On March 31, three employees reported to the facility’s executive director, John Redford, that they may have been exposed to COVID-19 after they had family members test positive. While Redford said Village on the Park reacted swiftly and appropriately, sending the employees to be tested and assessing any points of contact they have had, public reaction was strong when word leaked the employees had the virus.

“There was a general hysteria,” Redford told Community Impact Newspaper. “Those days were hard. I act like it was a year ago, but we’ve learned so much so fast.”

Redford fielded phone calls “for a week straight” from concerned family members of residents and staff. Ultimately, only one resident out of 120 decided to leave Village on the Park due to coronavirus fears, and they returned two weeks later. No other staff or residents have tested positive for COVID-19 at the facility since the initial three staff cases as of press time.

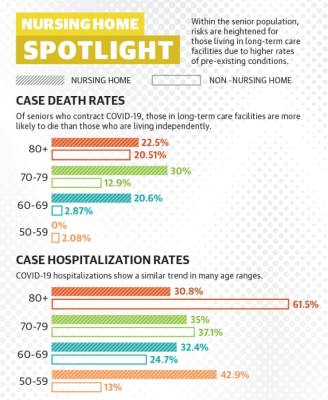

However, Village on the Park’s experience has not been the outcome for some other South Austin senior care facilities, where COVID-19 has often spread rapidly and caused higher rates of hospitalization and death compared to the general population.

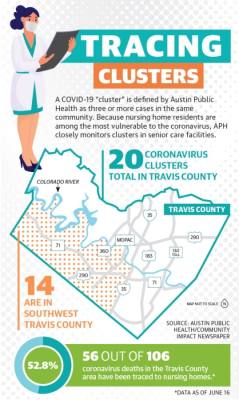

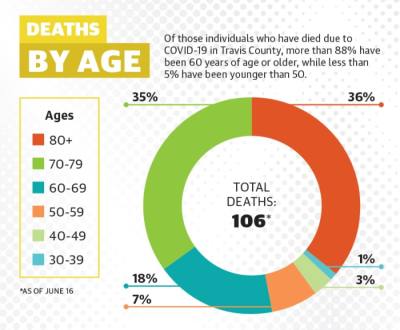

According to Mark Escott, Austin-Travis County interim health authority, 20%-25% of nursing home residents who contract COVID-19 locally die. In Travis County, 56 of the 106 coronavirus-related deaths confirmed as of June 15 were from cases in senior care facilities, and around 9% of all confirmed coronavirus cases have been senior care residents and staff. Older adults are already among those with the highest risks associated with the virus, with people age 70 and up accounting for 70% of all coronavirus-related deaths in Travis County.

In Southwest Austin, these effects have been apparent: 14 of Travis County’s 20 coronavirus clusters in senior care facilities are located south of the Colorado River and west of I-35 as of June 15, according to Austin Public Health.

Facilities ramp up restrictions

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has created tiered guidance for senior care facilities to follow during the pandemic depending on their active cases. Tiers give recommendations to those facilities trying to stay coronavirus-free—such as the Auberge at Onion Creek, a memory care center that has proudly touted its virus-free status—and to facilities already battling outbreaks—such as West Oaks Nursing and Rehabilitation on West Slaughter Lane, which had 82 confirmed cases and 22 coronavirus-related deaths according to the Center for Medicaid and Medicare as of May 31.

In accordance with CDC guidelines, many facilities have restricted visitor access, cut communal activities for residents and required face mask use among staff. Staff temperatures are tested upon entry, and resident temperatures and potential symptoms are regularly monitored as well.

With these restrictions in place, the most likely source of coronavirus infection is a staff member, since facility administrators like Redford have no control over the comings and goings of staff outside of work. This possibility, Redford said, is “what worries [him] at night.”

“We preach. We tell [staff] that if we get COVID-19, it’s most likely going to be from an employee,” he said.

Caregivers who work with seniors—often low-wage earners, according to multiple employers Community Impact Newspaper spoke to for this piece—have also often been required to choose between the multiple jobs they held prior to the pandemic.

This measure minimizes the risk that they will carry COVID-19 from one medical facility to another, according to Margaret DeVinney, director of education for Halcyon Home, a home health provider that staffs the wellness centers at a number of Southwest Austin senior care communities.

