The move was a legal maneuver to buy time, but the city has yet to shore up any concrete plans to address the growth.

On Feb. 15, the moratorium, originally enacted in

November, was extended for 90 days. Since its inception, 33 projects comprising dozens of homes have received waivers or exemptions to the moratorium.

“The rate of growth has far exceeded our infrastructure in transportation and wastewater,” said Planning and Zoning Commission Chair Mim James.

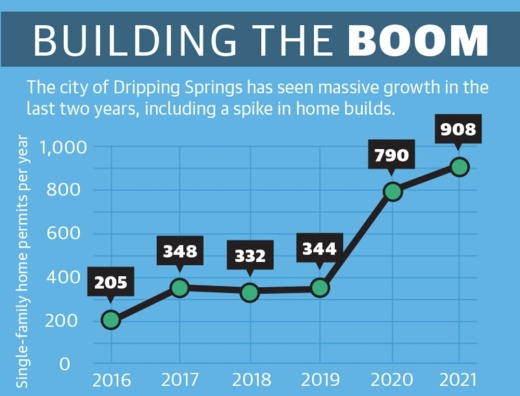

In 2020, there were 5,633 housing units in 78620, the ZIP code that covers most of Dripping Springs and its ETJ, and some additional territory.

Now, more than 4,000 new homes are in some phase of development throughout Dripping Springs, according to James.

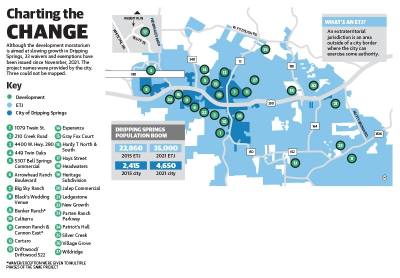

Over the last decade, Dripping Springs’ population within city limits grew by 160% to 4,650, according to census data from 2010 and 2020. The city’s extraterritorial jurisdiction, or ETJ, has close to 35,000 people residing in it, according to the city.

The ETJ is territory outside of city boundaries that the city has some control over. The area is affected by the moratorium.

“The rate of exponential growth we see in the Dripping Springs community is a very, very demanding and complex issue,” James said. “Managing that is extremely challenging. It requires resources, money, people and creative thinking. And it takes a lot of time.”

Wastewater woes

The Dripping Springs wastewater facility has the potential to treat 500,000 gallons of wastewater; however, the city can only dispose of 187,000 gallons per day through irrigation fields, Director of Public Works Aaron Reed said.

Wastewater treatment is unrelated to drinking water.

By the end of 2021, the city was using an average of 170,000 gallons of that capacity each day, according to city data.

In 2019, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality granted the city a disposal permit to discharge treated wastewater—including releasing it into Onion Creek—but that permit is currently tied up in a lawsuit filed by Save Our Springs, an environmental protection organization.

The city does not plan to discharge it into waterways if the permit is approved, Dripping Springs Communication Manager Lisa Sullivan said. Instead, it has agreements with developers to reuse the water for irrigation.

The Caliterra subdivision uses reclaimed water from the city to irrigate and is building fields to add 62,000 gallons of discharge capacity per day, according to the city.

“Our vision for Caliterra has always been that this development will respect, embrace and interact with the land and enhance the ecosystem of the Hill Country,” said Greg Rich, president of Allegiant Realty Partners, the developer for Caliterra, in a statement. “Dripping Springs is growing, and we are passionate about helping steer that growth responsibly while preserving the land and the wildlife.”

Nearby, the city of Austin discharges some of its treated water back into the Lower Colorado River once it meets state and federal quality standards.

About 60% of the water is further treated and used as “reclaimed water”—clear, odorless and not harmful to humans if they come in contact with it—which is used to irrigate properties, according to the city of Austin.

For now, Dripping Springs is not approving any new projects to receive wastewater services. Projects can receive a waiver if they were already promised the capacity or an exemption if they use a septic system.

Short of the disposal permit receiving court approval, the city is exploring other options for wastewater, Sullivan said.

Pausing the frenzy

The second reason cited in the moratorium is the need to update the city’s comprehensive plan and zoning ordinance.

Officials say the comprehensive plan and zoning ordinance—created with input from Dripping Springs residents—will delineate between areas ideal for commercial and residential development. This guiding document will help the planning and zoning commission and City Council make decisions and negotiate when development proposals come before them.

“The growth has just been outrageous and phenomenal. We love it, but we hate it,” Mayor Bill Foulds said.

Roads are so packed that businesses are forced to delay their first appointments until after the morning rush hour, and the city lacks other resources such as a police department and public transportation, Foulds said.

A few council members have expressed skepticism about how influential the moratorium will be in buying the city time to develop the plan. Council Member Geoffrey Tahuahua abstained from the February vote to extend the moratorium after stating he was unsure if continuing the land-use portion—essentially, continuing to cite the need for the updated comprehensive plan—was effective. Council Memeber Sherrie Parks voted against the extension.Mayor Pro Tem Taline Manassian has expressed concern about how the moratorium is being implemented as many projects have received waivers and exemptions.

The moratorium can only last for 180 days under the land-use provision, according to the city, meaning that clause will expire mid-summer. The city’s comprehensive plan is not expected to be finished until December.Foulds and city staff said they hope to have a better idea of what the plan will look like by the time the moratorium is lifted and begin applying its principles even if it is not officially approved by then.

The moratorium over wastewater concerns can be extended indefinitely, according to the city. Currently, it is scheduled to expire in May.

Suburban sprawl

Hays County is the fastest-growing area in the U.S., according to 2020 census data. The county grew by 83,960 residents in the decade to 241,067 in 2020.

Most Central Texas cities are seeing similar growth.

Bastrop, a city of just under 10,000 people in Bastrop County, enacted a moratorium in 2018 when development posed a flooding risk. In Taylor, a city of about 17,000 in Williamson County, officials were preparing for growth even before Samsung selected the area for a $17 billion new facility in 2021.

“We know the population is going to boom, so we are preparing for it,” Communications Officer Stacey Osborne said. “The growth is inevitable because of our proximity to Austin.”She said Taylor leadership has updated its comprehensive plan after receiving extensive feedback from the community about how it would like to see the city expand.

Kyle, a city of more than 50,000 in Hays County, is already seeing rapid growth.

“We are on track to have a record year this year, but like all of Central Texas, it has been ramping up for years,” Assistant City Manager Amber Lewis said.

Lewis said the city recently updated its transportation plan and is looking to update its comprehensive plan. But she said the city cannot wait on that plan to begin steering growth to match local leaders’ and community members’ expectations.

In Dripping Springs, city leaders have said they want to maintain the city’s charm in the face of unprecedented growth and get feedback from residents on what that might look like. But, right now, the focus is on addressing basic needs.

“I think there’s some things everybody is in agreement on,” Manassian said. “We all want to move about the city more freely.”