But while congestion has been lighter in recent months as residents work from home during the coronavirus pandemic, Foster said he knows as the pandemic recedes, traffic will return and continue to get worse each year.

“I can go stand at a stoplight on Menchaca Road on a weekday morning, and there will be two to three dozen cars stacked up waiting to go north,” he said. “When you look at the cars, maybe 90% of the time you’ve got only one person in each one of those cars.”

The city of Austin and Capital Metro will ask Austin voters in November to fund a plan that would connect Austin neighborhoods to downtown through public transportation in an effort to reduce the number of cars on the road and provide transit access to residents who do not own vehicles.

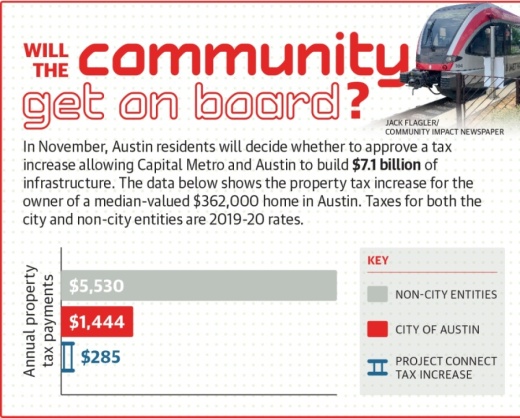

Project Connect, a $7.1 billion investment with about $3.85 billion coming from local property tax funds, would include two light-rail lines, an additional commuter rail line and a downtown underground train station. Capital Metro’s board initially approved a $10 billion plan, which could still be built if additional funding sources become available in future years.

District 5 Austin City Council Member Ann Kitchen said Project Connect outlines a communitywide investment that could greatly aid those in South Austin.

“It’s bus improvements; it’s rail; it’s park and rides; it’s neighborhood circulators; it’s metro bikes; so it’s really a whole transportation package, and South Austin gets a piece of all of that,” she said.

South Austin investments

One new light-rail line, the Orange Line, is the largest investment to touch South Austin within Project Connect. Voters will decide Nov. 3 whether to fund a $2.3 billion line from the North Lamar Transit Center to a future station at the corner of South Congress Avenue and Stassney Lane. A second $1.7 billion phase, which is not part of the funding decision in front of voters, could extend the line north to Tech Ridge and south to Slaughter Lane.

Kitchen said Project Connect would bring changes to bus service and parking options as well.

Specifically, MetroRapid bus service—which offers rides every 10 minutes on dedicated lanes—would be expanded along Menchaca south to Slaughter. A MetroRapid line would also be introduced to South Pleasant Valley Road in Southeast Austin, a move that Kitchen said would help serve one of the lower-income areas in the city.

The city is also exploring 15 circulators—a neighborhood transit option that would connect residents with main metro bus routes—eight of which are south of the Colorado River.

“You can’t run a bus through the middle of every neighborhood, so the circulators are ready to help people get to the bus system,” Kitchen said.

Austin voters will decide this fall whether to increase their property taxes to fund Project Connect’s $7.1 billion price tag. The increase is 8.75 cents per $100 of valuation. For a home valued at $250,000, the annual property tax bill would increase by $197, while a bill would increase by $394 for a home valued at $500,000.

Peck Young is a longtime political strategist and the executive director of Voices of Austin, a group calling for local government to take a new path.

Young said the cost of light rail to Austin property taxpayers is not worth the return.

“I personally think, and most of the people I’m working with think, that there is no sound reason Austin should get stuck with an expensive subway here at the beginning of the 21st century when most cities are having issues with maintenance and operating costs,” Young said.

Traffic problems multiplying

Projections from the Capital Area Council of Governments, a collaboration of local governments in the 10-county Central Texas region, show the area’s population is expected to balloon from about 2.4 million to roughly 4.1 million by 2040.

Even if work behaviors change after the coronavirus pandemic, Capital Metro President and CEO Randy Clarke said traffic will continue growing significantly worse as the population grows if Austin does not take action.

Austin resident Brandon Miller runs a firm that specializes in consulting and marketing for residential home developers and focuses on neighborhoods along South Congress Avenue, where the proposed Orange Line would be built.

“Austin needs to get to the point where not everybody needs a car,” Miller said.

The benefits, Miller said, would likely extend to housing prices in new developments. If Austin built a light-rail system, the city would be in a better position to lift its current requirement that necessitates at least two parking spaces for every single-family home, duplex unit or townhome. That, Miller said, would make housing cheaper to build. He said each parking spot costs developers about $40,000 to build.

“Developers are losing money on parking. Eventually that cost has no choice but to be baked into the price of the home,” he said.

However, the price of existing housing around the light-rail lines would likely increase because of the new options to get around the city. That is a benefit for property owners if they want to resell their house, but the resulting increase in taxes also has the potential to overburden homeowners.

A 2014 study from the University of Minnesota found that when an 11-mile light-rail line was built between St. Paul and Minneapolis, home values increased by $13.70 per square foot between the announcement of the federal grant in 2011 and operations starting in 2014.

‘The opposite playbook’

If Project Connect were built in an equitable way, Carmen Llanes Pulido—executive director of local health access nonprofit Go Austin/Vamos Austin— said she has no doubt it would have a “phenomenally positive impact.” But she said the communities GAVA serves have little faith in the city to execute its promises because of Austin’s history.

“Displacement is imminent with a light-rail system. You better have all your anti-displacement and affordable housing initiatives penciled in from the beginning,” she said.

Local leaders recognize that inflating home values along the transit lines could deepen city divides.

Baked into Project Connect is a $300 million investment intended to make sure the new public transportation lines are built to serve the people in the neighborhoods they will traverse, not drive them further out to Austin’s periphery.

District 1 City Council Member Natasha Harper-Madison—who has spent her entire life in Austin—said the opportunity exists now to build a system that does not repeat the destructive past of city transportation projects but exists as something residents can take pride in.

“I see Project Connect as a chance to run the opposite playbook of what we did in the past,” Harper-Madison said.

The exact uses of the $300 million have not been spelled out specifically, but options include buying land to build affordable housing, home repair, rental subsidies and financial assistance for home ownership.

“That’s all designed to help people with housing opportunities because we recognize housing and transportation go hand in hand,” Kitchen said.