which includes food workers—to $16.82 in May, according to preliminary data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. This is in contrast with the federal minimum wage of $7.25, a wage shared by Texas that increased from $6.55 to $7.25 on July 24, 2009, according to the TWC.

However, about 8% of leisure and hospitality workers nationwide earned hourly wages at or below the federal minimum wage in 2020, according to a February 2021 Bureau of Labor Statistics report. This did not include tips. And in Texas, 2.3% of all workers were at or below that line, about 143,000 total.

For these reasons, Malone believes any discussion about jobs and the economy should first start with workers and their financial needs.

“There are a lot of companies that tell you they can’t make things work if they’re paying their people more than minimum wage,” he said. “How does that serve our communities when you have tens of thousands of people that aren’t able to support their families?”

According to Stewart, the future of the industry remains bright as Houston communities continue their pandemic recovery. Meanwhile, restaurants have moved toward more efficient business models that utilize fewer staff.

“I think we start from a little bit of a deficit because we do hard work,” Stewart said. “However, we know time and time again, it can be overcome. For example, legacy restaurants have employees that have been with them for decades, and that doesn’t happen for no reason. The restaurants have created an environment where employees want to stay. So what we’re seeing is more and more attention brought to creating that longevity and setting up institutions where people will want to stay for a long time.”

Brennan’s, for instance, has done what it can to treat employees like family members, Brennan-Martin said.

“I have a captain in the dining room—a senior server—who has been with me for 47 years,” he said. “I have several that have been with me for more than 30, and a handful that have been with me more than 20. We have long focused on making sure our employees have very good benefits. We have always offered subsidized health insurance, paid vacations even for tipped employees and paid time off. We’ve gone out of our way.”

According to Lyons, however, there are still restaurants in the industry that need to re-evaluate themselves.

“I would encourage owners to look in the mirror and ask if they’re really creating an exceptional work environment that would draw somebody in or keep somebody from leaving,” he said. “I don’t think we’re there yet—I mean, I’m not even there yet. We could be doing so much better and we strive for that, but it’s very very difficult to do.”

Eva Vigh contributed to this report.