“It was like this weight was lifted that I didn’t even know I had,” Wright said. “I instantly wanted everyone to feel that way.”

She began by helping a dozen Bee Cave community members find appointments for themselves and their loved ones. Wright was soon flooded with messages from residents, some looking for appointments and some asking how they could help.

In late January, Wright launched Kendra’s COVID Coaches—one of several Central Texas volunteer groups working to aid the region in the pursuit of reaching herd immunity, or the status at which a community at large will have collective protection against a virus. Since January, grassroots groups such as Kendra’s COVID Coaches have helped connect tens of thousands of Central Texans with vaccine appointments.

Incoming requests to the groups have dwindled across April and May, however, and the groups’ approaches have changed to meet people where they are. Kendra said her team has shifted their focus to reaching residents who may be willing to get a vaccine but lack the urgency, time and access to obtain one.

Tammy Crumley, director of the Hays County Local Health Department, said a vaccination outreach program was unneccesary until recently due to demand. Although she believed many people’s opinions about the vaccine were cemented before it became available, she does believe some people on the fence about the shot can be persuaded.

In a survey conducted by Sendero Health Plans across eight Central Texas counties at the end of 2020, 64% of respondents said they would get a COVID-19 vaccine if they had the opportunity. Only 5.5% of respondents gave an unequivocal “no.”

“Those folks are probably not going to change their mind, but there are some that now are thinking ‘well, maybe I should get it for my grandparents or my parents, or travel reasons,’” Crumley said. “You may be able to reach them and have them change their mind.”

Convincing those residents in the gray area is the goal for Central Texas health authorities, volunteer groups and physicians. Working in conjunction to reach these pockets of vaccine hesitant Texans, they hope to boost vaccination rates past the threshold for herd immunity.

In light of emerging virus variants that threaten to upend recovery from COVID-19, there is pressure to reach that goal as soon as possible in what U.S. President Joe Biden has called a “life-and-death race.” As of May 19, around 37.5% of the U.S. population has been fully vaccinated. 58.9% of Americans have had at least one dose, a percentage Biden has said he aims to raise to 70% by July 4.

“We still have the threat of a new variant emerging which eludes those vaccination efforts,” said Austin-Travis County interim health authority Mark Escott in April. “The more we can reduce transmission right now, the more we reduce the chance of new variants, spreading and evading vaccination efforts.”

The road to herd immunity

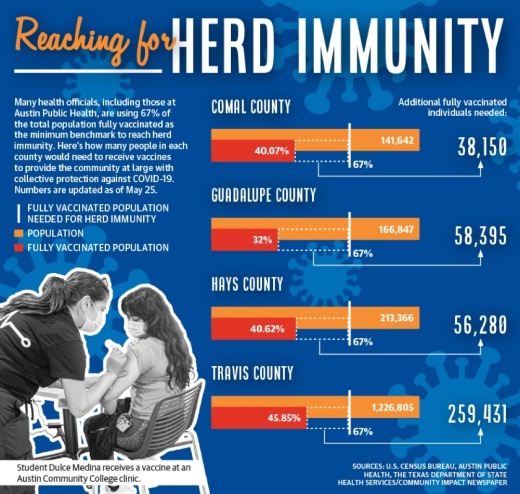

Officials at Austin Public Health have used 67% vaccination of the population as the minimum benchmark necessary to approach herd immunity. But the actual threshold remains unclear.

Anthony Fauci, Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, has estimated herd immunity will come at a higher rate of vaccination, but at an April White House press briefing encouraged people not to focus on specific rates.

“We’ve made estimates that it is somewhere between 70 and 85%, but we don’t know that as a fact,” Fauci said. “So that rather than concentrating on an elusive number, let’s get as many people vaccinated as quickly as we possibly can.”

Other experts, including Dr. Lauren Ancel Meyers, executive director of the University of Texas at Austin’s COVID-19 Modeling Consortium, a network of researchers and epidemiologists, have said that herd immunity is unlikely.

Regardless, Meyers has said publicly that faster vaccination will help the virus subside by reducing the number of infections and community spread of COVID-19 and its variants. Coronavirus infections among fully vaccinated individuals are rare—only around 0.02% have proceeded to catch the virus in the Austin area, according to APH data.

Around 40% of Texans were fully vaccinated as of May 19, according to the Texas Department of State Health Services. Some areas of the state that were hardest hit during the deadliest stage of the pandemic have surged ahead—El Paso, for instance, exceeded 50% fully vaccinated, and has seen the average daily count of positive cases drop by 100 in the past month.

DSHA data show counties in Central Texas still have a long way to go to match El Paso. Travis, Williamson, Comal and Hays counties all have fully vaccination rates at or below 40% as of May 19.

Barriers and hesitation

The FDA’s May 10 decision to expand the Pfizer vaccine’s emergency use authorization to include 12-15 year olds could help close the gap.

Dr. Andrew Cavanaugh, a pediatrician with Chisholm Trail Pediatrics in Williamson County, said his patients have shown strong interest in getting their children vaccinated. Some have also expressed doubts or distaste in surveys, but Cavanaugh said the gradual ramping up of the vaccine’s availability gave patients time to warm up to the vaccine.

“My whole career I’ve convinced people [of] the safety of vaccines and the importance of vaccines,” Cavanaugh said. “I’m kind of glad that the supply has been the way it has. In some ways, I think it's been beneficial, because it has allowed a slow phasing in of this vaccine that people can kind of see what happened to the ‘guinea pigs,’ if you will.”

