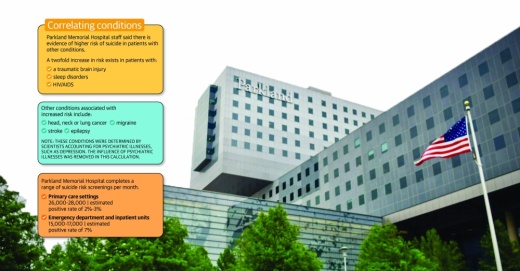

According to Parkland Health data, anywhere from about 41,000-45,000 screenings are conducted each month between its primary care and emergency departments. Positivity rate of suicide risk is typically around 2%-3% in primary care settings and around 7% in the hospital.

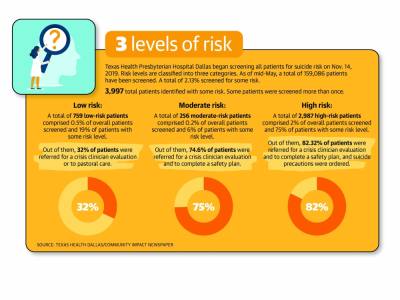

Parkland began screening all patients for risk of suicide using standardized and validated tools developed by the National Institutes of Mental Health in 2015, according to representatives from the hospital. At another hospital, officials with Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas said universal screening began in 2019.

Dr. Kimberly Roaten, director of quality for safety, education and implementation in the Department of Psychiatry at Parkland, said the screening program allows doctors to better identify individuals who are potentially at risk. Simply going through the screening may even reduce risk of suicide, she added.

“We opted to screen everyone [and] ask everyone these questions to try to catch more people,” Roaten said. “There are a number of benefits to it.”

An open dialogue

Roaten said Parkland has seen “a lot of attention” over the past seven years as it was the first major hospital system nationwide to implement a universal screening program.

Ahead of the program, Parkland officials found that many patients who die by suicide have contact with a health care system in the months prior to death. A Parkland news release from September 2016 stated that 77% of people who die by suicide had contact with a primary care provider in the year prior to death, and 40% had contact with an emergency department provider.

“We’re able to identify patients [and] individuals who are potentially at risk who we might otherwise miss,” Roaten said.

Parkland patients who are identified as being at risk of suicide then receive a full risk assessment, according to Roaten. Patients who are identified to be of high risk receive attention to “promote immediate safety,” including counseling and limited access to means of self-directed violence. In rare instances, Roaten said patients may be hospitalized.

According to Roaten, screening for suicide risk has not disrupted hospital workflow, nor has it upset patients and families. More hospitals on a local and national scale have become open to the idea of expanding suicide screening practices, she said.

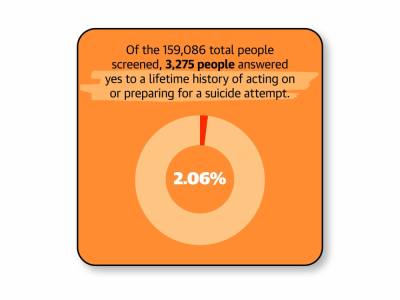

At Texas Health Dallas, a total of 159,086 patients as of mid-May had been screened for risk of suicide since universal screening began. Just over 2% of patients screened during that time indicated some risk of suicide.

Dr. Gonzalo Perez-Garcia, a psychiatrist with Texas Health Dallas, said asking patients if they are considering death by suicide does not plant the idea in their heads.

“There’s this misconception sometimes by the general public that it’s not safe to ask someone if they’re suicidal,” he said. “Studies have shown that is absolutely not true. It is very safe to ask someone if they’re suicidal.”

Patients at high risk for suicide at Texas Health Dallas are evaluated by a social worker to determine whether they need to be referred to a clinic or admitted to a hospital, Perez-Garcia said. In some cases, patients at Texas Health Dallas attend a group therapy program.

Perez-Garcia said open dialogues with friends and family can also help save lives.

“[Asking allows] someone who is suicidal to know that a friend or family member cares about them, worries about them and is a safe person to turn to in case thoughts are present or thoughts get worse sometime in the future,” he said.

Outside factors

Calls to crisis hotlines and emergency department visits for suicide-related risk factors have increased throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, according to Roaten. The full effect of the pandemic on suicide deaths is unknown due to a lag in data collection, she said.

However, she said expanded telehealth capabilities and awareness of mental health are benefits that came from the pandemic.

