A large portion of the online museum focuses on the Douglass Community, a historically Black neighborhood in downtown Plano.

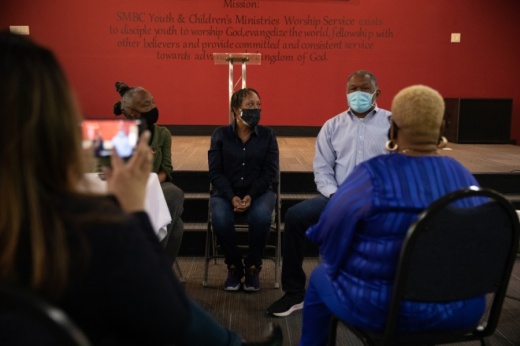

Much of the Douglass Community’s history is pieced together by the few photos, texts and objects available about the people who lived there, according to Cheryl Smith, a Plano Public Library genealogy librarian. Zara Jones, a Plano West High School senior, said she has committed to moving what exists of this history to an online museum in the form of six exhibits and oral histories as part of her Girl Scout Gold Award project.

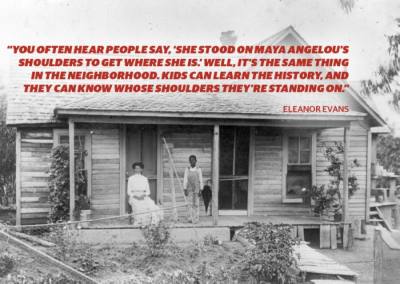

This digital effort aims to educate residents of Plano about where they came from, said Eleanor Evans, a descendant of the Stimpsons and Drakes, two of the earliest Black families to settle in the area. If even 10 children learn their history, that would be progress, Eleanor said.

“You often hear people say, ‘She stood on Maya Angelou’s shoulders to get where she is,’” she said. “Well, it’s the same thing in the neighborhood. Kids can learn the history, and they can know whose shoulders they’re standing on.”

The land on which the Douglass Community sits began as a plot of land owned by Joseph Klepper, one of the earliest known landowners in Plano.

A portion of Klepper’s land along US 75 and to the south of 15th Street was largely settled by Black families in the late 1800s, according to the “Douglass Area Study,” a work prepared by the city of Plano in 1990. The study also documented a segregated school built in the neighborhood in 1896.

The area got its name as early as the 1950s, when the school was rebuilt as Frederick Douglass Elementary School, named after the famous abolitionist. The school later became the Douglass Community Center and now operates as the Boys and Girls Club of Collin County.

Eleanor, who was born in 1940, was raised in the Douglass Community. She said she remembers attending the segregated school and being taught the importance of education and religion by her family.

She also said she remembers being happy growing up with so little, a feeling that shifted when the Douglass Community was integrated.

“We didn’t know we were poor,” Eleanor said. “But once integration came along, we got to see some stuff that some other people had.”

Sisters Dollie Thomas and Toni Thomas and cousin James Thomas III—grandchildren of James “Jim” Lawrence Thomas, the patriarch of another integral family of the Douglass Community—were part of the first generation of Black students integrated into Plano ISD. There were definitely moments of hardship—the memories of which still bring Toni to tears, she said—but Plano was integrated more smoothly than many Southern cities, the Thomas cousins said.

A number of key players helped create greater change in the school district, such as Coach John Clark, who helped Alex Williams become Plano High School’s first Black starting quarterback in 1965, and the work of John F. Hightower, who was principal of the segregated school before working with the district. The city honoring Black Plano residents through the naming of buildings, including Thomas Elementary School in 1979, also helped.

“The city of Plano felt that it was important to have something in this man’s legacy because of all the things that he did, not just for his neighborhood but also for the white neighborhoods as well,” James said of his grandfather.

Over the years, many former Douglass Community residents have moved into new areas of Plano. But the spirit of the neighborhood remains alive and well in the minds of those closest to it, the Thomas cousins said, and generations of founding members have said they are working to keep it that way.

“We have to help this community remain the rich fabric of our lives that it has always been,” Toni said.