Recent national reports from the New York Times database indicate prisons and jails have quickly become one of the nation’s biggest clusters of coronavirus cases. The number of positive cases among detainees housed at the Hays County Jail and those who have been outsourced, has nearly tripled since June 22.

As of July 30, 106 detainees have tested positive for the virus, which has infected about 24% of the jail’s population, according to the Hays County Sheriff’s Office.

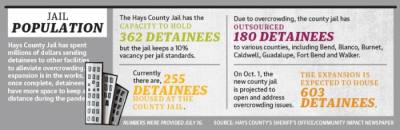

The overcrowded jail cost taxpayers $3.86 million in fiscal year 2018-19 to outsource detainees to Blanco, Burnet, Caldwell, Guadalupe, Fort Bend and Walker counties, but with a •global pandemic in play and no room for detainees to keep a safe distance, the overcrowded jail may come with a higher price tag for detainees: their well-being.

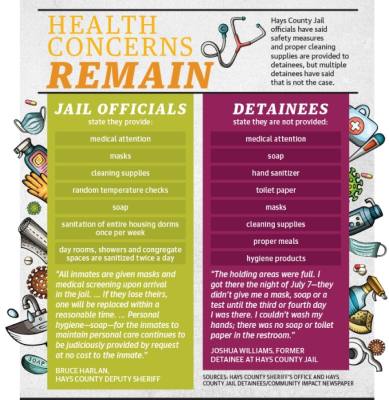

In a statement to Community Impact Newspaper, Hays County Deputy Sheriff Bruce Harlan wrote: “All inmates are given masks and medical screening upon arrival in the jail. If they refuse to take a mask or refuse to wear it, we cannot make them do so. If they lose theirs, one will be replaced within a reasonable time.”

However, several detainees claimed that to be untrue.

“The holding areas were full. I got there the night of July 7—they didn’t give me a mask, soap or a test until the third or fourth day I was there. I couldn’t wash my hands; there was no soap or toilet paper in the restroom,” said Joshua Williams, a resident of Kyle, a cancer survivor and amputee with emphysema, who was taken into custody for a Class B misdemeanor and released seven days later.

“Inmates are provided cleaning supplies daily, and upon request. Personal hygiene—soap—for the inmates to maintain personal care continues to be judiciously provided by request at no cost to the inmate,” Harlan wrote.

Detainees speak about jail conditions

Even after speaking about his pre-existing conditions and compromised immune system, Williams said he did not receive a mask or test upon arrival. Instead, he was placed in a crowded “rec room” where conditions were “filthy.”

“They absolutely knew of my situation, but I didn’t get quarantine until about the fourth day I was in there,” Williams said.

He said he was eventually placed in one of the jail’s four infirmaries, the only place where detainees can truly be quarantined. He also noted that some nurses and the majority of correctional officers were not wearing personal protective equipment.

While he was in jail, Williams said he did not receive a proper meal, and he was denied prescribed medication for his chronic pain, even after getting confirmation from his doctor.

According to Harlan, the majority of detainees who tested positive for COVID-19 were not experiencing symptoms of the virus, and the jail’s medical team routinely monitored those detainees.

Harlan said jail officials issued 250-300 masks a week, but many detainees have not been wearing them in their housing units.

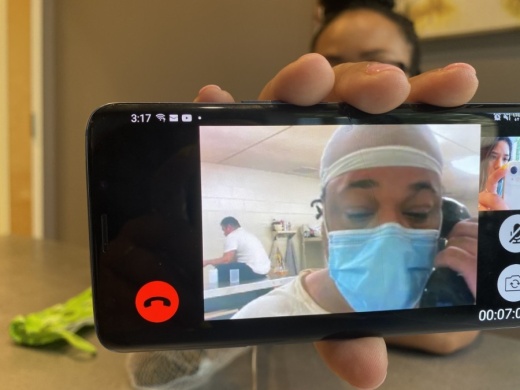

Michael Alexis, a detainee who said he had been in custody for about a year while awaiting court dates, tested positive for COVID-19 in late June. He said he did not receive any medical attention after exhibiting symptoms, including shortness of breath, fatigue and no taste or smell. He said he had been using the same disposable mask since mid-June.

