More than a year later, three nonprofit leaders from Christ’s Haven for Children in Keller, Pajama Rama in Roanoke and Community Storehouse in Fort Worth share how they persisted and lessons they learned.

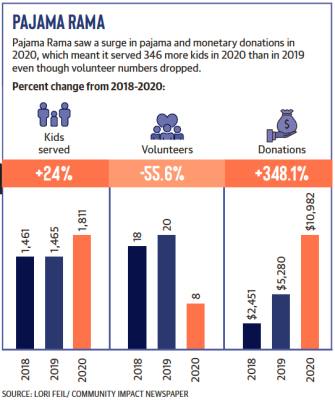

Roanoke-based Pajama Rama beats fundraising record with virtual drive

When Lori Feil’s 6-year-old daughter crashed her scooter and ended up at a children’s hospital in 2013, Feil said the “super traumatic” experience made her want to give back.

After exploring the children’s hospital’s website for items to donate, she saw in bold letters the word “pajamas.” She started with a single box in her front yard for people to donate pajamas.

In 2018, Roanoke-based Pajama Rama became a nonprofit, with Feil as its founder and chief executive officer. Slowly but surely, she said she expanded to helping other local children’s hospitals and partnered with children’s advocacy agencies to also serve kids who are disadvantaged, abused and neglected.

“We went from having one box in my front yard to having ... close to 40 all over DFW,” Feil said.

Feil said the nonprofit still had about 20 boxes spread out among the community when the pandemic started. She said she was worried the boxes would stay empty as people locked themselves inside.

But then she got creative. She put a QR code, which linked to the nonprofit’s website, on all the Pajama Rama donation boxes, and she began a virtual pajama drive to raise funds in lieu of pajamas. Feil said donations came in like crazy, and the nonprofit collected more pajamas than ever before.

Because of the code’s success, Feil kept it. Now, the nonprofit is hosting its major pajama drive until Dec. 10, with 50 donation locations throughout the DFW area.

“I think, bottom line, people want to give, and people want to help out in the community,” Feil said.

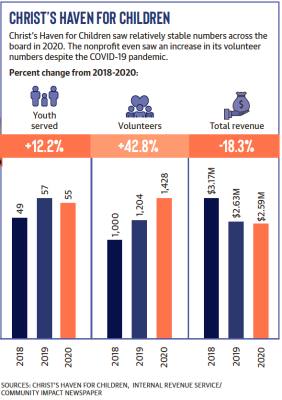

Christ’s Haven for Children expands services for those struggling amid pandemic

In 1954, Homer and Lillian Steadman bought a large Fort Worth home for disadvantaged children. The couple ended up caring for 10 children, but realized the need was greater than the space they had. In 1956, the Steadmans and a few other families purchased a farm in Keller and established Christ’s Haven for Children.

Christ’s Haven now has a 58-acre campus, including seven cottages, a life path house, a teen mom house, a chapel, a pavilion, a workshop, a barn, a swimming pool, sports courts and playgrounds. The nonprofit’s main program is its residential one, where displaced kids and teens can get family-based care rather than end up in foster care.

“Our core values are normalcy, dignity and hope for our kids,” Christ’s Haven CEO Cassie McQuitty said.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, McQuitty said the nonprofit’s resale store—which makes up about 10% of the overall budget—had to close for a while.

“We did what every other family did—we tightened our belts where we needed to [and] got really smart and strategic about how we were spending money and what we were willing to spend it on,” McQuitty said.

However, she said they were “pleasantly surprised” to see the drastic increase in in-kind donations, especially to the food pantry. And because of the massive increase in donations, the nonprofit was able to do something it always wanted to do—expand services to those outside its campus.

Now, through partnerships, Christ’s Haven is offering gap services, where local families in need of support can get weekly food boxes, counseling services and care packages.

“What we saw during this pandemic that we sometimes forget is everybody felt and saw the urgent need happening, and people responded—often sacrificially,” McQuitty said.

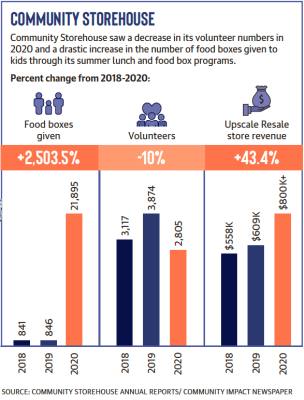

Community Storehouse stretches outside service area to benefit more students

Community Storehouse has a simple yet crucial mission: to close “the gap between opportunity and achievement for the children in our community,” the nonprofit’s website states.

“We work hand-in-hand with Keller, Carroll, Argyle and Northwest school districts to make sure every student has what they need to be successful in the classroom,” said Brandon Board, Community Storehouse director of sales.

To do so, Community Storehouse offers various resources, such as a food pantry, school break programs, snack packs, dignity closets and educational programs.

But when COVID-19-induced lockdowns began, Board said the nonprofit had “to drop all” of its volunteers, since most are older adults at higher risk of COVID-19 complications.

“It takes about 110 people a week for the operation to be successful, and I have just 24 paid staff members,” Board said. “So you can imagine, over time, that we were burning the candle at both ends.”

Community Storehouse especially began to feel the pandemic’s effects when the unemployment rate skyrocketed, Board said. The nonprofit saw a lot of new clients struggling for the first time.

Board said their nutritional center served about 45 families in 2019, and that number shot to about 250 during the “heart of the pandemic.” The need became so great that Community Storehouse loosened its demographic qualification for services. But the nonprofit also saw an increase in donations and Upscale Resale store revenue.

“[Our policy] was, ‘if you need it, come get it,’” Board said.

Since then, Community Storehouse has “slowed back down,” Board said. It is back to servicing just the four school districts to maintain stability. But the nonprofit is continuing something it started during the pandemic—emergency boxes with a four-day supply of food for four people who live outside its service area, Board said.