Protest organizer Sarah Edwards said she was spurred to join the multitudes of people across the country speaking out against the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police after a simple comment from her 13-year-old daughter. “That could have been my friend,” her daughter said.

The protest that day turned into another and another. By the 11th day, there had been more than 1,200 people on that corner. They, along with hundreds of others across Lewisville, Flower Mound and Highland Village, have come together in recent weeks to make their voices heard as part of the national movement against racism and police brutality.

But here in the suburbs, protests have mostly run their course, and what comes next will be key, some local protest organizers said.

“We’re trying to keep [these issues] at the forefront of everyone’s minds,” said Juan Coronel, organizer of two Highland Village protests. “Everything has a route back to this problem everywhere in our society.”

The goal, organizers said, is to keep the conversation going in ways that will make the most impact.

“Everybody has a di fferent role to play in this movement,” said DaShantanaya Lee, one of the Lewisville protest’s four organizers. “Mine is ... to use my voice to my advantage because I know people are going to listen to it.”

Combating misinformation

Lee’s voice was one of many that brought calm back to a frightened and angry crowd of roughly 350 people marching in Lewisville on June 2.

The protesters had peacefully marched from Lewisville High School to Wayne Ferguson Plaza downtown, where speakers shared their thoughts and stories with the crowd.

On their way back to the high school, Lewisville police said, a drunken man ran into oncoming tra ffic and knocked over a woman and child. As officers moved to arrest him, protesters mistook him for part of their group and started throwing objects, police said. After issuing multiple warnings, police released tear gas into the crowd.

Eight additional people were eventually arrested on suspicion of resisting arrest, assaulting a police o fficer or obstructing a roadway, according to police. The rest of the crowd was met by Lewisville Police Chief Kevin Deaver, who, with the assistance of Lee and the other organizers, calmed everyone

down.

The city released a lengthy report on the situation, and Deaver met the next day with the event organizers to set the record straight about what happened. The resulting video, called “Talk with Chief Deaver,” was also released online to combat any misinformation.

“For the most part, I think that people understand the situation better now,” Lee said. “It just got a little bit out of control, and as unfortunate and as saddening as that is, we have addressed it. ... And we will continue to talk about it, if that’s what’s going to make people feel comfortable.”

Policies for policing

Following Floyd’s death in May, Lewisville, Flower Mound and Highland Village police departments shared varying statements condemning the actions of the officers involved.

Flower Mound Chief Andy Kancel called the police actions leading to Floyd’s death “horri ffic.”

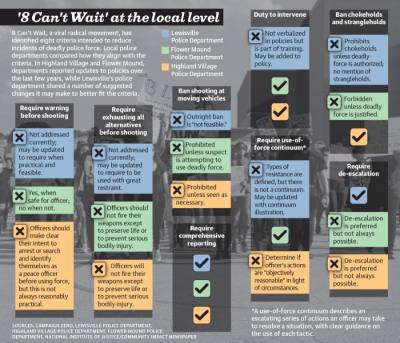

Highland Village and Lewisville departments also publicly shared how their policies compared with the viral 8 Can’t Wait project, which was created by nonpro fit group Campaign Zero to encourage immediate change in policies that could reduce police killings.

Highland Village stated that its use-of-force policies have been revised roughly eight times since their creation in the late 2000s. In addition, the department conducts an annual review of its policies in accordance with the Texas Best Practices requirements, a voluntary program for law enforcement agencies to prove their compliance with more than 100 standards and policies developed by Texas law enforcement professionals.

In Lewisville, the department reviewed its policies and shared adjustments that might be adopted in the future but had some concerns about the 8 Can’t Wait recommendations.

Their biggest concern was the outright ban of certain policies meant to be used only in situations of deadly force. This was also given by Highland Village and Flower Mound police departments as the reason for many policies not fully matching the 8 Can’t Wait recommendations.

The complete ban of certain policies is why the 8 Can’t Wait platform self-identi fies as a “radical transformative” campaign on its website.

In Flower Mound, use-of-force policies have been in place for a long time but have received minor revisions to be more speci fic and to fall in line with Texas Best Practices, according to Capt. Shane Jennings. These changes largely a ffected verbiage and consistency with other departments, but the practices have remained the same, he said.

Continuing the movement

When Coronel reached out to the Highland Village Police Department about its policies, he said he was told it was not a place where Black people are killed.

“It might be, just not yet,” Coronel said. “We’ve seen it in many cities—small cities, large cities—but it’s really about these bigger policies that are going on across the United States.”

As a person who lives outside of Highland Village but works there, Coronel said he thinks it is important to show people their privilege so that they can enact change in their communities.

Holding two protests was a start to that, he said, but shifting into education is next. Coronel said he is currently working on a plan for Black and minority voices to be part of a speaker series.

Edwards said she is taking steps to educate herself as well as to find ways to educate others, especially children. A Denton County race relations committee, now in its infancy as a private Facebook group among like-minded friends, may also become a reality at some point, she said.

“I think that’s probably the key is educating younger ... students,” Edwards said. “And there probably needs to be some reform in the way that history is written.”

Education is also an important step when it comes to voting, Lee said. After passing out voting information at the June 2 protest, she said she has continued conversations with Lewisville City Council, change-oriented organizations in Dallas and other prominent figures, as well as with the public on social media.

“The fight is not over,” Lee said. “Even though your social media posts might look like life is going back to normal and your friends may have stopped talking about it, I haven’t stopped talking about it. And my friends haven’t stopped talking about it.

“We’re going to keep talking about it. And we’re not going to go anywhere.”

Correction: Roughly 1,200 people came to the Flower Mound protests over the course of 11 days.