Vaccine hesitant individuals' reasoning varies. Wendy Penderghast, a 35-year-old woman from Lakeway told Community Impact Newspaper she feels confident her body can fight off COVID-19 if she were to contract it, and has concerns about long-term side effects of the vaccine, although large scale clinical trials have shown side effects mostly to be brief and mild.

Others, however, cited more logistical barriers. Betty Kent, a 65-year-old New Braunfels resident, received her first dose of the Moderna vaccine and had flu-like side effects that caused her to miss five days of work.

“I will not return for the second shot,” Kent said. “No one paid me, and I had to suffer so with my bills, [so] I will just take my chances.”

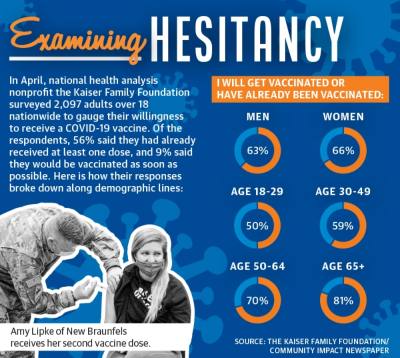

Studies indicate that certain demographics are more likely to be hesitant to get a vaccine. In Sendero Health’s survey, respondents who were women, Hispanic and Latino or economically disadvantaged were all less likely to say they would choose to get a vaccine—although national vaccination data has shown women to be slightly more likely to get a shot than men. Black patients showed the greatest hesitation and were 47% more likely to say they would not get vaccinated.

Katrina Gordon, a family medicine doctor at Baylor Scott & White Health clinic in Kyle, said she sees hesitancy among Black patients that is deeply rooted in a mistrust of the government and health care system related to a history of discriminatory practices.

In Hays County, Black and Latino vaccinations account for 2.49% and 24.15% of shots adminstered, despite representing 4.6% and 40.1% of the county’s population, respectively, according to DSHS.

“We definitely want to see people get vaccinated as soon as possible because we’ve seen, especially in minority communities, that they’re three to four times more likely to be hospitalized or die from COVID-19,” Gordon said.

District 2 Austin City Council Member Vanessa Fuentes has similarly considered what factors will encourage her constituents to get vaccinated. Her Southeast Austin council district is 70% Latino, and much of the hesitancy Fuentes sees among Latinos is the result of misinformation, she said.

San Marcos resident Jessica Fuschak said her main issues with the vaccine were the available data and how information about it is shared.

“It kind of rubs me the wrong way that they are just kind of pushing it so severely,” Fuschak said. “I feel like everywhere you turn—it's like ‘get the vaccine, get the vaccine’—there's so many incentives, and I just I've never witnessed that before.”

Fuschak said one of her primary sources of information about vaccine side effects was the federal Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, or VAERS.

VAERS has a disclaimer stating it cannot alone be used to determine if vaccines are related to adverse events because, in addition to accepting reports from health care providers and vaccine manufacturers, it accepts reports from the public that can be “ incomplete, inaccurate, coincidental or unverifiable.”

Health care providers are required to report deaths to VAERS if they happen following a COVID-19 vaccination, and 4,647 deaths have been reported through May 17. However, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said a causal link to COVID-19 vaccines had not been established.

The CDC did, however, note a plausible relationship between the Johnson and Johnson vaccine and three blood clot-related deaths, or one per 3,441,134 doses administered.

Fuschak also brought up vaccine shedding as one of her concerns, although the scientific community has widely labeled it as misinfomation. The CDC includes information about shedding on a webpage about COVID-19 myths.

Shedding is used to describe a release of vaccine components from those who have recently been vaccinated, but it can only occur when a vaccine uses a live, but weakened, version of a virus, according to the CDC. However, none of the vaccines used in the United States use a live virus.

Though many of her friends and family have been vaccinated, Fuschak said some, like her, remain skeptical, hesitant or opposed to it.

In order to combat vaccine hesitancy, Dr. Emily Briggs, head physician at Briggs Family Medicine in New Braunfels, and other local physicians partnered with New Braunfels Utilities to produce a video addressing myths and misconceptions regarding the vaccine and provide answers to commonly asked questions.

One myth the video addressed is the idea that someone who has previously been infected with COVID-19 has strong natural immunity.

While people who have contracted COVID-19 have antibodies against the virus and may contribute to herd immunity, Escott said they may not be as long-lasting as antibodies from a vaccine, and are around 20 times more likely to be reinfected with the virus than a vaccinated person.

“We have had significantly ill people who have survived the virus then get ill again with another round of it, especially with these variants,” Briggs said. “We can’t consider people that have not been vaccinated to be immune.”

Building access

For some Central Texas residents, accessibility has proven the key to making a vaccine appointment.

In Hays County, Crumley said officials had discussed arranging more mass clinics, but noted the immense resources required to organize and staff them. Instead, she said walk-in clinics would occur as supply allows.

With access in mind, Texas MedClinic, which has locations in Comal and Travis counties, has expanded vaccine appointments at each of its 19 clinics to give residents more opportunities to receive their shots.

“A lot of people simply don’t have the ability to take off from work for an hour or two to get a dose of vaccine,” said Dr. David Gude, Texas MedClinic chief operating officer and practicing physician. “By spreading [appointments] out and hopefully having evenings and weekends, we will be able to reach a whole different section of the population.”

Wright and her team at Kendra’s COVID Coaches, likewise, have gone directly to businesses, reaching out to encourage them to allow residents time off to get vaccinated and recover from any potential side effects, a privilege not afforded to many essential workers.

“When you start feeling like you're probably moving the needle because you’ve helped so many people, you just can’t help but want to do more of it,” Wright said.