Typically, it takes 12-18 months to develop a new vaccine, according to Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. But vaccine researchers—including some in Austin—wasted no time, kicking into high gear in January 2020, before the coronavirus ever reached the United States.

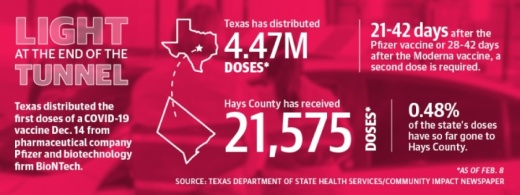

By November, pharmaceutical companies Pfizer and Moderna announced they had produced vaccines with efficacy rates around 95% in clinical trials. After the Food and Drug Administration approved the Pfizer vaccine for emergency use authorization, Texas made its first shipment of more than 224,000 doses of the Pfizer vaccine starting Dec. 14. The FDA followed with emergency use authorization of the Moderna vaccine Dec. 18, and Texas sent another 620,400 doses for health care providers across the state beginning Dec. 21. The Moderna vaccine made up about three-quarters of the second shipment.

As of Feb. 1, hospitals, clinics and pharmacies in Travis, Hays and Williamson counties have received almost 250,000 of those doses for front-line health care workers and nursing home residents, with Hays County accounting for 21,575.

By the end of January, Hays County Judge Ruben Becerra said that though he would like to see larger amounts of the vaccine come with each shipment from the state, he remains grateful for the work local health officials have done to get residents vaccinated.

“Luckily for us, the way we have been running this [county rollout], we have had near zero cancellations,” he said. “Everyone that books [the vaccine] takes it.”

Years in the making

Pfizer’s and Moderna’s vaccines have a strong local connection: Both use a protein developed in a lab at The University of Texas.

Jason McLellan, associate professor of molecular biosciences at UT, sprang into action in early January as soon as the genome sequence was released for the novel coronavirus creating a critical epidemic in China—more than a month before the first reports of COVID-19 in the United States made news. But this was not where McLellan’s work began, his department chair at UT said.

“This is sort of an overnight rapid success that was years in the making. There was a lot of unheralded basic science research that left the scientific community poised to really move fast on a new vaccine,” said Daniel Leahy, the chair of the department of molecular biosciences at UT.

Coronaviruses encompass a large family of respiratory viruses, from the common cold to more serious diseases such as COVID-19. McLellan, along with collaborators at the National Institutes of Health and the Scripps organization, began studying coronaviruses around a decade ago. In 2016, they reported the discovery of a key protein common to coronaviruses, the spike protein, which allows the virus to attack host cells by changing shape.

In the ensuing years, McLellan researched the highly infectious coronaviruses, MERS and SARS. McLellan and his colleagues developed a method to lock the spike protein into its initial shape, promoting the production of antibodies in host cells.

After COVID-19 created an epidemic in China, the McLellan Lab team wanted to be the first to create a basis for the vaccine, but they had no idea the stakes would be so high.

“We were more interested from sort of a basic science standpoint, but within weeks it became clear that the work that we were doing would have much broader implications,” said Daniel Wrapp, a member of McLellan’s lab.

By the spring, the lab began collaborating with Moderna and Pfizer to develop vaccines that were ready to undergo first-round trials. Locally, Austin Regional Clinic helped execute the Pfizer trial. Leahy said nationally, more than 100,000 people tested the vaccine, and according to the FDA, only one individual exhibited severe COVID-19 symptoms.

While the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are the first to arrive in Texas, several others are still in trials. Those vaccines, including one manufactured by AstraZeneca, could be a better fit for rural communities that are hard to reach and do not have ultra-cold storage technology.

Phased rollout

The nearly 2 million Texans who as of late January received a vaccine dose also needed or will need a second dose. For Pfizer, the second shot comes 21 days later. For Moderna, it comes 28 days later.

