The pair served pizzas until 2 a.m. every day from a hot, black spray-painted trailer that featured a handwritten menu and an oven that could make eight pies every 12 minutes.

“For us being at a busy bar meant we had a built-in audience from the start,” Zane Hunt said.

He said the pair made $200 their first night, and they knew at that moment they would succeed.

They currently have three brick-and-mortar locations in Austin and three food trucks, including one in Utah. The brothers are planning up to eight more locations in Texas and throughout the U.S.

For the Hunts, food trucks were the only viable foothold in the Austin restaurant business, they said.

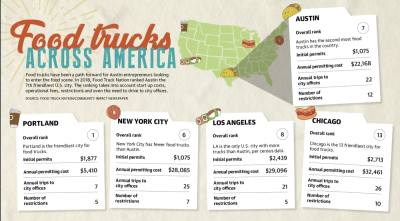

Austin is rated the seventh friendliest city for food trucks nationally, according to Food Truck Nation in 2018, a group run by the National Chamber of Commerce Foundation. The ranking takes into account the cost to run the food truck, the ease of complying with city regulations and other factors. Travis County has the second-highest number of food trucks in the country, only behind Los Angeles County, per 2019 census data.

Currently, there are about 161 food trucks in Austin, according to the Texas Workforce Commission. Several owners spoke to Community Impact Newspaper about their success—from building a community, moving into brick-and-mortar locations to weathering the pandemic.

Starting from the ground up

Happy Lobster, a New England-style seafood restaurant based in Chicago, opened its first food truck in Austin after coming down for South By Southwest Conference & Festivals in 2016. Alex Robinson said operating in Austin and Chicago are completely different experiences.

“Every city I’ve ever looked into or been in, you hear from everyone that it’s food truck-friendly, and then you hear from food trucks that it’s difficult,” Robinson said. “But, I’ve found both cities to be very welcoming to food trucks.”

In Chicago, Robinson said food trucks are mobile and park on street corners to capture lunch crowds or follow special events. In Austin, food trucks typically set up in a lot.

Austin, according to data from Food Truck Nation, is actually more friendly than Chicago for food truck owners, mainly because Chicago’s annual operating permits total $32,461, while Austin’s is $22,168, according to Food Truck Nation data.

The friendliest city, per the report, is Portland, where it costs $5,410 in annual permitting fees to run a food truck. In Los Angeles—the only city with more food trucks than Austin, per census data—it costs $29,096.

“I would give the city of Austin props on how friendly they are,” said Janelle Romeo, owner of Shirley’s Trini Cuisine and a former food truck consultant. “They are very strict with the rules they do have. I have helped other food trucks in other cities and states open, and I’d say compared to those other cities, Austin is on point with the rules and regulations they have in place.”

Chasing the brick-and-mortar goal

Adam Diaz, owner of Thicket Food Park located at South First Street and Dittmar Road, said of all the food truck owners he has met while running the space for trucks, about a third seem to be aiming to open a brick-and-mortar location.

Jae Kim, owner of Chi’Lantro, a Korean-Mexican fusion restaurant that has become an Austin chain, started in a food truck.

Kim maxed out his credit cards and cashed in his personal savings to afford the truck setup in 2010. For about $500 a month, he rented space at Second Street and Congress Avenue.

While Kim acknowledged that rising rent prices are squeezing food trucks owners’ budgets, he said having a prime location allowed him to run lunch services earning around $2,000 a day.

Now the owner of eight Austin-area brick-and-mortars, Kim said the cost of establishing a restaurant is around $100,000 if the space is already set up as a kitchen. It can cost five times as much if the space needs to be completely reworked.

Kim said that price was prohibitive to him when he started a business.

“When I first started, I was in my mid-twenties; I didn’t have any experience working in a restaurant so that people would give me money,” Kim said.

Building community

Francesca Beharry, Romeo’s cousin, works at Shirley’s Trini Cuisine in the Thicket several days a week. She said the effect the business has had has brought her to tears.

