District 1 Council Member La’Shadion Shemwell is facing a recall election nearly three years into his four-year term, but a federal lawsuit filed by Shemwell against the city could derail that effort.

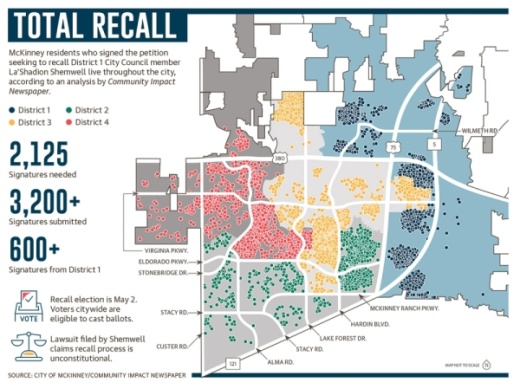

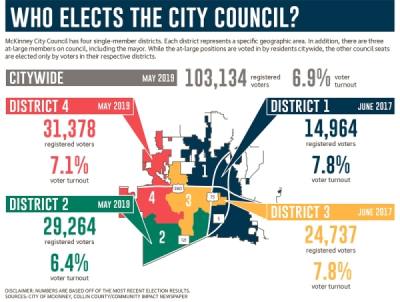

Shemwell was elected to represent District 1, which stretches along the city’s east side. But the recall process in McKinney mandates that voters citywide get to weigh in on his fate.

The lawsuit claims that the City Charter is unconstitutional because it dilutes the votes of District 1 residents by allowing the entire city to vote in the recall election.

McKinney Mayor George Fuller said he believes the recall election should be citywide.

“His actions do not just impact the district,” said Fuller, who supports Shemwell’s recall. “They impact every single taxpayer in this city.”

The suit seeks to halt the recall process and declare portions of the McKinney City Charter unconstitutional.

“Single-member districts were formed to protect rights of minorities, so that they may be allowed to have their chosen representatives,” Shemwell’s attorney Shayan Elahi said in an email. “Council Member Shemwell is suing the city of McKinney for ‘voter dilution’ under the Voting Rights Acts of 1965 and 1973.”

Single-member districts were first created in McKinney in 1977 through a charter election. The 2010 Census showed less than 50% of residents in District 1 were white, making it a minority-majority district, according to the city attorney. Results from the 2020 Census will determine whether that is still the case, City Attorney Mark Houser said.

“This is voter suppression 2020,” Shemwell said in a Facebook video posted Jan. 22. “They are taking away the [voices] ... in District 1 to vote for who they want to represent them.”

Fuller said he believes Shemwell’s lawsuit represents a “failure to take responsibility for his actions.”

Elahi said Shemwell hopes to have the recall election limited to District 1 voters so that only the people who elected him will decide whether he stays in office.

If the suit is unsuccessful, Shemwell said he will run an “all-out, citywide campaign.”

According to Elahi, a hearing is scheduled for March 30.

“The judge will decide whether the city of McKinney has violated the Constitution by being dismissive of the Voting Rights Act,” Elahi said in the email.

Recall on the ballot

The recall process was triggered by a citizen-initiated petition that received more than 3,100 signatures from registered McKinney voters—nearly 1,000 more than needed.

The petition claims Shemwell “has not upheld his oath of office, has violated the City Charter, has disregarded the City of McKinney Code of Ethical Conduct [and] has not appeared at meetings and events at which he agreed to represent his constituents.” The recall petition also alleges that Shemwell “made inflammatory statements about residents and staff of the city of McKinney.”

Shemwell had the option to resign from office after the petition was certified. He chose instead to proceed with the recall election.

“I will fight with every breath in my body,” Shemwell said at a council meeting. “What is the point of having a First Amendment right to speak if I cannot use it?”

The petition began circulating last year shortly after a series of contentious McKinney City Council meetings were dominated by racially heated conversations.

The most notable meeting took place Oct. 15 when Shemwell suggested the city declare an official “Black State of Emergency” in Texas after two black residents were killed in their homes by police officers in Dallas and Fort Worth during separate incidents.

During the October meeting, Shemwell said, “The state of Texas and its local governments have declared war on black and brown citizens by conspiring to kill, injure, oppress, threaten, and intimidate, and to willfully deprive citizens of their constitutional rights while acting under color of law.”

This statement led to a separate ethics complaint filed by a citizen alleging that Shemwell’s statement violated the city’s “code of ethical conduct in that it alleges criminal conduct by local and state officials.” That complaint is currently under review by a third-party attorney.

Shemwell’s comments have also drawn residents from outside

McKinney to recent council meetings. His supporters recounted personal experiences of racial prejudices and brutality from police officers.

“This isn’t a state of emergency here. This is a state of emergency everywhere,” said Dee Crane, an Arlington resident whose son was killed by an Arlington police officer in 2017. “Mothers like me are suffering in silence, and nobody seems to care except for him.”

Others have criticized some of Shemwell’s controversial statements as well as his conduct.

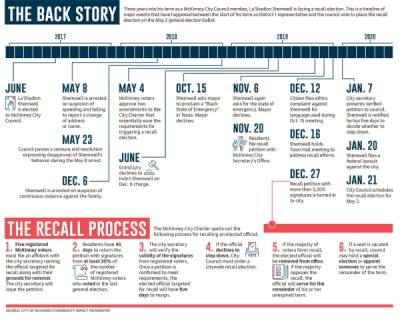

Shemwell was arrested in December 2018 on suspicion of continuous violence against the family. A grand jury declined to indict him on the third-degree felony charge. He was also arrested earlier that year on suspicion of speeding and failing to report a change of address or name, according to county records.

Shemwell “displayed uncooperative and argumentative behavior” during that traffic stop and directed the officer to contact his department head, according to city documents.

Shemwell told City Council that he should have handled that situation better, but he voted along with the majority of council to approved a censure and resolution expressing disapproval of his behavior.

Fuller said discussions about Shemwell’s potential recall began after the first arrest.

“This has nothing to do with his color,” Fuller said. “It is about character.”

Charter changes

This petition is the first in McKinney’s documented history to trigger a recall election, according to the city.

The recall election comes less than a year after voters approved changes to the City Charter. Those changes ultimately made triggering recall elections easier by decreasing the number of signatures needed and increasing the time frame during which petitions can circulate.

After the changes, residents now have 45 days to turn in signatures to the city secretary. The previous charter gave residents only 30 days.

The charter also requires signatures from at least 30% of the number of voters who cast ballots in the last regular municipal election. As more than 7,080 voters cast ballots in the May 2019 election, the petition needed at least 2,125 signatures to be valid, according to the city secretary’s office.

Under the previous charter, signatures were needed from at least 25% of the total number of voters who cast ballots in the last municipal election, provided that the petition contain signatures of at least 15% of registered voters in McKinney. With more than 103,130 registered voters in that last election, petitioners would have been required to gather nearly 15,500 signatures to trigger a recall, city officials stated.

These were the first changes to the City Charter related to recall petitions since 1959, Houser said. Last year’s charter amendments also clarified that recall elections remain citywide, he said.

What is next

On the May 2 ballot, voters will be asked: “Shall La’Shadion Shemwell be removed from the office of McKinney City Council Member (District 1) by recall?”

If the majority of votes cast are against the recall, Shemwell will remain in office for the rest of his term, which expires in May 2021. But if the majority of votes are in favor of his recall, he will be removed from office.

Council would have the option to fill the vacancy by appointing someone to serve the remainder of his term. Council could also decide to hold a special election, which would be held Nov. 3, Houser said.

“The citizens are in charge of the recall,” Houser said.