As the vaccine supply has been increasing, health officials have begun offering it to people at risk of severe illness from the virus, including those over the age of 65 and various essential workers who are not able to work from home.

As vulnerable populations begin to be immunized, it will take time to see a difference in transmission in the wider community, but hospitals should start to see fewer severe coronavirus cases, according to Spencer Fox, the associate director of the UT COVID-19 Modeling Consortium.

“It’s likely that it will reduce the severity of disease we see but not necessarily likely to slow the transmission much in our region,” Fox said. “But it will help to dramatically reduce necessary health care usage, like hospital beds and [intensive care unit] beds, and also mortality overall.”

Dr. Mark Escott, the Austin-Travis County interim health authority, said between January and July most people will be able to be vaccinated, with healthy, low-risk individuals coming later. Children would likely be last in line, and they are also among the lowest-risk groups, he said. Health officials have said the vaccine will be free for recipients, whether they have insurance or not, and so far that has been the case.

Gov. Greg Abbott’s statewide plan stated the vaccine is voluntary, but all the health experts Community Impact Newspaper spoke to recommended vaccination and agreed the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are safe. Reported side effects have predominantly been mild, similar to what one might see from a flu shot.

On Jan. 28, the Texas State Health Department reported more than 1.7 million people had received a version of the first dose of the vaccine, and about 370,000 had been fully vaccinated.

“That is a remarkable accomplishment, and it means that nearly one out of every 13 Texans at least 16 years of age have had a vaccine,” said Imelda Garcia, associate commissioner for laboratory and infectious disease services. “But, more importantly, for Texans 65 and older, that’s more than one out of every six ... who have received a COVID-19 vaccine.”

Garcia said federal vaccine shipments would increase, and as an example reported the total state dispersal was going up from 313,000 in the last week of January to about 385,000 in the first week of February.

There was also a one-time boost of roughly 126,000 first doses from the federal government at the beginning of February, she said.

Hays County was designated what is called a vaccine hub by DSHS on Jan. 16. The DSHS said a vaccine hub is intended to allow local providers more focus on vaccinating areas and populations hardest hit by COVID-19.

As of the beginning of February, state guidelines were still only allowing two groups of people throughout Texas to be vaccinated. Those consisted of frontline healthcare workers and long term care facility residents, labeled 1A, and those over 65 or with a chronic health condition, labeled 1B.

After becoming a state hub, Hays County has held two public vaccine clinics at the end of January. Officials reported high demand from the public during both clinics, and Becerra said he hopes that very soon the county’s portion of the vaccines will increase substantially.

The number of vaccines received by the Hays County Local Health Department only amounts to less than one third of the total distributed, which includes allocations to local hospitals, clinics and pharmacies. As of the end of January, the roughly 21,000 vaccines allocated to Hays County by the state amounts to only about 7% of its approximately 300,000 residents.

Becerra said the county has the ability to vaccinate more people than the amount of doses they are receiving from the state, but officials will continue to create their plans based on the resources available.

“The state is driving this whole thing,” Becerra said. “They’re dispensing the vaccines to us ... and we’re following the state to the letter, to the best of our abilities as professionals in this field.”

Seeing a change

As more people take the vaccine, the country will move closer to herd immunity—the threshold of vaccinations at which an entire population is protected from a disease—but it will likely be months before that happens, Fox said.

So far in Hays County, Becerra said the vaccination effort is going much slower than local officials would like, but he added that there are other paths people can take.

“If you have a relationship with a primary care physician, you should reach out [to them] because chances are very good that they have a batch of doses that they could administer,” he said.

For people who don’t have primary care physicians, Becerra said it’s important to stay vigilant and continue checking with places such as the county health department and local hospitals for availability. Above all, it’s important to get as many people as possible vaccinated in an expedient amount of time, he said.

“Experts generally agree that we’ll need somewhere between 50% and 70% of the population immune before we will reach herd immunity and see the slowing of transmission and kind of get back to life as normal,” Fox said.