“It hits home for a lot of people because they’re from Trinidad and you can see it in their face,” Beharry said. “Older people want to tell you about their life in Trinidad. And some people haven’t had this food in 10 or 15 years, and I’m in here like, should I cry?”

Romeo moved to Austin in 1996 as a teenager from Trinidad and Tobago when her father got a local job in the oil industry. Even as she made friends, she said she still felt like an outsider.

In her early twenties as a single mother, Romeo said she went into finance to support her family. When injuries from a car accident interrupted her work life for a year, she transitioned into business consulting. Then the pandemic hit, wiping out most of her clientele who, as restaurant owners, could not afford nonessential services.

Romeo’s mom suggested she go back to two of her passions: bringing Caribbean culture to Austin and cooking.

“We’re going to bring Carnival to Austin and do all these great things,” Romeo said. “I used to always say, ‘It’s going to start with our food.’”

Romeo opened Shirley’s Trini Cuisine, named for her Trinidadian grandmother. She sold out in two hours. Romeo said she has found a community in Austin through her food truck.

“I have customers who are like friends now because they come every week just to have a sense of self,” Romeo said. “You come to my truck and you can hear our music playing—it’s like a piece of home.”

The pandemic and rising rent

Just a few months after the coronavirus hit the U.S., Chi’Lantro owner Kim remembers turning to his wife and saying, “‘Hey, I think I’m going to go bankrupt. Just letting you know.’”

In the first months of the pandemic, his revenue declined by 80%.

Kim decided to temporarily close two of his eight locations, a food trailer on Congress Avenue and a downtown location at 3030 Colorado St., which have not yet reopened. He told his managers that even if the business went under, he would have enough money to pay all employees for six months before he went broke.

Kim said food trucks had a particular advantage in the pandemic. Romeo agreed.

“Food trucks flourished in the pandemic because people were stuck in the house; they were tired of cooking,” Romeo said.

She said business has been up and down, with the popularity of movements to support local businesses, damages caused by the February freeze and people returning to work.

Diaz said business has boomed for the last year. He did well enough in the pandemic that he is set to build an outdoor-indoor bar that will bring the first brick-and-mortar element to the Thicket food truck park.

“I feel like the pandemic helped our business grow,” Diaz said. “Being outside is a lot safer, and I think people understood that.”

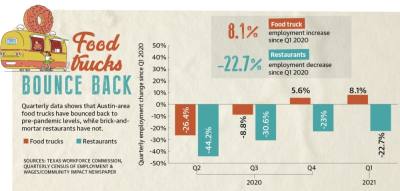

Austin Chamber of Commerce data shows in the first quarter of 2020 there were 142 food trucks with 590 employees. During the next quarter, there were two more food trucks, but about 27% fewer people employed by the industry. Full-service restaurants in Austin lost about 55% of their workforce, according to chamber data. Food trucks also recovered in a way restaurants did not.

By the first quarter of 2021, the number of food trucks grew to 161 and the number of people employed rose to 638, higher than the pre-pandemic baseline. Full-service restaurants, on the other hand, hovered around 77% of the workforce seen prior to COVID-19’s spread, per chamber data.

Despite it helping so many enter the food scene, food truck ownership is not without its challenges. Both food trucks and restaurant owners are facing rising rents.

Kim said the last time he checked the rent for his original parking spot at Second Street and Congress Avenue, rent had gone up to more than $2,000 monthly, over four times what he paid in 2010.

“These parking lots [that] we need to park in Austin, they’re prime real estate,” Robinson said. Adding he is concerned on rising rents will effect food truck owners.

Robinson said he also believes the Austin that the community will rally to support them.

“I think food trucks are such a staple in Austin,” Robinson said. “If it ever came to a point where rent was really starting to threaten the industry in Austin, there would be changes.”

This story was updated to correct that Via 313 originally opened near the Violet Crown Social Club.