Local and state officials are examining strategies and pursuing legislative measures to combat the rising suicide rates and find what plays into the increase throughout the state of Texas—and specifically in Montgomery County.

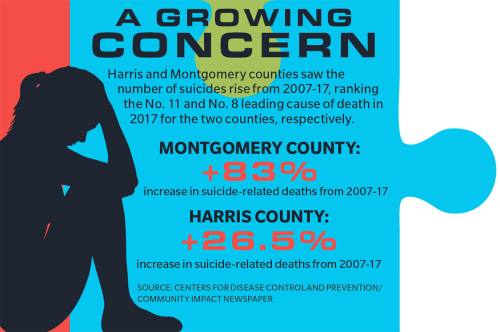

Suicide-related deaths in Montgomery County increased almost 83 percent from 47 deaths in 2007 to 86 in 2017, according to data released in December from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Harris County saw a 26.5 percent increase in suicide-related deaths during that time from 388 to 489 deaths.

As the number of deaths has increased, intentional self-harm—or suicide—moved from the No. 9 leading cause of death in Montgomery County in 2007 to the No. 8 leading cause of death in 2017, according to CDC data.

Across the decade, the number of suicides also increased among youth statewide and nationwide, according to CDC data.

While several resources in Harris and Montgomery counties exist to address mental health, the number of resources is inadequate to serve the population, said Sherry Burkhard, director of education for

Mosaics of Mercy, a Magnolia-based nonprofit connecting clients to mental health and addiction recovery resources across the U.S.

“Mental health problems are absolutely on the rise, especially anxiety and depression,” Burkhard said. “The whole reason we opened here is to serve this portion of the community that does not have the same access

to services.”

Youth suicide rates increase

CDC data shows suicide was the No. 2 leading cause of death in both the state and nation for ages 10-34 in 2017. The year also marked the first time suicide was the second leading cause of death for ages 10 to 14 in Texas.

In Montgomery County, there were three confirmed suicides by residents younger than 17 and 15 suicides by residents younger than 25 in 2018, according to the Montgomery County Sheriff’s Office. Unofficial tallies by the Harris County Institute of Forensic Sciences indicate 21 suicides by residents younger than 17 and 89 cases by residents younger than 25 in 2018.

Burkhard said a combination of factors is contributing to the nationwide trend of increasing youth suicides and mental health issues.

“There’s just a huge amount of pressure [youth] are feeling, whether it comes from their parents, from themselves, whatever it is,” she said. “All of that combined makes them feel a tremendous burden that their brains can’t handle because they aren’t fully developed.”

Middle- and high-school age children cannot escape bullying the way previous generations could because of the existence of social media, which may contribute to increased stress and trauma, said Michael Webb, Tomball ISD assistant superintendent for student support.

“One person can comment something negative on someone’s [social media] post, and the entire school—or the world—can see it and have the ability to comment back,” he said. “It’s so easy for kids to believe negativity if it’s coming from so many people.”

Adriana Gutierrez, director of counseling services at Montgomery County Youth Services, said the nonprofit has seen a spike in suicidal ideation—the talk or thoughts of suicide, rather than the act itself—among clients as well as a spike in trauma-related experiences.

She said population growth may contribute to the rise in suicides and mental health issues as well. Montgomery and Harris counties saw the populations increase 36.1 percent and 17.4 percent, respectively, from 2007-17.

“I’ve lived in this area almost 20 years now, and there’s been a huge migration toward [Montgomery County],” she said. “With that comes more people and more exposure to different life experiences.”

Evan Roberson, executive director of Tri-County Behavioral Healthcare—which offers comprehensive services for those with mental illness as well as intellectual and developmental disabilities in Liberty, Walker and Montgomery counties—said the organization’s crisis services have seen patient numbers increase over the past three years, with 2018 showing a 20 percent increase. He said the number of adults and children seeking crisis services is up 10 percent and 7.5 percent as of March, respectively, over last year.

“What we see in kids is a significant traumatic event in their lives—and many significant traumatic events in some cases—that they haven’t learned how to cope with,” Roberson said. “They just aren’t doing well in their day-to-day lives, so I just think suicide becomes an option for them.”

Local efforts

While there are several mental health facilities in Montgomery County, including Montgomery County Youth Services, Tri-County Behavioral Healthcare and Woodland Springs, Magnolia is not home to many services, Burkhard said.

“Since there aren’t as many resources in this area, that’s going to affect the residents’ ability to get somewhere, especially during school or work hours,” she said.

Lt. Brian Luly, who is part of the mental health division and Crisis Intervention Team for Precinct 1 in Montgomery County, said his office averages about six calls per day of someone in crisis. This includes those having a psychotic episode, threatening self-harm or attempting suicide, he said.

“Sometimes people just feel lost or embarrassed [about having a mental illness] because of the stigma around mental health. It’s a disease, just like cancer,” Luly said. “We’ve got to stop that stigma and start talking about mental health more.”

Webb said TISD launched a three-tiered mental health initiative last fall funded by a grant from the Tomball Regional Health Foundation, which includes in-person mental health training for all teachers and administrators with the Center for School Behavioral Health and implementing substance abuse assessments and interventions from Teen and Family Services.

Meanwhile, Magnolia ISD has two representatives from Tri-County housed within the district to work with parents and students on mental and behavioral health, MISD Communications Director Denise Meyers said in an email.

MISD also partners with Montgomery County Youth Services to provide counseling, and the district launched a parent engagement program in December, which has included sessions on social media and mental health as well as an upcoming April session on anxiety and depression, Meyers said.

Montgomery County is slowly providing more mental health resources and facilities, but the number of resources is still limited, which may contribute to the growing number of suicides, Luly said.

“I’m sure there’s more people that need the help than we have beds for, so it is a growing issue. [Precinct 1 has] actually sent letters to the senators of our county to help address that on a state level,” he said.

‘A word people don’t say’

Across the state, legislators are weighing in on the issue. A group of state senators, including Brandon Creighton, R-The Woodlands, and Paul Bettencourt, R-Houston, authored Senate Bill 10 on Feb. 5.

SB 10 would establish the Texas Mental Health Care Consortium, a collaboration of health-related institutions to improve early identification and access to mental health services, address psychiatry workforce issues, promote and coordinate mental health research, and strengthen judicial training on juvenile mental health.

It would also establish Texas Child Access Through Telemedicine to connect at-risk youth with behavioral health assessments and intervention programs through telemedicine and other cost-effective, evidence-based programs, according to the bill.

The Senate budget proposal allocates $100 million in new funding for SB 10 in addition to SB 1, which allocates $7.5 billion across 21 state agencies to address mental health.

As of press time March 26, SB 10 was approved by the Senate but awaits assignment to a House committee.

“After the hearings throughout the summer, the Committee [on School Violence and Safety] understood the urgency of identifying at-risk youth and getting them the help they need to fully rehabilitate,” Creighton said in a Feb. 13 press release. “It’s one of the most important issues we have to address this session and I am committed to prioritize[ing] mental health initiatives.”

Roberson said he believes there has been significant growth in the demand for mental health care because people are more willing to seek care than they used to be. He said it is important for the community to discuss mental health.

“One of the myths of suicide is that if we don’t talk about it, people won’t do it. That’s just not true,” he said. “Having frank conversations with your kids, with your friends and with your family is important. [Suicide] is a word people don’t say, but we need to be saying it.”

Additional reporting by Andrew Christman