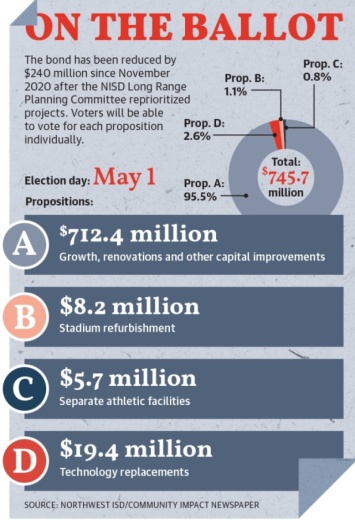

The Northwest ISD bond election on May 1 will let voters decide on four separate measures, after the previous bond election failed. In November 2020, only 28.71% to 44.08% of voters said “Yes” on the four bond propositions.

The Northwest ISD bond election on May 1 will let voters decide on four separate measures, after the previous bond election failed. In November 2020, only 28.71% to 44.08% of voters said “Yes” on the four bond propositions.“At this point, being a year behind on our schedule, it really becomes something that is going to have a major effect on our community,” NISD Assistant Superintendent for Facilities Tim McClure said.

When the Northwest ISD board of trustees called a bond election in early 2020, officials had no idea that election would be pushed from May to November by the COVID-19 pandemic, where it was forced to compete for attention with a presidential election and voters’ financial concerns. Still, growth and development in the district did not slow down in response to the pandemic, and the district needs space for new students.

“Independent school districts just don’t have the ability to turn kids away,” said Dax Gonzalez, division director of intergovernmental relations for the Texas Association of School Boards. “We want appropriate class sizes, ... and it takes money to build the buildings. Some buildings haven’t been updated in 20 years.”

Dollars and cents

The November bond election was up against several obstacles. NISD Place 7 trustee and NISD parent Jennifer Murphy said she heard from voters who were confused by the nature of school financing in Texas. Compounding the problem, COVID-19 precautions moved the election from May to November, and the voter education campaign to address that confusion had to compete with the presidential election cycle, Assistant Superintendent Tim McClure said.NISD Executive Director of Communications Lesley Weaver compared a bond to a loan that a family takes out for home renovations.

“There might be some families that can afford to [pay] ... out of pocket [for repairs],” she said. “A lot of families need to take out a loan, ... and that’s kind of what school districts do.”

“There might be some families that can afford to [pay] ... out of pocket [for repairs],” she said. “A lot of families need to take out a loan, ... and that’s kind of what school districts do.”Essentially, when Texas school districts issue bonds, they take out loans from investors to pay for targeted projects, such as building new schools or updating old facilities. Over time, the districts pay off those projects using money from the interest and sinking, or I&S, property tax rate, one of two such taxes that support schools. The other, the maintenance and operations, or M&O, tax rate, functions more like a general fund, according to Gonzalez. It pays for teacher salaries, utilities, and other daily expenses.

Regardless of whether any of the 2021 bond propositions pass, the district tax rate will remain the same at $1.3363 per $100. Although there is no proposed change to the tax rate on the May ballot, Texas state law requires that bond propositions include the phrase, “This is a property tax increase.”

Assistant Superintendent Tim McClure said that is because new developments, such as neighborhoods or retail centers, turn farmland that was exempt from property taxes for agricultural reasons into taxable property. Development makes the area more valuable as well, which increases overall property value.

“Just because they’re not raising their tax rate doesn’t mean [taxes] won’t go up because taxes are tied to value,” Gonzalez said. “You might have the same rate, but because the value goes up, you’re going to get a higher tax bill.”

Districtwide impact

The 2021 bond proposition includes items that would impact the entire district, but schools in the highest-growth parts of the district are under the most pressure.

The 2021 bond proposition includes items that would impact the entire district, but schools in the highest-growth parts of the district are under the most pressure.“We normally yield 0.5 kids per house. In the south [of the district], we’re yielding one child per house,” Executive Director of Planning Sarah Stewart said.

Adams Middle School, which serves portions of north Fort Worth, is already almost 200 students over capacity, which Principal Matrice Raven said makes it hard to uphold NISD standards.

“When we are so big and over capacity, ... we are operating under constraints that ... cause us to be creative,” she said.

For example, some classes are held in temporary, portable buildings, and to prevent lunchroom crowding, the school’s first lunch period begins at 10:30 a.m. Some students also eat outside, she said.

If the bond does pass, the district’s seventh middle school would be built in nearby Haslet, which would relieve some of the pressure on Adams.

According to Gonzalez, the school bonds issued by Texas districts to fund new learning facilities overwhelmingly passed in 2020, despite the pandemic and the economic fallout it caused.

“There’s almost a 70% pass rate for bonds. It’s really shocking all of [NISD’s] bonds failed,” he said.

When vital bond propositions do fail, Gonzalez said, it is often because of miscommunication. This time around, NISD has made clarity and communication a priority by rolling out a new website about the bond and providing social media updates.

Murphy and Weaver both said district residents have been far more engaged with the current bond and that people are asking more questions to educate themselves.

“We’ve received triple the amount of questions we received in the fall. To me, that’s a good thing,” Weaver said.

Though officials are unsure as to whether increased engagement will mean a more favorable outcome for the bond in May, they said they remain optimistic.

“It’s a million-dollar question—maybe a trillion-dollar question,” McClure said. “I think there’s hope.”