After a busy 2019 in which Austin’s homelessness challenges and the ongoing effort by the community to rewrite its land-development rules dominated headlines, 2020 is set to be highlighted by what many see as a pivotal election cycle.

Austin Mayor Steve Adler said residents on Nov. 3 will likely be casting a “generational vote,” as the community decides whether to support a multibillion-dollar bond proposal to finance plans for more robust high-capacity transit. Plans released in January laid out the potential options that could land on the November ballot, which range from a $3.2 billion rapid bus system to a $10.3 billion urban rail system with a 1.6-mile downtown subway tunnel.

Austin and San Antonio are the only cities among the country’s 11 largest to lack a high-capacity transit system, according to analyses by Community Impact Newspaper. A high-capacity transit system is one that can move people throughout the city in greater numbers and frequency than a conventional bus system. These transit options often operate outside of traffic, such as a bus with dedicated lanes or a light-rail system.

“Mobility and congestion have kind of been the preeminent issues among people since before I ran for mayor [in 2014],” Adler told Community Impact Newspaper. “When you talk to people, it’s one of the first things people say they want to be fixed.”

Transit and city officials have been working on the 2020 proposal for three years and said they are learning from the mistakes made in the failed $600 million urban rail bond referendum in 2014. Although officials are confident voters will approve the plan and financing, some challenges lie ahead.

Also on the local November ballot, voters will decide on five Austin City Council seats, four Austin ISD board of trustees seats and two seats on the Travis County Commissioners Court.

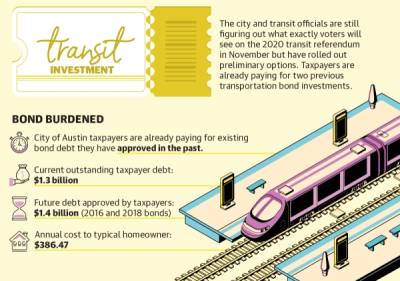

Since 2016, Austin voters have passed roughly $1.65 billion in city bonds with accompanying property tax rate increases. Some neighborhood representatives have cited tax fatigue as a concern about future bonds, but the real issue in 2020, they said, is confidence in city leadership—a sentiment exemplified by active petitions circling the citizenry aimed at recalling the mayor and the five City Council members whose terms do not expire until 2022.

Mobilizing Austin around transit

The Austin metro has been the nation’s fastest-growing major metro for eight consecutive years, according to Austin demographer Ryan Robinson. That growth has continued to exacerbate transportation and traffic congestion grievances among Austinites. City officials, advocates and neighborhood representatives said the failure of 2014’s $600 million urban rail bond proposition was not for lack of want. Rather, they said, it was just a bad plan.

“It seemed to happen very quickly, and the proposal didn’t really seem to be thought out,” Adler said. “There were so many unanswered questions. This time, the plan has gone through a three-year process to get to where we are now.”

Since 2014, Austinites have remained mostly united in their resentment toward traffic congestion. Between 2015 and 2018, 67% of the 8,433 residents surveyed by the city said they were dissatisfied with traffic flow on major streets. Between 2016 and 2018, 86% of the 6,417 residents surveyed by the city said they were dissatisfied with traffic flow on the city’s major highways.

Randy Clarke, president and CEO of Capital Metro, the region’s transit agency, said the need for transit solutions is “beyond obvious” and 2020 is the time for “big, bold change in how things move in the city.”

“I feel very confident that this is going to be the year that Austin and the region advances a significant transit program,” Clarke told Community Impact Newspaper. He said the city and Capital Metro are “much further ahead” than the city was prior to 2014’s failure.

The various proposals and associated costs for the transit overhaul were laid out at a Jan. 14 meeting; however, the plan still needs ironing out before voters hit the polls in November. In March, Capital Metro officials will recommend which plan to pursue, and in May, City Council will decide what exactly voters will see on the ballot—namely, how much debt the plan will ask taxpayers to take on and whether the debt will finance a bus or rail system.

Austin ISD explores future bond

Austin ISD discussed a future bond of its own during its School Changes process last fall.

When discussing a draft of the district’s 2019 Facility Master Plan in August, AISD Operations Officer Matias Segura said the district had considered 2022 as a target date for a bond.

However, CFO Nicole Conley said at a School Changes workshop in October that a 2020 bond would “likely be needed” to renovate schools designated to receive new students from schools the trustees chose to shutter. At that time, 12 school closures were being considered; however, trustees moved forward with only four, reducing the need for an immediate bond. The district has not discussed a bond timeline since.

On Feb. 5, Austin ISD told Community Impact Newspaper that there is not a bond currently in development, and not a bond planned for 2020 .

Trust and fatigue

Austin voters overwhelmingly approved a $720 million mobility bond in 2016. In 2017, residents approved a $1.05 billion Austin ISD bond and a $301 million Travis County bond. In 2018, they said yes to a $925 million municipal bond for myriad public projects. With each approval, voters agreed to additional property tax rate increases, while, under the pressure of a hot real estate market, their property values and property tax bills continue to rise, exacerbating affordability challenges within the city.

Austin Neighborhoods Council President Justin Irving said tax fatigue has come up as a concern among ANC members; however, of greater concern is trust in leadership.

Fallout from the city’s new homelessness policies and a push to finalize a controversial rewrite of the city’s land-use rules inspired political action committee Our Town Austin to start a petition to recall the mayor and the five council members elected or re-elected in 2018. Irving said most of ANC’s membership have signed the petition. Sharon Blythe, treasurer for Our Town Austin, said she is confident the petitions will get the signatures needed by the March deadline to force a recall election in November.

Irving said ANC would “absolutely not” support an AISD bond. As for transit, Irving said ANC is generally split on the issue, but wants to see the city work to engage and inform residents about the proposals.

“There is so much potential for this town to do things better, especially on transit, that you could articulate a good plan to the citizenry and even people who are skeptical and mistrustful of the city pass it,” Irving said. “But if you try to cram things down people’s throats, I don’t see how anyone is going to be super excited about that.”

Kevin McLaughlin, a representative of urbanist advocacy group AURA, said bond and tax fatigue are less of a concern. Bond referendums tend to pass, he said, if they are attached to good plans. Although he said 2020 feels ripe for a bond, the city cannot afford to make assumptions.

“If [the city] can make the case that the bond is worth it, people will be willing to spend the money to make Austin better,” McLaughlin said.

As for confidence in city leadership, Adler said trust has to be “continually earned” but pointed to his successful 2018 mayoral re-election campaign and the overwhelming support for that year’s $925 million bond as indicative of public confidence in what City Council is doing.

“You have to take costs very seriously, but I believe this is a community that will pay for things if they believe they are of value and will improve their quality of life,” Adler said. “I think people will recognize that this is a once-in-a-generation decision. I hope and think that the public is ready for this.