They are astronauts, and they spend their days at the Johnson Space Center in Clear Lake furthering NASA’s mission to explore space and eventually reach Mars.

But before astronauts ever strap into a rocket and blast off to the International Space Station, they must first spend two years in basic training as astronaut candidates followed by years of mission-specific training. Before that, they must be among the talented few NASA selects from a pool of thousands of wannabe space explorers.

In January, the latest group of astronaut candidates graduated and were officially added to the Astronaut Corps. This class of 11 was the first to graduate from training under the Artemis program, which is NASA’s designation for the manned spaceflight program that will land crews on the moon and Mars.

These unique individuals will spend years helping other astronauts with their missions before eventually being selected for missions of their own, after which they will spend years preparing, said John Charles, a Clear Lake resident and NASA scientist who retired in 2018.

“It’s glamorous, heroic, historic, and it’s also exceedingly dangerous to be an astronaut,” he said. “I cannot imagine a more exciting, challenging, rewarding and daunting career to have.”

'SPECIAL, DIFFERENT PEOPLE'

The open secret at Johnson Space Center is every NASA employee wants to be an astronaut. The reality, Charles said, is very few have what it takes to actually become one, and that is why Bay Area officials and residents often laud the Johnson Space Center, astronauts’ workplace, with pride.Since the 1960s, tens of thousands of Americans have applied to be astronauts. In over 50 years, NASA has selected only 350 for the job. With such a high bar for entry, only the best of the best are picked for the task, Charles said.

“The people they select are not world-famous test pilots or world-famous astronomers; they’re world-famous test pilot/astronomer/gourmet chef/concert pianist/brain surgeons,” Charles said. “NASA gets so many applicants they can afford to be extremely picky.”

In 2017, NASA received thousands of astronaut applications. Officials parsed through them all and picked out the few hundred that stood above the others. Applicants who made it this far in the process were already among the very best America had to offer, Charles said.

“You know, they’re all stellar, but some are more stellar than others,” he said of the applicants.

Eventually the group was narrowed to dozens who were called to come to the Johnson Space Center for several interviews and a physical.

NASA looks for several qualities in potential astronauts. They need to be able to handle danger without being risky. They need to be no-nonsense leaders but also obedient followers. And they need to be lucky, even though luck does not exist in the aerospace business, Charles said.

“They want people who have shown they know how to live on the edge but not be foolish about it ... because that’s what this is all about,” he said.

Of the 18,300 who applied three years ago, only 12 Americans were selected for the most recent round of astronaut candidate training.

These selected few moved to the Bay Area, reported to the Johnson Space Center and became official astronaut candidates. Then the real work began.

Clay Anderson, a League City-based astronaut who retired in 2013, knows well the challenge of becoming an astronaut. He applied 15 times for the appointment, and he was eventually selected with 24 other Americans from a pool of about 4,600 applicants, he said.

“To apply that many times and to finally find success was pretty thrilling,” he said.

There are not many jobs that have a specific pathway to becoming an astronaut. Instead, those who end up becoming astronauts realize they have the skills, intelligence, motivation and work ethic necessary for the job and apply, Charles said.

“Astronauts are supremely self-confident, supremely self-motivated, and that’s why they do so many things. To be an astronaut, you’re not shy; you’re not uncertain of yourself,” he said. “We like to think it’s people off the street, but it’s not. They are special, different people.”

MOON AND BEYOND

As NASA has set its sights on returning to the moon and traveling to Mars, the space agency in recent years has begun training larger classes of astronaut candidates for space missions.The Johnson Space Center is working to return to the moon in four years. Because it takes two years for astronauts to complete basic training and training is not done every year, class sizes have increased, Charles said.

Additionally, more women are being trained. Traditionally, about 1 in 6 astronaut candidates were women. Now, the ratio is closer to 50-50, he said.

Of the Astronaut Corps’ 48 people, 16 are women, and one of them will make history in the next few years as the first woman to walk on the moon, Charles said.

