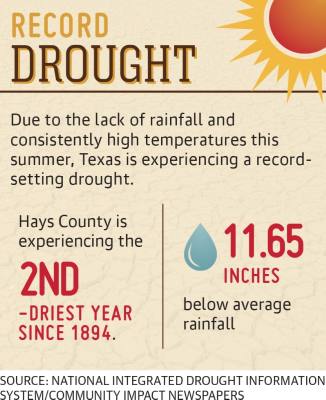

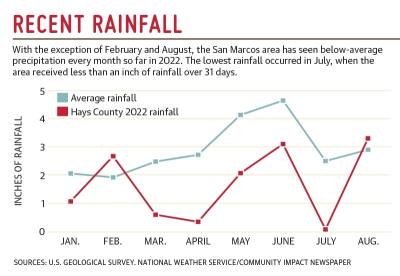

Central Texas may see increased drought restrictions in the future due to a lack of rainfall and high temperatures. As of Aug. 29, Hays County was down about 11 inches of rain so far this year below the average, according to data from the National Weather Service.

While local and regional water suppliers have diversified their supplies over the past few decades by moving away from sole reliance on the Edwards Aquifer for freshwater, more than 2.5 million people depend on the water from Edwards Aquifer, which the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department named one of the largest and most unique aquifers in the world.

The cities of San Marcos and Kyle are under Stage 2 watering restrictions, and Buda is under Stage 1 restrictions. Water levels in the Edwards Aquifer dropped this year to levels not seen since 2014.

The J-17 Index Well in Bexar County is used to monitor and track water levels in the aquifer and correlates closely to flow levels from Comal Springs and San Marcos Springs. The J-17 Index Well is over 23 feet below the historical average values for the summer months in the region, according to the Edwards Aquifer Authority.

It would take a significant amount of rain in the northwest region of Central Texas to allow drought restrictions to be lifted. If the area does not have any rainy seasons leading up to next summer, a dry climate will continue, according to EAA General Manager Roland Ruiz.

“Short of significant rainfall between now and the start of next year, we’re going to find ourselves where we are today except earlier in the year because we may not come out of any stage of critical period if we don’t have rainfall,” Ruiz said.

Drought response

Hays County was free of drought restrictions from June 2021 until March, when officials with the Edwards Aquifer Authority announced Hays, Caldwell, Comal and other neighboring counties entered Stage 1 drought restrictions effective March 9. Stage 1 water restrictions were declared due to the lack of sufficient rainfall and to limit the amount of water that can be used by residents.

San Marcos and Kyle are under Stage 2 restrictions, and Buda is under Stage 1. Some of the restrictions vary from city to city, but generally the restrictions limit watering with a sprinkler or irrigation system to once every week based on the last digit of one’s address, which must occur before 10 a.m. or after 8 p.m.

Jan De La Cruz, conservation coordinator for the city of San Marcos, said the city is constantly monitoring aquifer levels and rainfall to determine the right stage to prevent excess water use or if the stage level needs to rise.

“It’s looking a little bit better lately because we’ve actually been getting some rain. Not as much as we’d like to see but we have been getting some, and some of the recharge areas have been getting some good rains,” De La Cruz said.

De La Cruz said outdoor water use on lawns is the top use of water during the summer, so it is the use most necessary to curtail.

“We try to encourage folks to follow those restrictions and try to educate people that once-a-week watering with sprinklers should be plenty of water for your lawn. It may not be lush green with temperatures and all that, but it’s enough to keep it alive,” she said.

For much of October and November 2021, prior to the current drought period beginning, spring flows at the San Marcos Springs—which is fed by the Edwards Aquifer—hovered above 200 cubic feet per second. As of August, the flows began dipping below 90 cfs, according to measurements recorded by the U.S. Geological Survey.

In neighboring Comal County, the Comal Springs reached a similar peak in the same period, up to nearly 300 cfs in October 2021 and to just below 90 cfs in August.

