On the days Murray leaves for work, Nathan, a student at Gorzycki Middle School, continues to learn virtually with a pod of other local classmates. Owen, however, needs more support; he attends in-person classes at Kiker Elementary School, where he gets face-to-face instruction from his teachers.

Owen, however, needs more support; he attends in-person classes, where he gets face-to-face instruction from his teachers.

“It’s definitely easier in a physical classroom,” she said. “Learning is really hard for kids that are at home, and teachers have very limited methods of getting a kid’s attention if they aren’t engaging in the class online.”

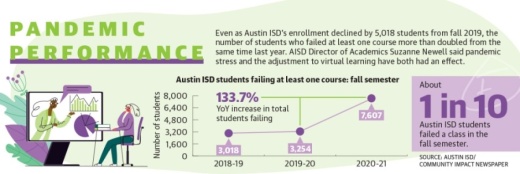

Although Murray said her children have kept up their grades through virtual learning, students across AISD have fallen behind. In the first semester of the 2020-21 school year, 10.1% of AISD students failed at least one course, as compared to 3.2% of students the year prior, according to the district.

“Certainly, those numbers are a concern but they’re also not completely unexpected given the transition that everyone has gone through over the last 10 months,” AISD Director of Academics Suzanne Newell said. “I think it probably could be attributed to any number of factors, the largest of which is students and teachers adjusting to the digital environment.”

Virtual limits

AISD began the current school year offering only virtual classes. and AISD parent Stephanie Carpenter said her eighth grade daughter’s learning suffered because of it. Grades were down, she was not focused and she missed interaction with her peers. That all turned around when she returned to campuses Oct. 5.

AISD began the current school year offering only virtual classes. and AISD parent Stephanie Carpenter said her eighth grade daughter’s learning suffered because of it. Grades were down, she was not focused and she missed interaction with her peers. That all turned around when she returned to campuses Oct. 5.“She was excelling in her classes. She enjoyed getting up and taking the bus and was much happier all the way around,” Carpenter said.

However, on various occasions throughout the school year, the district has stopped offering in-person classes or has encouraged parents to keep students home to slow the spread of COVID-19 in Austin. This inconsistency presents challenges for families and students, and Carpenter said that during these periods of flux, the poor performance returns.

“I’ve seen her remote learning, and I don’t think she is being adequately prepared for high school next year,” she said.

For families, Newell said, the reception to virtual learning has varied greatly depending on students’ age, maturity, interests and previous comfort level with using technology. Students who relied on additional support prior to the pandemic may have had their struggles amplified.

Delia Castillo has three children learning virtually. Her oldest, Bella, is a sophomore at The University of Texas. Although she misses the social aspect of in-person learning and dislikes online classes, Bella said she has learned how to work on the new platform and is excelling.

Castillo said her son, Santiago, a junior and student athlete at Bowie High School, has been less motivated this year, especially without participating in sports. However, she said he understands how important grades are heading into his final year of high school and, ultimately, college.

But Castillo said the spring 2020 semester was a “lost cause” for her seventh-grade son, Benito, who has been diagnosed with dyslexia and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. While things have gotten better during the current school year, she said his success has been directly correlated with how much effort she has put into monitoring his assignments.

The inability to interact with classmates in a traditional setting has affected Benito, and some of the negative feedback on assignments has added to his anxiety, she said.

“It’s really hard to make sure kids like him get what they need,” Castillo said. “His teachers are doing their best, but for someone like my son, sitting on a computer for seven hours is not going to work.”

A widening equity divide

Breakthrough Central Texas, an Austin nonprofit that works with students who aim to be the first in their families to attend college, has been focusing this year on how the pandemic has affected different students across the region.

“Educators are saying it will have a generational impact on academic success for K-12 students,” Executive Director Michael Griffith said. “They’re predicting up to a year’s worth of learning loss at certain grade levels for our most vulnerable students.”

He said the pandemic has impacted those students Breakthrough Central Texas serves—traditionally, individuals of color who come from low-income schools that receive federal Title I funding—by highlighting barriers of health, economic and technology that place students and families under considerable stress.

He said the pandemic has impacted those students Breakthrough Central Texas serves—traditionally, individuals of color who come from low-income schools that receive federal Title I funding—by highlighting barriers of health, economic and technology that place students and families under considerable stress.“It’s undeniable that virtual learning has been a necessary pivot that districts have offered and that families are choosing,” Griffith said. “And it’s undeniable that virtual learning adds additional barriers to equity and additional barriers for access and engagement for some families and students.”

Newell said she hopes AISD’s efforts to provide technology, Wi-Fi and other resources to all students in the district will continue to help more students from low-income families stay connected.

“We have devices for every student now. That certainly was not the case 12 months ago, and I think it is bringing greater equity to student learning experiences,” she said.

Still, Griffith said he has seen the past year play out differently in low-income communities than it has in affluent areas.

Children of affluent families are able to access learning spaces more easily, are more likely to have parents working from home who can provide help, and are more likely to be able to get additional help, including private tutoring, Griffith said.

“Schools in Texas are underfunded, and real solutions would come from having additional advisers and mental health resources to support all students,” he said.

Attendance rates in AISD have declined by 2.7% from this year to last, with more dramatic declines seen at secondary and Title I schools. Increasing attendance depends, in part, on creating stronger student-teacher relationships, Newell said.

“Teachers are being more diligent than ever to be in contact with their students, to see why they weren’t able to get on their device, or even just to check in,” she said. “We have a long way to go to get things perfect, but that has been a priority.”

Sarah Leah Santillanes, chair of the Department of Teacher Preparation at Huston-Tillotson University, said that students who connect with at least one of their instructors are more likely to attend class and succeed. Many of those connections have been stunted this year, she said, but teachers in low-income areas who can reach a student, even over Zoom, will have a noticeable impact in the long run.

Refilling gaps

Educators and parents cannot say definitively what the long-lasting effects of the pandemic will be on students. However, students are still scheduled to take State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness tests this spring. Although schools and districts will not be graded on the results, the STAAR tests will be used to track the losses during the pandemic, according to the Texas Education Agency.

Santillanes said students and teachers across the country have been learning as they go since the pandemic started but are now adapting and improving, a sign that losses could be mitigated this spring.

“Last spring, you had educators that have been in the classroom forever and aren’t comfortable with technology who were scrambling,” she said. “As time has gone on, we’ve slowly learned how to manage it.”

Newell said AISD teachers continue to prioritize lessons essential to carry into the next school year and are preparing to reteach some concepts students may have missed in order to get students caught up. Teachers have also been directed to allow makeup work to prove concepts have been learned. For students who do fail a course, she said the district will look at each case individually to determine if a grade level or class should be repeated.

Aspects of the virtual platform are also here to stay beyond the pandemic, she said, and online tools can help provide additional support to students.

Griffith said he believes it is possible for students to bounce back, and any additional state funding would be key. With that funding, districts could introduce new programs, additional resources and investments in technology that could improve the student experience even beyond the current school year.

“Unless we are equity centric and we’re really focusing our resources to help the schools that need it most, then we’re just going to be perpetuating this,” he said.