“Under COVID precautions, every community in town is asking ‘where else are you working?’” DeVinney said. “We can’t have caregivers spreading germs.”

Residents feel pressure

While these restrictions aim to keep residents safer, they frequently come at the cost of isolation. Some seniors have gone months without in-person visits from loved ones and without venturing beyond the care communities where they live.

“We closed down visits three months ago. Many of our residents have not touched, hugged, seen, been in front of their family members for that long,” Redford said.

Those who have seen visitors have mostly done so through one or more barriers—an iPad screen, a window, a fiberglass shield, a mask.

Claude van Lingen, a resident at Elmcroft Senior Living on Menchaca Road, celebrated his 89th birthday in March with his daughter, Rietta McKnight, from opposite sides of his bedroom window. She sang him “Happy Birthday” through the glass.

“It would have been nice to take him out somewhere, but we just had to comply with what needed to be done to keep him safe,” McKnight said.Van Lingen, an award-winning artist, has used the extra time to keep up with his art and work on other projects.Many of van Lingen’s peers, however, have been hit harder by social and physical stagnancy.

“We have noticed decline, both cognitively and physically, in our beautiful friends of our greatest generation,” DeVinney said.

For seniors with pre-existing dementia and cognitive impairment, lack of stimulation and contact can be especially debilitating, multiple senior care professionals said. Some struggle to understand the situation of the outside world, and wonder why protocol has changed so much and they cannot see loved ones face-to-face.

Anna McMaster, owner of the South Austin location of CarePatrol, which helps clients find an ideal senior care community, has dealt with these challenges on a personal level with her father-in-law, who has vascular dementia.

“We don’t even call him much anymore because it actually confuses him more,” McMaster said.

As the pandemic has progressed, seniors and staff have adapted and found ways to cut the sense of isolation. Some residents have moved chairs outside their doors to chat with friends across the hall while masked or to participate in hallway bingo games, Redford said. Seeing this progress, he said, has been “a joy.”

Feeling the way forward

Village at the Park has cautiously begun to accept new residents again, testing new intakes and requiring them to quarantine upon arrival, according to Redford. He said his confidence in the safety in his own facility, as well as his impression of the industry’s education on coronavirus prevention at large, is much heightened since his three employees tested positive in March.

“I’ve been doing this for over 20 years, and I’ve probably learned more in the past three months than in all those years,” he said.

Some seniors and their families opted to leave senior care communities when concerns over the coronavirus emerged, hoping to reduce the risk of infection. Many of those individuals are now headed back to their communities, and some who were holding off on checking family members into a facility are ready to take the plunge, according to McMaster.

“March and April were really quiet for me, but by the time May rolled around, I was getting calls from people who couldn’t live on their own safely anymore,” McMaster said.

Some notes of optimism arose in Travis County following the late May completion of Gov. Greg Abbott’s direction to conduct universal testing at all of Texas’ skilled nursing facilities, the subset of senior care facilities where the most clusters have formed due to how many patients have underlying conditions. Two asymptomatic residents tested positive. Following those results, Escott expressed hope that vulnerable residents, including older adults in nursing homes, can be protected if appropriate measures continue to be taken by the public at large.

“If we can effectively cocoon those individuals by rethinking how we protect nursing homes and other areas where elders congregate, if we can really take seriously protecting our front-line workers, protecting our communities of color, ensuring they have adequate access to primary care and to testing and isolation, then the economy can open up,” Escott said.

However, renewed concerns about community spread have formed since Escott made those comments June 2 with an increase in coronavirus cases in Travis County. On June 9, Escott also said the cost of continued testing in senior care facilities was becoming prohibitive, and innovative measures, such as batch testing of 20 or more people at a time, with individual tests forthcoming in the case of a positive batch, may be necessary.

If community spread continues to increase as Escott predicts, the threat to seniors increases along with it. Nursing home residents will likely have to wait even longer to see their loved ones in person—including those in hospice, whose days are numbered. Nursing home directors say that for those residents, the course of the virus, and choices of the public outside the walls of their communities, could determine the way they spend the time they have left.