“She’s here,” he said. “Any of those women will be candidates.”

Because the most recent astronaut class includes people who may go to the moon, their training had a larger concentration on working and living on the lunar surface, which is why they spent time training in geology and other related fields, Charles said. For instance, the class visited and studied a meteor crater in Arizona.

“They go off and do geology training, which is something they didn’t do during the shuttle and early space station [eras],” he said. “It really hearkens back to Apollo astronauts going off to craters and deserts and things like that learning to do geology on the moon.”

Of course, the moon is just a stopping point for NASA’s ultimate goal: Mars. NASA hopes astronauts will reach the red planet in the 2030s, and those who live and work in Clear Lake today could be among those selected for that historic mission.

“Thank God we have astronauts because we can pick the cream of the cream of the crop, and they will deliver every time,” Charles said. “They’re a tremendous resource that I don’t think people really appreciate.”

BASIC TRAINING

Astronaut candidates undergo two years of basic training, and most of it happens at the Johnson Space Center.Astronaut candidates learn everything from survival skills to the correct way to don a space suit to how to live and work on the ISS, the moon and Mars. Astronaut candidates also spend a lot of time aboard T-38s, which are supersonic jets, to learn how to handle high G forces, said Ken Cameron, an astronaut who retired in 1996.

Kaci Heins, the director of Space Center University, a part of Space Center Houston dedicated to educating the public about space exploration, said astronauts have to learn even relatively simple tasks, such as how to escape from a crashed helicopter, before they can start flight school. Unlike space shuttles, capsules that return to Earth from space can land anywhere, so astronauts are grateful for such training because emergencies can happen anytime and anywhere, Heins said.

“If your capsule, when you return to Earth, lands somewhere you didn’t plan on, you have to be able to survive in those different situations, whether it’s on land or it’s on water,” she said. “Astronauts must be prepared for everything.”

Jim Fuderer, a safety instructor with Bastion Technologies, a company that, in part, helps train astronauts, said astronaut candidates spend hours sitting in capsules and learning how to enter and exit the capsule safely and then enter a helicopter to fly home. Apollo-era astronauts who returned from the moon were the last astronauts to use capsules, but they will make a comeback in the form of Orion as NASA returns to the moon, making the training important, he said.

“[Astronaut candidate training] is really learning systems, learning Russian, learning where your office is and where the bathroom is,” Charles said. “It’s just taking someone that’s totally naive and making them minimally qualified to fly in space.”

American astronauts learn Russian so they can more easily communicate with Russian crews. Today, astronauts must launch from Russia to reach the ISS, though that could change soon with commercial space companies that would allow American astronauts to reach the ISS aboard American-made and -launched rockets, Charles said.

“I would say it’s not necessarily difficult training, but there’s a ton of things you’re exposed to with the expectation you’ll maintain some recollection of what you’re exposed to when you need it in space,” Anderson said.

Building 9 of the Johnson Space Center is the Space Vehicle Mockup Facility, which includes a full-scale mockup of the habitable modules of the ISS. Astronaut candidates spend a lot of time in this building learning the ins and outs of the International Space Station, a spacecraft governments around the world use for zero-gravity science experiments and research, Charles said.

“The astronauts have to understand all the components on all the systems. So even though you can’t float into [the ISS mockup] like you can in weightlessness, they have to go inside there and know where the connections are and the switches are that they have to be adjusting and maintaining,” Charles said.

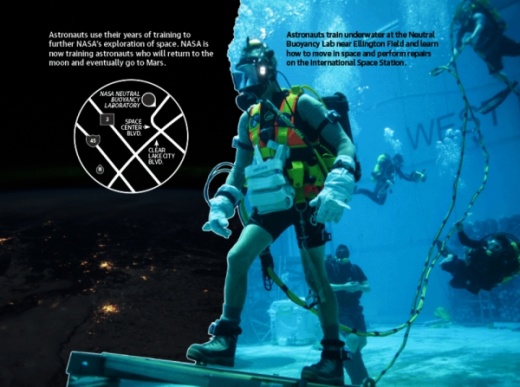

Another popular training spot is the Neutral Buoyancy Lab near Ellington Airport north of the Johnson Space Center.