“I hope that we’re making a dent in the mental health stigma,” Roaten said. “I hope that by having these conversations and talking about how the risk has increased during the pandemic [it] is increasing the chances that people will be more willing to seek mental health care.”

Worsening depression is the No. 1 factor to identify when assessing suicide risk, according to Perez-Garcia. But officials with both hospitals said that a number of health conditions other than psychiatric illnesses could indicate a higher risk of suicide.

Texas Health Dallas staff members said chest pain is a nonpsychiatric complaint seen most commonly associated with suicide. Parkland staff also said that a number of conditions that may indicate a higher risk of suicide, according to scientific literature. They include certain cancers and conditions with chronic pain.

“Patients with chest pain ... that is the most common physical symptom of patients who mentioned being suicidal,” Perez-Garcia said. “I think that’s something to follow up on. ... That was certainly an interesting thing.”

Supporting students

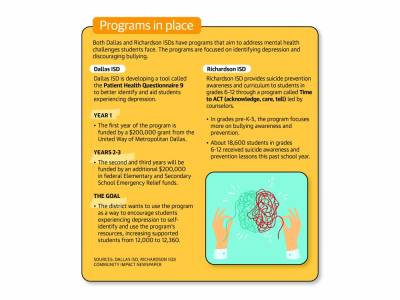

Programs to identify and assist children experiencing depression or risk of suicide are in place in the Dallas and Richardson ISDs.

This fall, Dallas ISD plans to debut a new tool called the Patient Health Questionnaire 9, or PHQ9, to better identify and aid students in grades 6-12 experiencing depression. For the 2021-22 school year, Tracey Brown, DISD executive director of mental health services, said the district has seen more than 10,000 student referrals for depression, isolation or anxiety.

GreenLight Credentials is working with the district to develop an app that allows students to answer questions related to interest levels and emotions, Brown said. Consent from parents will be required, Brown said.

The first year of the program is funded by a $200,000 grant from the United Way of Metropolitan Dallas. The second and third years will be funded by an additional $200,000 in federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief, or ESSER, funds. ESSER funds are federal grants designed to help overcome the adversities created by the pandemic.

The district wants to use the program as a way to encourage students experiencing depression to self-identify and use the program’s resources, according to a DISD statement.

“We recognize our role in helping students to be able to thrive in the learning environment,” Brown said. “We align what we do with the vision of our district, which is to ensure that all students succeed and they’re able to do that. And we know that if they’re suffering from a mental health concern, they’re not able to thrive in the classroom.”

Brown said the PHQ9 will assess the severity of depression in students. DISD officials will then determine whether a child is in immediate need. Students experiencing depression of low to medium severity could be connected to licensed clinicians and psychiatrists at a youth and family center provided by Parkland.

Richardson ISD provides suicide prevention awareness and curriculum to students in grades 6-12 through a counselor-led program called Time to ACT, which stands for acknowledge, care and tell. In earlier grades, the program focuses more on bullying awareness and prevention, RISD spokesperson Tim Clark said.

About 18,600 students in grades 6-12 received suicide awareness and prevention lessons this past school year, according to Clark.

Margie Wright, executive director of the Suicide and Crisis Center of North Texas, said a focus in her 20 years with the organization has been improving efforts to help at-risk children.

The Suicide and Crisis Center of North Texas offers a free 24/7 hotline that is staffed by trained volunteers. In addition, the crisis center coordinates with area schools to educate parents and staff on warning signs. The center also screens children for risk of suicide.

“People don’t generally tell people about their feelings,” Wright said. “People flippantly make remarks about suicide, but [others] don’t take them seriously. With the screening for us, the young people reveal things that they wouldn’t do face to face.”

Typically, around 15,000 students in school districts in the North Texas region are screened by the organization each year, according to Wright. She said, despite what year children are screened, a total of around 10% show some kind of risk.

Not enough resources are in places to help children experiencing mental health obstacles, Wright said. The crisis center recommends reduced-cost counseling for clients, but Wright said more funding needs to be invested by lawmakers, and mental health needs to be taken more seriously in the U.S.

When screening children, Wright said her organization is observing how children handle stress. She said larger events, such as a divorce in the family, may lead to more risk of suicide, but she added that occurrences, including bad grades or not making a sports team, may lead to difficult thoughts.

“Those don’t sound big ... [but] it doesn’t have to be anything that you or I would think of as a life event,” Wright said. “Things that don’t seem that big are pretty big at times. So you have to be aware of all that.”

Editor's note: This article has been updated to clarify that Parkland Health collected data from screenings for risk of suicide.