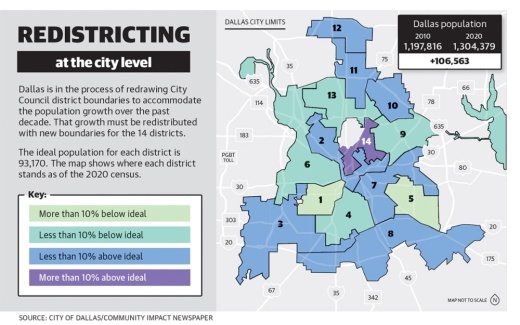

Known as redistricting, the process ensures that all 1.3 million Dallas residents are equally represented by City Council.

Last year, the council appointed a 15-member redistricting commission to sort through options and present a recommendation for new boundary lines to council.

Attorney Brent Rosenthal, who represents southern Lakewood as part of District 9 on the commission, said City Council members decide issues that directly affect the day-to-day lives of residents and urged citizens to engage with the process.

“Having strong City Council representation can make the difference [in] having roads repaired, having adequate sanitation services [and] having parks located in appropriate areas,” he said. “While it’s not as glamorous as the state legislature or federal government, it probably has more of an impact on quality of life than those in Austin or Washington, D.C.”

As Dallas’ population grows, so too does the population of individual council districts. To ensure that residents are represented equally, the Redistricting Commission must follow several guidelines.

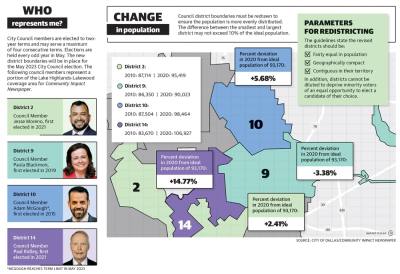

Among them are not splitting up neighborhoods when possible, making council districts geographically compact and not depriving minority voters of fair representation by way of gerrymandering.

Residents are not only able, but are encouraged to participate in the process through attending public meetings, offering feedback, and submitting their own district maps for consideration. The deadline to submit a map to the commission is April 15.

“The whole purpose of redistricting is to create districts that are representative of the neighborhoods and communities within the city so that we aren’t fracturing communities between multiple council districts,” Ridley said.

While Ridley and other City Council members strongly advocated for residents to participate in the redistricting process, a 2014 amendment to the city charter limits their ability to discuss the process in detail. That amendment also prohibits City Council members from having any direct or indirect discussions with commission members outside of public meetings.

By the numbers

Dallas’ population grew by nearly 9% from 2010-20, from roughly 1.2 million to 1.3 million. Back in 2010, the ideal size for a single district was 85,558 residents. Today, that number is 93,170.

The Lake Highlands and Lakewood areas are mostly represented by districts 9 and 10, though are also partially represented by districts 13 and 14, respectively. Collectively, these four districts hold about 386,575 residents.

Based on the 2020 census, District 14 saw the most growth, increasing from 83,670 residents in 2010 to 106,927.

Represented by Ridley, District 14 will have to shrink through the redistricting process. Exactly how its lines will be redrawn, however, will in part be a result of community input, something Ridley urged his constituents to provide.

District 10, where most of Lake Highlands is located, had about 98,464 people, which was also above the ideal population size. District 10 City Council Member Adam McGough also urged his constituents to help shape the district for the next decade.

“This influences your representation, so now is the time to really pay attention and make sure that neighborhoods are held together,” McGough said.

District 9 on the other hand, which includes Lakewood and beyond, had about 90,023 people, meaning the district could possibly expand. District 9 City Council Member Paula Blackmon said she believed that beyond increasing voter turnout, council districts that keep communities whole can also make allocating city funds a smoother process.

“When we get bond dollars or when we get any kind of budgetary items, it’s easier to allocate if you have one person looking over that [district],” she said.

“When you have two people or it’s divided, it waters it down and [becomes more difficult].”

Keeping communities together

One of the key priorities of the Redistricting Commission is keeping neighborhoods, communities and other organizations intact and within the same council district. Where exactly those lines are drawn, however, is often a challenge given the arbitrary nature of deciding where a community ends and a new one begins.

That ambiguity, Ridley said, is precisely why he urged residents to have their voice heard in the redistricting process.

“What’s most important to me is that we have a district that has complete communities of interest in it without fracturing communities of interest and neighborhoods with adjoining districts,” Ridley said.

Beyond neighborhoods, a litany of other factors are considered when drawing district lines, including school attendance zones, homeowners associations and more.

“We like to maintain our boundaries to follow major thoroughfares and not necessarily cut through neighborhoods,” said Jesse Oliver, chairman of the Redistricting Commission. “It takes effort.”

One citizen who has submitted three maps for consideration is Melanie Vanlandingham, a resident of Lakewood who regularly attends Redistricting Commission meetings at Dallas City Hall.

“To make meaningful changes for our new map, we must keep together important neighborhood associations, and the relationships to each other and each district,” Vanlandingham said.

“These reflect essential district characteristics built over decades about everything important to residents, leaders and businesses.”

Vanlandingham pointed to her own District 14 as an example, saying that the Lakewood community is directly tied with the Oak Lawn community as they’ve “developed in similar patterns over a hundred years.”

Another Dallas resident who submitted maps to the commission is Bell Betzen, who also participated in the 2011 redistricting process.

Betzen said that holding city leaders accountable for the redistricting process is essential to a healthy community.

“You want a city that works politically, and if the people are politically involved and watching their politicians, you’ll have more honest politicians and politicians that really are motivated to serve their people,” Betzen said.

How to get engaged

The Dallas redistricting process began in October and included a series of town halls in November.

The commission is currently analyzing input at public meetings and accepting district map proposals through April 15.

Once the map deadline has passed, the commission will narrow down proposed maps to three options. The commission will then hold another public meeting for a final round of community input and submit a final map to Dallas Mayor Eric Johnson sometime in May

“We have to get to a final map that a majority of the commission supports and submit it to the mayor,” Oliver said. “It’s my goal that we achieve unanimous support for the map.”

The City Council will then have 45 days to adopt the map or modify and approve a new map. If the council does not approve a map by the deadline, the commission’s version of the map will automatically be adopted.

This year’s redistricting process will also be the first since 1972 in which the city of Dallas will not require district map approval from the U.S. Department of Justice due to a 2014 ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court.

The new district boundaries will go into effect for the May 2023 City Council election.

Valerie Wigglesworth contributed to this report.