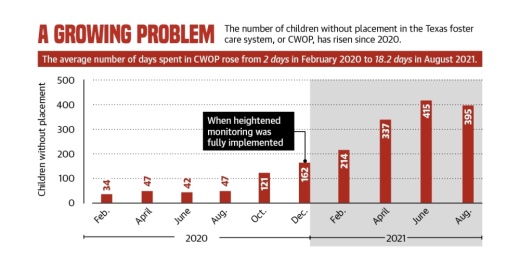

According to DFPS officials, individuals in the state’s foster care system receive a “child without placement” designation, or CWOP, when the state cannot find a suitable and safe placement for that child, requiring the DFPS to provide temporary emergency care until a placement can be secured.

Over the last two years, the state has increasingly relied on unlicensed placements—often motels or office buildings—overseen by caseworkers. In October 2019, 32 children were in such placements statewide, according to DFPS data. By August 2021, the most recent data available, that number had risen to 395 children.

Meanwhile, COVID-19 has caused a decrease in the number of foster families available to foster children, said Charity Eames, the chair of the Children’s Services Board of Galveston County and clinical director of DePelchin Children’s Center in Houston. The board provides oversight of county funds for foster children, and the children’s center provides children’s mental health, intervention and welfare services.

Foster families have not been immune to the financial hardships and illness brought on by the pandemic. This has caused many foster families to give up fostering, Eames said.

Eames said some of her fellow board members work with foster children and say that sometimes it is the children themselves who choose to be without placement. For instance, some CWOP are put into foster homes, and they repeatedly run away, Eames said.

“Unfortunately, sometimes the kids don’t want to be placed, so they cause trouble in the placements that are found for them,” she said.

Extenuating circumstances

In an August CWOP report, DFPS officials said the number of children designated as CWOP had risen, in part, because of heightened monitoring regulations mandated after U.S. District Judge Janis Graham Jack ruled in 2015 that foster children in Texas “almost uniformly leave state custody more damaged than when they entered.” Resulting system reforms included heightened monitoring, which is implemented when certain foster care system entities have had a high rate of violations.

Entities placed under heightened monitoring are given a plan by court monitors to address deficiencies and, failing that, face consequences, such as having their licenses revoked.

Since January 2020, 21 facilities with 13 or more children have been shut down or had their licenses revoked statewide, leading to the loss of about 1,200 beds, according to a September court update.

Rebecca Mercer, regional director of statewide adoption agency Lonestar Social Services, said heightened monitoring has also led to some foster parents removing themselves from the system altogether. She also said the pandemic has made finding placements more difficult.

“We’ve had a lot of foster parents that will come to us and say, ‘Until COVID is over, we’re not interested in taking placements anymore because it’s just too much,’” she said.

Arrow Child & Family Ministries, a Houston-area Christian nonprofit organization, is a partner agency that provides child welfare services to children and families throughout Region 6—which includes the Bay Area.

Officials at Arrow said the area has followed state trends; plus, CPS is no longer licensing adoptive families in Region 6, leaving the burden of licensing, hosting informational meetings and training prospective parents on local agencies such as Arrow.

Searching for solutions

The DFPS has identified a need for 669 additional beds throughout the state to meet growing demands on the welfare system. Additionally, the department said it is lacking an adequate number of CPS caseworkers with 236 vacancies statewide.

With these issues, Texas passed several pieces of legislation during the pandemic to address the needs.

State Senate Bill 1896, passed in May, revised and added regulations for the DFPS, including forbidding it from housing a child in an office overnight, expanding eligibility for therapeutic foster care and transitioning into electronic case management.

Additionally, the DFPS requested an additional $83.1 million as part of Senate Bill 1 to hire 312 caseworkers, which the Legislature fully funded, according to the September CWOP report. House Bill 5, which passed in September, allotted an additional $90 million to the DFPS, which will be used to retain providers and increase capacity to serve foster youth.

“The importance of this funding cannot be overstated,” said Melissa Lanford, the media specialist for DFPS Region 6. “It is the difference between a real placement for these older children and continuing to live in a CPS office or hotel.”

In the September CWOP report, DFPS Commissioner Jaime Masters said many providers have cited heightened monitoring as a reason for declining a placement, although she noted that did not indicate the department’s disapproval of the mandate.

“DFPS is not ‘blaming’ the [CWOP] crisis on the court’s heightened monitoring orders,” Masters said. “While the monitors have noted DFPS’ ‘collaborative’ efforts of listening to concerns of its stakeholders, it is an undisputed fact that DFPS cannot do this alone.”

She said caseworker turnover resulting from overworked employees has contributed to the growing number of CWOP. Between February and July, the DFPS hired 319 caseworkers, but 309 caseworkers left their roles during that time. Exit surveys in 2021 said 86% cited work-related stress as a cause for ending their employment, up from 40% in 2020.

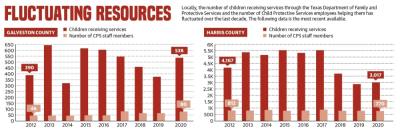

In Harris County, the number of children receiving DFPS services increased from 2,876 to 3,017 from 2019 to 2020. The number of CPS workers decreased, moving from 784 to 770.

In Galveston County, the number of children receiving services increased from 376 to 538 from 2019 to 2020, and the number of CPS workers moved from 67 to 80. Data for 2021 is not yet available.

Harris County commissioners at a Dec. 15 meeting unanimously approved the construction of a roughly $35 million Houston Alumni and Youth Center campus in downtown Houston that will include a 50-unit residential facility for youth transitioning out of the state’s foster care system. It also will include the HAY—Houston Alumni & Youth—Center, a program operated through the Harris County Resources for Children and Adults Department that provides resources and services for youth and young adults exiting the state foster care system. Construction will finish in late 2023.

Additionally, on Jan. 10, a panel appointed by Texas Gov. Greg Abbott as part of a lawsuit—M.D. v. Abbott—described Texas’ foster care system as “woefully inadequate” and recommended increasing mental health resources, improving guidelines and eliminating barriers to services.

Paul Yetter, lead attorney in the M.D. v. Abbott case, said he believed the state’s response was not enough to fix the foster care system’s ongoing problems.

“The state agencies’ pledge to collaborate with us and with each other could make a real difference for the children,” Yetter said. “That said, the state’s response falls far short. It fails to promise some of the most critical system changes needed by these vulnerable children, including efforts to improve kinship care operations.”

Laura Aebi and Danica Lloyd contributed to this report.