The lab comprises a 40-foot-deep pool that contains a second full-scale replica of the ISS underwater. Astronaut candidates are put into space suits filled with lead weights and then lowered into the water. The weights are adjusted until the candidates become neutrally buoyant, which means they neither sink nor float, to simulate the weightlessness of space. Astronaut candidates will spend up to eight hours in the lab practicing maneuvering through the ISS and performing simulated spacewalks where they move components of the space station around and do mock repairs.

“This is not [a] vacuum. It’s high resistance, very viscous fluid, so it’s best for training slow—a low-range process,” Charles said. “If you wanna practice moving big things that have to move very slowly, then it’s a great place.”

For weightlessness training, astronauts can board a reduced-gravity aircraft, or “vomit comet,” that flies high and then free falls, making those aboard weightless for a few seconds at a time. Between that, Building 9, the Neutral Buoyancy Lab and other locations, there is redundancy in astronauts’ training.

“It’s really piecemeal training to do what you need to do as an astronaut in a spaceflight,” Charles said. “That’s another reason it takes so long is because you’re doing everything sort of three different ways.”

MISSION TRAINING

After completing basic training, astronaut candidates graduate to NASA’s official Astronaut Corps. They are then eligible for assignment to missions to the ISS, the moon and Mars.Astronauts are initially selected to be a backup crew member for a mission. They train alongside the primary picks for the crew, which can be another two-year cycle of mission-specific training, Charles said.

After being a backup for a mission, an astronaut is typically then assigned as a primary crew member for a mission. They spend a few months brushing up on any skills they need and then spend up to months at a time in the ISS doing experiments, making repairs and completing other tasks.

The two retired astronauts Community Impact Newspaper spoke to said the basic and mission-specific training they experienced in the Space Vehicle Mockup Facility, the Neutral Buoyancy Lab and elsewhere all came in handy during their stints in space.

Cameron went on three shuttle missions in the 1990s. He arrived at the Johnson Space Center in 1984 but did not fly until 1991.

In between, he and other astronauts were trained in specific areas in which they would be working during a shuttle mission, such as how to pilot the shuttle, how to operate its robotic arm and more. Astronauts also were trained in what their fellow crew members learned so there was an understanding of each other’s jobs, Cameron said.

“That helps bring the team together and teamwork within the cockpit,” he said. “You have to mentally understand [the shuttle] so you can fly it without thinking about it.”

Cameron learned a lot in classroom settings and also received training on how to do spacewalks in water. Cameron never did a spacewalk, but the training he received to help others into their space suits helped him prepare fellow crew members for their spacewalks, he said.

“You train for a while as a full-time job, and pretty soon you wind up having ... collateral duties and secondary jobs,” he said. “There’s a body of knowledge that they’re trying to pass along, and it’s paved so you’d be ready to fly quickly.”

Anderson joined NASA in 1998 and first flew to the ISS in 2007. In between, he underwent 3 1/2 years of training.

Trainers tried to teach astronauts basic skills that they could apply to other situations. Anderson compared it to a father teaching his son how to change a car tire in hopes he could also apply those skills to changing a bicycle tire if necessary.

“The folks that train you are so dedicated, and they bust your hump to give you what they need,” he said.

Being an astronaut is a huge commitment, Charles said. The training takes years, and when astronauts are not at work, they are at home studying or memorizing huge manuals of how to operate machinery. Missions result in astronauts being away from their families for half a year or more, but to astronauts, it is worth it.

“Even if you’re not flying, being an astronaut is one of the coolest jobs on Earth,” Charles said. “Why would you go anywhere else?”