“They just started giving us masks a few weeks ago,” Alexis said.

To Alexis’ knowledge, testing of detainees did not start until June 1, but jail officials contend that testing for the virus began April 24.

“Our medical team routinely monitors inmates. If one of our inmates would experience any symptoms that need medical attention they are instructed—to both verbally and in writing—on how to report symptoms in order to receive treatment,” Harlan wrote in response to detainees’ allegations.

Alexis said he knew of three riots protesting the poor conditions that occurred in June.

Lt. Dennis Gutierrez from the Hays County Sheriff’s Office confirmed that detainees did riot in late June, and the Hays County SWAT team was called to quell the situation.

“They barricaded windows, they tried to set fires [inside the jail], but [riots] had nothing to do with the safety conditions—it was about being tested,” Gutierrez said. “They demanded to get tested right then and there ... there were no injuries.”

Alexis said he thinks following media coverage of the jail’s lack of safety conditions, local TV news channels were censored by jail officials. In early July, he said news channels disappeared, although they still received newspapers.

He also noted an incident in which a page featuring his sisters speaking about the jail’s lack of safety practices was missing from his newspaper.

“Decisions about which TV channels would be available were recently reviewed. As a result, changes were made to add channels that would appeal to the larger population of inmates,” Harlan wrote.

Multiple handwritten letters provided to Community Impact Newspaper through a nonprofit that seeks criminal justice reform—Mano Amiga—revealed that other detainees shared the same experiences as Williams and Alexis at the county jail.

Rick Selman, a detainee who has been behind bars since 2018, wrote in a letter to Mano Amiga about facing delays with his case for the past 15 months. In his letter, he also detailed the lack of masks and proper disinfectant provided by the jail.

“Honestly, masks started to be given on July 1,” Selman wrote in a letter to Mano Amiga. “Few people got masks before, like me, because we found one at work.”

Selman said although guards sanitize twice a day, they use generic Fabuloso and Pine-Sol as a disinfectant.

“I know for a fact because I did the disinfecting of dorms for months,” Selman said.

Neither cleaner is listed by the United States Environmental Protection Agency or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as an approved disinfectant for COVID-19.

According to Harlan, the facility is using Halt disinfectant, a U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved hospital-grade disinfectant.

Multiple other detainees cite in their letters the lack of medication, medical attention and healthy food options to recover from the virus. In a letter, a detainee asks the nonprofit for help and pleads to be deported to his home county to seek medical attention.

Officials consider selective releases

As health experts confirmed prisons and jails are now an epicenter of the coronavirus, some states and counties started to release detainees to slow the spread of COVID-19.

Local activists in Hays County organized demonstrations to demand that pretrial detainees be released amid the pandemic as most of these are victims of a clogged criminal legal system who are sitting in jail for months because they cannot afford bail.

According to Gutierrez, there were about 366 pretrial detainees in a jail population of 435, or 84.14%. That number includes 180 detainees who have been transferred to other counties due to overcrowding.

District judges in Hays County, along with other criminal justice officials, met in March to discuss depopulation of the jail. That led to the release of some detainees, according to Hays County District Judge Bill Henry.

Henry said he could not speak for the rest of the county’s judges, but he has been reviewing his cases for any potential releases.

“I am continuously reviewing my cases on these issues. I’ve made some progress, but there are things on which I cannot approve,” Henry said.

Local nonprofit aids detainees

On the heels of a global pandemic at play inside the county jail, Mano Amiga launched the first bail fund in the county ahead of schedule with grants from the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Foundation and the Bail Project. Bail funds assist detainees who cannot afford their bail.

The nonprofit has helped release about 18 detainees since the launch of the bail fund.

“Pretrial detainees, legally innocent people who have only been charged but not convicted of a crime, account for the majority of our jail population; many of them there because they are simply too poor to afford their own freedom,” Mano Amiga Policy Director Eric Martinez said. “We’re punishing poor community members for their poverty with a fatal virus when wealthy people accused of the same offenses are able to buy their freedom by posting bail and eluding the deadly pandemic.”