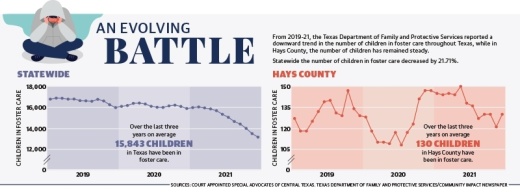

Pandemic-related circumstances—such as children being out of school and out of sight—lead the number of children in foster care to decrease by more than 3,600 over three years.

In December, DFPS reported 13,084 children in foster care statewide, the lowest it has been in the past three years. However, Hays County has not been so lucky.

While the number of children in foster care statewide has slowly declined, the countywide numbers remained steady over the past three years. A number that increased is that of Court Appointed Special Advocates.

CASA of Central Texas serves children in Caldwell, Comal, Guadalupe and Hays counties by offering an additional advocate to the roster of those helping children get placed into a permanent home.

Eloise Hudson, communications manager for CASA, said that while the number of volunteers has continued to increase, they are still only able to serve about 50% of children in need.

In 2020, CASA had 102 volunteers in Hays County and 267 volunteers in all four counties it services. The Hays County volunteers handled 136 cases in 2020, approximately 45% of the cases, according to CASA data.

“Our main goal is to serve 100% of the children,” Hudson said. “Our biggest hurdle is that people hear about child abuse and neglect; they hear about going to court, interacting with the parents; and they worry that they’re not qualified.”

When a report of suspected abuse or neglect is made to DFPS, Child Protective Services steps in and is responsible for investigating the report and removing the child from the home, if necessary, according to DFPS. From there, it is up to CPS to find an appropriate placement for the child. CASA volunteers are not a replacement but rather an aid to CPS, Hudson said.

On the frontlines

Norma Jean Cano worked as an administrator for an early childhood intervention program that aided families of children with medical disabilities.

“That was always so rewarding, being able to help at that level,” Cano said. “Fast-forward to today, I’m still in the field of special education. I work with the Texas Education Agency, and it’s a different role, and it’s great, but it doesn’t get me that direct connection that I was always happy to have.”Cano became a volunteer for CASA in 2019 to give back to her community.

“We were also at a time in our lives where I felt like we had more to give and I felt like there’s so many kids out there in need,” she said.

Cano originally wanted to become a foster parent, but she and her husband knew it would be too difficult for them.CASA advocates receive cases of children who have been removed from their home and, ultimately, the goal is to find the most appropriate placement, Hudson said. However, it is not always possible or can take time. Therefore, arrangements need to be made for children to be in a safe and stable environment while a more permanent foster or adoptive family can be found.

Advocates interview all parties involved in the child’s life, meet with the child at least once a month and attend court hearings to testify on behalf of the child.

Cano received her first case in February 2020 and it closed in July 2021.

“It was a really favorable outcome,” she said. “... His foster placement was great, which made me happy because that’s not always the case.”

The problem with placements

Finding placement for a child is only half the battle. As a former child in the foster care system, Rebecca Welch and her husband have dedicated space in their home to offer a foster home for children in need.

The Welches obtained their license through Caring Hearts for Children, a nonprofit agency licensed and funded through DFPS to provide placement and transitional living to children.

The day the Welches received their license, they provided respite care to a set of twins.

“Anyone can be a respite for a foster family. Respite is like a short-term break for foster parents,” Welch said. “We come in and keep [children] for up to two weeks.”

Respite care services are child care services provided for a short period of time, from 24 hours up to 60 days, according to DFPS.

Over the years, the Welches cared for around 15 children placed with them from 6 months old to a year and a half, and they have provided respite care to almost 10 different families.

They said they usually have two children placed with them at a time, and that comes with its own set of challenges.

Welch said that she has learned to be more flexible as their time being foster parents requires case workers visiting the house, meeting the child’s biological parents and even being notified in the middle of the night of a new placement.

The Welches said they once got a call at 4 a.m. for a child they fostered for a year who arrived at their house with nothing but the clothes they were wearing.The Hays County Child Protective Board provides financial assistance to children in foster care. The board meets once a month to review requests from CPS to help children who were removed from their home with little to no personal belongings, much like Welch’s placement.

Board Chair Lee Ikels said Hays County provides money to children for clothes, medical needs, extracurricular activities and more.

While the board helps supplement the needs of foster families, Ikels said, there is still a gap between removing a child and finding them a foster home as DFPS has reported a rise in the number of children without placement.

Finding a place to stay

From September 2019 to August 2021, the number of children without placement, or CWOP, rose from 53 to 395 with a peak of 416 in July, according to DFPS reports. CWOP are children for whom CPS cannot find a suitable or safe placement and are placed in other temporary emergency care such as a shelter.

Data from DFPS reflects that age correlates with the length of time a child remains without placement: the older they are, the longer they are without.

Children up to age 5 rarely stay without placement longer than a week or two. By the time children reach 13 years old, however, the data indicates that they remain without placement longer due to their higher levels of need.

“Unfortunately, right now, it’s taking a lot longer than what we feel is appropriate [to find placement] for the children,” Hudson said. “There just are not enough appropriate placements. It is [CPS’] responsibility as the state’s arm to take care of those children. We’re trying to help locate the best placement; we can be an aid to CPS ... it would ultimately be up to the state of Texas to make sure that the child’s needs are met [while in] CPS care.”

Lauren Canterberry contributed to this report.