The most significant historic drought in Texas took place in 1956, when the Comal Springs stopped flowing completely from June to November, Ruiz said. The San Marcos Springs fell to 48 cfs in July of that year.

“The drought that we had from 2011-14 started to look quite a bit like the drought of record [in 1956] in terms of intensity,” Ruiz said. “Some might say that it was even more intense than the 1950s; it just wasn’t as long. In the 1950s, that drought was—depending on who you ask—was either a seven- or 10-year drought.”

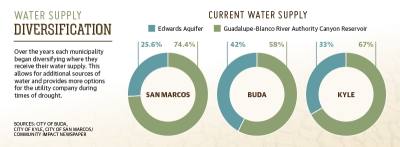

The sources of water for each city in Hays County have also diversified over the years. In 1995, 100% of the water supply for San Marcos was from the Edwards Aquifer. In 2022, 25.6% of San Marcos’ water supply is from the Edwards Aquifer with the Canyon Reservoir and Trinity Aquifer among other sources being utilized. Buda and Kyle reduced their consumption of the aquifer to 42% and 33%, respectively. The Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority runs a line from the Lake Dunlap dam pump station on the Guadalupe River—below Canyon Reservoir—to pump water to each locality.

“[Some local] major users are not solely or wholly dependent on the Edwards [Aquifer]. They’ve expanded their water holdings, and it gives them greater latitude during times of drought like this to have more tools available to manage their various water resources,” Ruiz said.

Water conservation plans

As of Aug. 23, flows at Comal Springs were at about 117 cubic feet per second when the long-term average flow is about 290 cfs, or about one-third of the average, according to Chad Norris, deputy executive manager of environmental science for the GBRA. Cfs is used to measure the pressure and motion of water.

The EAA declared Stage 4 of its Critical Period Management Plan to enforce permit reductions to the San Antonio region Aug. 13. The plan is put in place to help sustain aquifer and spring flow levels during times of drought by temporarily reducing the authorized withdrawal amounts of Edwards Aquifer permit holders, which includes utility companies.

In Stage 4 of the plan, permit holders in Comal, Hays and Guadalupe counties must reduce their annual authorized pumping by 40%.

Norris, who is also a member of the Edwards Aquifer Habitat Conservation Plan Science Committee, said when drought conditions are persistent or spring flows reach a lower output, certain measures of the conservation plan are implemented.

“Some of those measures involve using alternative water sources, reducing reliance on the [Edwards Aquifer] itself,” Norris said. “And those are all designed to maintain spring flows and make sure that they don’t get below a threshold that we have identified as needed to reduce the impacts to [aquatic] species.”

The Comal and San Marcos springs help maintain base flows and are the two major springs that use the Edwards Aquifer and are tributaries to the Guadalupe River system.

Norris said he expects some of the bigger impacts of the drought to be in the smaller tributaries in Texas that do not have springs to provide base flows.

”I feel like in general, we are prepared and not unaccustomed to droughts like we’re experiencing now,” Norris said. “But with every drought, you’re always just waiting for the next rainfall.”

Looking to the future

In August, San Marcos City Council began a discussion of developing an aquifer storage and recovery project inside the Edwards Aquifer, which was passed through the Texas Legislature in May 2019 and that other localities are pursuing efforts on. The efforts could also include various forms of open-space protections in the recharge zone—porous land that most directly sends precipitation back into the aquifer.

“It would be great to pursue our partnerships with the county to look at the value of conservation easements and seeing people that own these large swaths of land, can we make it more valuable for them to hold on to that land and to implement conservation strategies?” Council Member Maxfield Baker said.

Mayor Jane Hughson said she will suggest annexing any land the city owns within the city’s extraterritorial jurisdiction that it already owns to make sure such areas will fall under the city’s land development code.

“I’m going to suggest that one of the things we do is that all the land that we own if it’s contiguous to the city, and we haven’t annexed it—then we annex it,” Hughson said.

De La Cruz said one of the biggest issues with maintaining water use reduction goals is constant communication on water use restrictions.

“One of those things that we always need to do better is just getting the word out and educating folks,” she said.