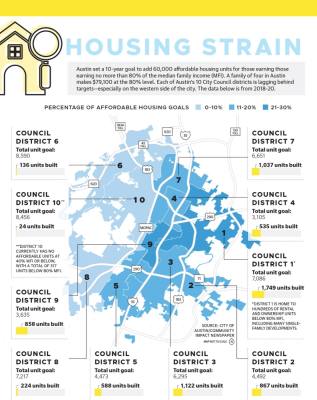

However, by the end of 2020, the city had reached 12% of its 10-year goal to ensure tens of thousands of new homes and rental units would be available to those earning less than the area’s median income, according to a city report released in September.

City staff, housing advocates and others have pointed to the city land development code, last revised in the early 1980s, and the time and cost for any new development these days as key reasons for the lagging progress.

“Status quo is a failure for the city of Austin,” said Greg Anderson, an Austin Habitat for Humanity representative and University of Texas lecturer. “It will only get worse moving forward.”

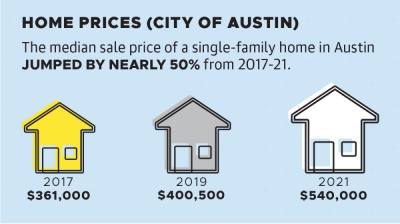

Austin’s population shot up more than 21% in the past decade, from 790,390 to 961,855. That further strained the housing market and forced many to reevaluate their options. A growing gap between prices for homes and rental properties and the slower growth of residents’ paychecks means many are seeing options for stable housing slip away. New housing goals

Jamey May, Austin’s acting housing and community development officer, said the Strategic Housing Blueprint, passed in 2017, outlines a path forward.“We need housing for a wide variety of income levels,” May said. “The other [guideline] is we need them everywhere in all 10 council districts.”

So far, Austin is off track on both of those fronts.

From 2018-20, the city added 7,140 units, less than 12% of its overall goal for 60,000 new affordable units by 2028, according to the blueprint. The plan defines those units as affordable to those earning 80% or less of the median family income.

Under the city’s plan, these homes can be single-family or apartments, available for rent or purchase. Some of the units will be built through city projects, such as the redevelopment of the St. John city-owned lot into multifamily housing. Others will come from developers adding affordable components to their plans, per city regulations.

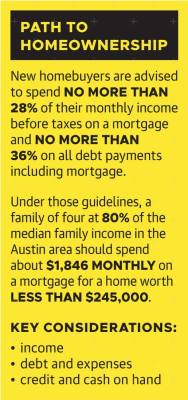

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development views housing costing less than one-third of a person’s income as affordable. Austin also measures affordability based on income and family size. Households are considered to be in a low income housing bracket when earning 80% or below the area’s median family income.

In Austin, the median family income is $98,900 for a family of four. Nearly half of Austin’s population is considered to be low income by this housing metric, according to city data.

While the city fell behind on all of its goals in the first three years, it struggled the most adding units it hoped would serve “extremely low-income” individuals, those making 30% or below the median family income. Austin achieved about 1% of its goal in this category, according to the report.

Austin’s progress for more affordable housing remains slower on the city’s west side, HousingWorks research manager Woody Rogers said.

“We need to make sure that we’re identifying opportunities in all parts of Austin ... because either there’s a lack of affordable housing in these areas or because they’re areas of high opportunity that we want to make sure that people with lower incomes are able to access as well,” he said.

While no City Council district is on track to hit its goal, the worst-performing districts are 6, 8 and 10, mainly west of MoPac. Those districts saw 384 new affordable units added through 2020 out of a combined goal of 24,263, according to the report.

District 10 Council Member Alison Alter said her 2017 vote for the blueprint plan came with an understanding that the 10-year, 8,456-unit goal for her area was “unrealistic” from the start, given a local market that “will not provide affordable housing on its own.”

She said the district would need considerable investment to meet the targets.

Three Central and East Austin districts are faring better, adding nearly 3,500 units in total out of more than 15,000 targeted, according to the blueprint.

Policy barriers, forging ahead

The land code, which sets development requirements such as height and density, currently restricts more affordable options, according to some housing advocates.

In 2012, city officials began looking at a policy rewrite, a plan known as CodeNEXT. After CodeNEXT was shot down by city leaders, a new proposal became the subject of a 2019 lawsuit that remains tied up in the courts.

The issue of rewriting the code has divided some residents. Some are concerned over landowners’ rights to have a say in local development and existing neighborhood qualities. Others have questioned whether a large-scale code rewrite is necessary, given the total number of houses, condos and apartments continuing to rise across town.

Another segment has suggested limiting single-family zoning and focusing on denser options.

Officials have chipped away at parts of the code over the years with policies such as targeted bonus programs. Those give developers permissions such as additional height or building area in exchange for affordable housing or related fees.

The city and observers have also acknowledged that Austin’s current permitting process is hindering some development.

“We’ve actually seen that over the years, our fees and our development permitting times have just gone up,” said Awais Azhar, a member of the Planning Commission. “For particularly affordable housing providers and people who are working to essentially save every bit of money ... the challenge then becomes that we’re adding extra costs and burdens.”

Despite slow-changing policy and disappointing headway, there is still time to turn the situation around, HousingWorks Executive Director Nora Linares-Moeller said. She said whatever council members do now can affect the city’s future progress.

“We try to remind people of how difficult it is to put affordable units on the ground ... you can’t stop,” she said.

Some of the city’s strategies include continuing to invest the $40 million of remaining 2018 housing bond dollars and pursuing vacant land for accessible housing. May is also hopeful the federal government will change how it assists with housing.

Where this leaves Austinites

Whether backed by the city or nonprofits and private developers, new affordable projects are breaking ground each year.

Private developments such as The Quincy and Aura on Lamar, two apartment complexes in the MLK Station area, and Pathways at Goodrich Place developed by the city housing authority, have recently added affordable units. For residents in need of less costly spaces, the city’s focus on affordability can prove essential to keeping them in town.

Maryse Saffle, who owns a home in the Mueller district, said she feels like she “won the lottery.”

“I think my experience is fairly rare, and I am conscious of that and grateful every day,” Saffle said.

But while the city continues to grow, housing prices are not easing up, a fact analysts said will further drive the need for more of this type of housing.

“Whether you realize it or not, it affects you,” Linares-Moeller said. “We’re talking about neighborhood workers, people that should be able to live close to their jobs just like you. If you start to look at who needs housing that’s affordable, you will be surprised at how people who are members of your family and people that work in your local stores are the people that are most affected.”

Azhar said the issue should matter to all residents, regardless of income.

“If you’re a taxpayer, if you’re someone who wants to see a city function in the best way, there’s things we should be wanting,” Azhar said. “For example, having those housing opportunities for folks is critical for economic growth.”

Despite earning what he considers a “decent” income, former Austin resident John Halverson said rising rental prices over the years forced him and his wife to frequently move around the city, trying to find a place they could afford. They ultimately moved back to Montana where he said they hope to get a financial foothold and start a family.

“We have somewhere we can afford to live that still gives us a path to the middle class,” he said. “I know most aren’t as lucky.”