“We were actually having the best year ever before this hit. Up until about March 15, we were hitting record numbers,” Hudson said.

Hays County issued its first stay-at-home order due to COVID-19 on March 26, following Travis County’s March 25 order, requiring nonessential businesses, including bars and other venues, to close. The months since have held twists and turns for the local music community. Texas allowed bars to open and host music acts again in late May, only to shutter them June 26 as local and state case counts shot back up. Meanwhile, large arenas have put on shows where masked concertgoers sit 6 feet apart.

A survey conducted in April by the National Independent Venue Association showed 90% of independent venues nationwide could close by fall if conditions persist. Challenges local venues face vary, but industry professionals agree creative approaches are needed for their survival.

“We’re not ever going to give up, but it is very hard to know at this time if it is ever going to fully recover,” Hudson said, “We are not going to go down easy; that’s for sure.”

From virtual to in-person

While venues were closed in the spring, many turned to livestreaming to boost support for the local music industry.“People were ready to get the music back in their souls somehow, and we were able to do that with streaming,” said Clay Hudson, another Hudson’s co-owner.

Treaty Oak Distilling hosted an eight-part “Quaranstream” series that pulled in as many as 1,000 viewers per event, featuring major Texas names such as Ray Wylie Hubbard.

However, Hudson’s success with streaming dwindled as the pandemic drew out longer than expected.

“We still try to keep a livestream going to have some sort of income for the musicians that are always there for us,” Hudson said. “But unfortunately, that’s kind of slowed down.”Venues saw varying success reopening with socially distanced shows in May and June. While small venues, such as Hudson’s, struggled to accommodate state and local social distancing restrictions, some roomier facilities found their footing.

Southwest Austin’s Nutty Brown Amphitheatre held its first shows in June, and regional hub for major acts Dell Diamond kicked back off with a Fourth of July concert for around 2,600 guests—15% of its 17,500 capacity—just after Gov. Greg Abbott issued a mask mandate. Dell Diamond issued tickets to groups and individuals with six feet between them.“What we were really depending on was the fans coming out, being responsible, and they did,” said JJ Gottsch, director of R3 Sports & Entertainment, which works with Dell Diamond and other Central Texas venues.

Treaty Oak, meanwhile, discovered its 26 acres were a boon in the new landscape of live music.

“It’s kind of the sky’s the limit with what we can do with that space,” Treaty Oak co-owner Nate Powell said.Treaty Oak is considering options to host larger events than many other venues have the space for, Powell said, including drive-in concerts and distanced picnic table rentals.As venues mull possible next steps, the Austin cohort of the Reopening Every Venue Safely campaign, a multi-city task force aiming to provide reopening guidance to venues, artists and concertgoers, has issued a guide of best practices, including investing in personal protective equipment and enforcing safety procedures.“We can’t reopen right now, but we need to be prepared for the new normal when reopening happens,” said Bobby Garza, a REVS leadership team member.

Small venues struggle

In addition to struggling with space constraints, smaller, locally owned venues such as Tavern on Main in downtown Buda have faced greater challenges during the pandemic with closures and limited operations because many are classified as bars. In Texas, a business that makes at least 51% of its revenue from alcohol sales is considered a bar.“My passion is the music side, and the beverage side of it pretty much pays the bills, and the food side of it balances everything out,” Tavern on Main owner Julie Renfro said. “There’s a whole category beyond restaurants and bars that follows the same trends.”

Some venues are under pressure in this second closure as rent continues to be due and stimulus payments dry up. Renfro, for instance, opened in June despite her concerns about COVID-19 case counts to make up the rent she had just paid. When bars were again forced to close later in June, some tried to finagle higher food sales to qualify as a restaurant or allow consumption of to-go alcohol on patios. Southwest Austin venue Last Chance Dance Hall’s owners considered these tactics but were discouraged by sluggish to-go food and alcohol orders and exasperation from customers over distancing rules during a brief May-June opening.

“We looked into trying to change our permit, because I think that we could have done that temporarily, but we just didn’t have the response we thought we would [during our re-opening],” Last Chance Dance Hall owner Teresa Parker said. “We thought, ‘Well, we’re going to change it only to not get the results that we’d hoped for.’”Some large venues have been legally required to close as well since Texas restored county governments’ rights to issue stay-at-home orders in early July. Whitewater Amphitheatre has remained closed due to Comal County’s order, eliminating a popular destination for concertgoers in Central Texas and beyond. Whitewater owner Will Korioth said he expects not to hold a full-capacity show until Memorial Day of 2021.

“It kind of looks pretty dismal for anything to happen this year, as far as I can tell,” Korioth said.

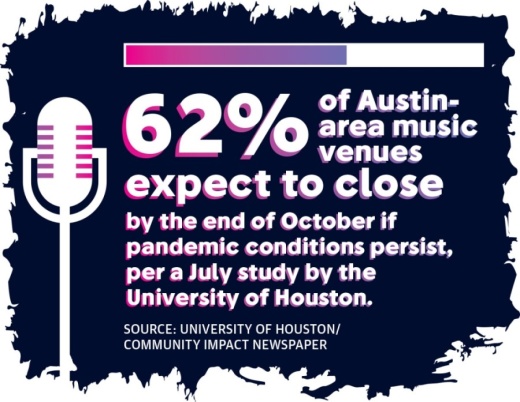

For some, financial pressure and uncertainty over the future has already proven too much. In Austin, a number of iconic venues have closed permanently during the pandemic, including Barracuda, Plush and Threadgill’s final location. A study conducted by the University of Houston on behalf of the Austin Chamber of Commerce in July reported 62% of Austin-area music venues expected to close within four months if conditions continued.

Keeping the legacy of live music alive is vital in Austin and throughout Central Texas, Gottsch said.

“At its core, Austin has always been known as the ‘Live Music Capital of the World,’” Gottsch said. “I really think this entire [metro], from Georgetown all the way down to New Braunfels, is a part of that.”

That legacy is an economic driver. Whitewater’s closure alone for the 2020 tourist season—Memorial Day to Labor Day—means a $60 million loss for the New Braunfels and Canyon Lake area, Korioth said.

Canceling Austin City Limits Music Festival and similar events has also had a profound impact, said Reenie Collins, Health Alliance for Austin Musicians executive director.

“We drive a large part of this economy,” Collins said. “When people come to town, they’re coming in part because there’s so much to do in Austin, and that includes a very vibrant venue music and bar scene.”

Creative solutions

After months of uncertainty, many venue owners say they are still not ready to throw in the towel.“We plan on being around for when the world opens back up,” Parker said.

Gottsch said what it will take for venues large and small to make it through is to “get really creative.”

“The conversations that we’re having with artists, managers, and booking agents are completely different than we’ve had in the past 20 years,” Gottsch said.

At Tavern on Main, Renfro said she is facing her own crossroads of creativity as she decides whether to “give up the ghost” or reimagine her business model, focusing on the food coming out of her kitchen to create the revenue she needs for Tavern on Main to survive.

“I’m trying to figure out what I can do to just limp through. But maybe I won’t limp through. Maybe I’ll thrive,” Renfro said.