Even with this growth, Dripping Springs has not moved to establish its own police department; it relies on the Hays County Sheriff’s Office to patrol the city and its ETJ.

Despite recent population growth, Dripping Springs continues to report a low crime rate. HCSO received 393 calls to service from Dripping Springs in 2019, according to city data, an average of about one call per day. Certain concerns have become more prevalent, however.

“The biggest thing that’s happened with the influx of population in Dripping Springs is greater instances of property crime and more traffic,” Hays County Sheriff Gary Cutler said.

Cutler said traffic on Hwy. 290, a major Central Texas thoroughfare that runs through the city, requires heavy focus from the four deputies stationed in the area—out of 120 uniformed officers throughout the county.

For the time being, Dripping Springs Mayor Todd Purcell says that, even with the increasing hazards presented by the roadway, the time is not right for Dripping Springs to create its own police force. He is certain, however, that it is inevitable.

“It’s not going to be if,” Purcell said. “It’s going to be when. When is the appropriate time?”

The considerations of cities

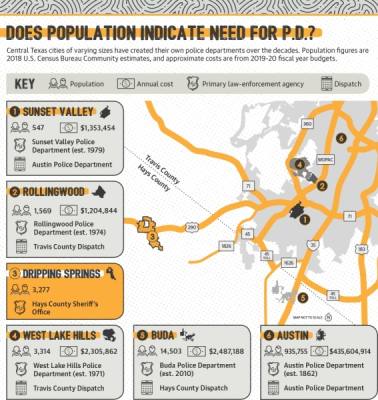

Many smaller nearby cities have chosen to create a police department, including Buda in Hays County, as well as Rollingwood, West Lake Hills and Sunset Valley in Travis County. While local officials have said cost and crime rate are important considerations when determining whether to form a department, other factors are more particular to a given municipality.

Sunset Valley, for example, is in the unique position of being land-locked by the city of Austin. The Sunset Valley Police Department protects the city’s sovereignty and the “local flavor” of its code of ordinances, Sunset Valley Chief of Police Lenn Carter said.

“We like to consider [the department] the wall around Sunset Valley,” he said.

Additionally, Sunset Valley has a much higher daytime population than its residency would suggest—around 12,000, according to Carter—due to Sunset Valley’s extensive retail industry. That makes one of the department’s most important duties to protect “millions of dollars of retail,” Carter said.

The rationale behind staving off a police department can be just as particular. In Dripping Springs, the city proper is only around a quarter of the size of its ETJ, in terms of area, and 9% in terms of population. A police department would only have jurisdiction over the city limits, and according to Purcell, crime in that area is simply not high enough to justify a police force.

“The worst thing you can do is create an entity or a police department or anything just for the sake of creating it,” Purcell said.

For one thing, Purcell said, the costs would be considerable. Annual costs to nearby cities range from around $1.2 million to $2.5 million, based on city budgets, and HCSO Capt. David Burns estimated that department startup costs could range from $700,000 to $1 million.

A neighborhood-highway balancing act

Some area residents, however, say they worry that relying on the sheriff’s office has drawbacks.

“The focus on [Hwy.] 290 safety means that our neighborhoods are not being adequately patrolled,” said Caitlin Fuller, a resident of the Sunset Canyon neighborhood. “I think if we had a dedicated police force, that would help the neighborhood problems and free up the sheriffs to focus on [Hwy.] 290.”

Sunset Canyon does not fall within Dripping Springs’ city limits, but is in its ETJ, meaning it would be outside a hypothetical police force’s purview, but Fuller hopes a police presence in the city would ease the burden on HCSO deputies in her area.

Joshua Visi, a Belterra resident and a police officer for the Austin Police Department, said he recognizes the pressure Hwy. 290 places on HCSO deputies, with whom he cites a positive relationship. Visi shared an incident in which a deputy came to his door to alert him that his garage door was left open.

“I really appreciated him taking the time to get out of his patrol car, come up to my door and let me know,” Visi said.

However, Visi also said the time required by this type of neighborhood spot-checking has a cost.

“The unintended consequence is that the officer is taken away from their other duties, their proactive approach to policing,” Visi said, pointing to the traffic safety demands of Hwy. 290.

While some residents, such as Fuller, have concerns about HCSO’s capacity to strike a balance between highway and neighborhood patrols as the city holds off on creating a police force, many others say they are satisfied with the service they currently receive or favor increasing HCSO’s presence in the area.

“It’s cheaper to hire one or two more dedicated [deputies] than start a whole police department,” resident Charles Thornton said.

Anticipating change

Despite his certainty that Dripping Springs is not yet ready, Purcell said the city remains open to the possibility that a police force will be needed in order to be prepared when the time comes. In his 19 years as mayor, Purcell has met at least annually with the Hays County sheriff to discuss the status of crime and safety in Dripping Springs and HCSO’s functionality in the city.

Most recently, he met with Cutler on Feb. 10, and they again agreed that it was not time to consider an additional enforcement entity in Dripping Springs. In the past, however, Hays County has increased the number of deputies dedicated to the Dripping Springs area, and both Purcell and Cutler said it could happen again.

The city has considered certain transitional measures to soften the ground for the creation of a police force. In Dripping Springs’ Comprehensive Plan, approved in 2016, the city expressed interest in exploring the role of a city marshal. The position would have served as a peace officer who would enforce local codes and regulations while still collaborating with the sheriff’s office.

However, Dripping Springs Deputy City Administrator Ginger Faught indicated the city had retreated from the idea, noting that Wimberley—a similar-sized Hays County city without a police department—had created a city marshal role in 2012 only to abolish it by 2017.

Purcell and Faught said the city has instead made adjustments to certain enforcement positions within the city based on its unique geographical needs.

For instance, after severe floods hit the city in May 2015, Dripping Springs’ part-time emergency management coordinator position became a full-time one. According to Purcell, that position is vital because Dripping Springs is located far from the “epicenter” of Hays County and its emergency management resources.

Purcell said he relies on input from experts, including his emergency management coordinator, to gauge whether the city is ready for a police force. However, he said that, in his own estimation, the city is, “probably four, maybe five years off.”

In the meantime, the community is equally aware that change is afoot in their growing home.

“Dripping Springs isn’t staying stagnant, as everyone knows,” resident Charlene Hardy said. “In time, it will be overwhelming for the sheriff’s office to take care of everyone everywhere in Hays County.”