While the South Austin-based food bank has been providing groceries for individuals and families for years through mobile food pantries and community partnerships, President and CEO Derrick Chubbs said food insecurity is a growing concern during the pandemic, as prices increase and access has become more challenging.

The food bank has seen a 200% increase in new clients since March, and the large-scale South Austin distribution events are a new way to reach more individuals than before.

“We have people who never thought they would be in that line,” Chubbs said. “Before COVID-19, we had so many people that were a paycheck away [from needing assistance] who have now lost their jobs and need help.”

Families that are food-insecure do not have adequate access to healthy food on a regular basis, according to Seanna Marceaux, the vice president of nutrition, health and impact at Meals on Wheels Central Texas. Factors that contribute to food insecurity include financial strains, geography, a lack of transportation and physical health.

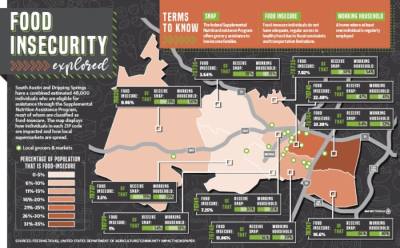

In South Austin and Dripping Springs, an estimated 48,000 individuals were considered food-insecure at the beginning of the year, about 15.3% of the population, according to data by hunger relief organization Feeding Texas.

“Food insecurity is a major social determinant for health,” Marceaux said. “It contributes to malnourishment; is associated with greater health care expenses; and you are more likely to be in poor health, suffer from depression and have limitations on active daily living if you cannot access healthy food.”

Figuring out where need exists

Of food-insecure individuals in South Austin, almost half come from working families.

“Just because you have a car or a home doesn’t mean you have food,” Chubbs said.

Chris King, the CEO of nonprofit Hungry Souls—which works to feed children and their families over the weekend and during school breaks—said unlike many other big cities across the county, Austin does not have one area where poverty is inherently noticeable. Pockets of lower-income areas exist, but surrounded by new construction and high-end homes, it is easy not to notice those who may be struggling.

In South Austin, King said the organization is based out of the Fairview Baptist Church near Stassney Lane, and over the years demographics in the area have changed. As newer properties are being built in the area, lower-income families have moved into the older homes that are slightly more affordable. Many of these families need assistance, and King said the service has seen a 40% increase in demand during the coronavirus pandemic.

Children represent 36% of food-insecure individuals in South Austin, and most of the families Hungry Souls distributes to are working single parents. Hungry Souls has also seen a growing number of grandparents who have needed to step in and take care of grandchildren.

“We have single parents who are working hard, some two jobs, but they’re minimum-wage jobs,” he said. “With the cost of living in Austin, if you have two kids and have to pay rent, utilities, medical expenses, something’s got to give.”

With school campuses closed since March due to the pandemic, Austin ISD has been offering free meals to local children through curbside and bus stop pickup at 70 locations in the district. South Austin is home to 36 of the locations.

“Over two-thirds of our students depend on us for their meals every day,” said Anneliese Tanner, AISD executive director of food services. “School meals are a part of a student’s day, so having that food at home has brought a sense of normalcy.”

Growing needs of homebound individuals

Growing needs of homebound individualsWhether it is due to an individual’s age, physical conditions or a disability, those who cannot leave the home without assistance have faced more challenges accessing food than before. Many are also immunocompromised, which means if they were to leave the home or interact with others they would be at a greater risk of contracting COVID-19.

“The needs of homebound individuals is something that’s popped up like a huge weed during the pandemic, and the number of them is a lot higher than Central Texas Food Bank realized” Chubbs said. “The people and groups that are able to support them traditionally may not be in a position to support them right now.”

Meals on Wheels President and CEO Adam Hauser said that since the pandemic began, his service has added an average of 50-60 new clients per week. Meals on Wheels delivers meals to individuals who are mostly homebound.

“We’ve had a tremendous increase in demand for our services,” he said. “We’ve been able to add a significant number of new clients each week to meet the demands.”

In Southwest Austin, the nonprofit serves 475 homes, representing about 20% of the organization’s entire distribution across Travis, Hays and Williamson counties. There are about 3,000 seniors in South Austin who are food-insecure.

Southwest Austin resident Malcolm Caldwell, who is 100 years old and lives alone, has used Meals on Wheels for the past four years. He said he learned about the program over 30 years ago and appreciated all the hard work volunteers put into serving the community.

“I’ve always been independent and had a pretty structured life, but after my wife passed away, I started becoming more feeble,” he said. “I gave up driving, so I had to depend on outside help. I don’t think I would starve to death [without Meals on Wheels], but I wouldn’t have nearly as good food.”

Increasing food access for all

Similar to how Meals on Wheels delivers food to clients’ homes, other organizations say part of improving food insecurity is making sure individuals have access to healthy food.

Farmshare Austin—which trains farmers and distributes the food they grow around the region through mobile markets—has a mission of “meeting people where they are,” Executive Director Andrea Abel said.

The organization’s markets are placed in Austin’s eastern crescent—including Dove Springs and Del Valle in Southeast Austin—where there are limited supermarkets or healthy options nearby.

While the markets have temporarily closed during the pandemic, Abel said the organization has been delivering weekly orders, targeting low-income families.

“We wish we could do more, because the need is so great,” Abel said. “For people, food access needs have changed recently, and we’re getting so many calls for help.”

Capital Metro has partnered with groups including Farmshare and the Central Texas Food Bank to deliver food during the pandemic. Since March, Capital Metro has distributed over 300,000 meals across Austin.

Capital Metro also partnered with supermarket chain H-E-B to offer free bus passes to those in South Austin with limited transportation options. In June, H-E-B closed one of its stores in South Austin, while opening a new, larger location about 2 miles away. While the new store will serve a greater number of individuals overall, H-E-B Public Affairs Manager Felicia Pena said the partnership with public transit will help those who had been walking to the old location get to the new one.

“As we [prepared] to open our newest H-E-B and close the other, it [was] important for us to be able to find a way to allow those who normally would walk to get to the [new] location,” she said.

Central Texas Food Bank has continued to host its monthly distributions, including in Sunset Valley and Del Valle, and will release a schedule of July events by the end of June.

“Until we see a downward trend in the need, [the food bank] will keep doing this,” Chubbs said.