The decline in reporting was anticipated with the understanding that they would likely increase when students returned to school or other extracurricular activities, said Christina Green, the chief advancement officer for the Children’s Advocacy Centers of Texas.

In Texas, 175 children are the victims of abuse every day, and 1 in 10 children will be sexually abused before they turn 18, according to statistics from the CACTX.

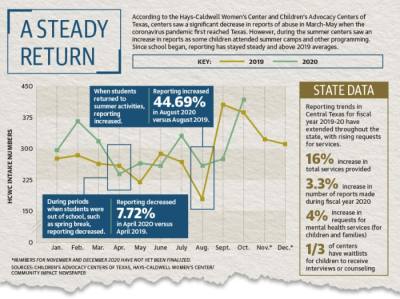

Ahead of the pandemic, year-over-year abuse reporting totals were trending higher in 2020 compared with 2019, Green said. Statewide, 61,891 children were served from Oct. 1 2019 to Sept. 30 2020, up from 59,919 during the period from Oct. 1 2018 to Sept. 30 2019.

“We started to see our numbers of kids coming through our centers statewide start to go up in May and June,” Green said. “Generally, the summer is a slow period because kids aren't in school and they're not around medical professionals ... but we did actually see some kids start going back to summer camps, day camp and some daycares, and so we started to see some of those reports go back up.”

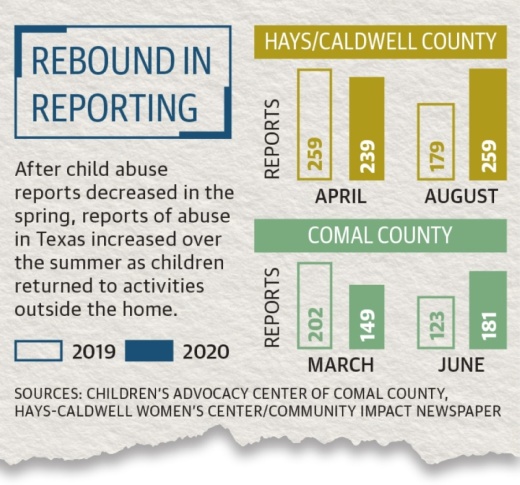

Local data mirror state and national trends, with shelters and crisis facilities in the Hays and Comal County area experiencing similar drops in reporting at the beginning of the pandemic followed by an increase months later.

In Comal County, reports dropped from 202 in March 2019 to 149 in March of 2020, representing a 26.24% decrease, according to the Children’s Advocacy Center of Comal County.

The Hays-Caldwell Women’s Center’s Children’s Advocacy Center, also known as Roxanne’s House, saw an increase of 20.45% in reports from March 2019 to March 2020, but the numbers declined by 7.72% in April.

By June, the CACCC reported a 47.15% increase in reports compared to 2019, and Roxanne’s House reported a 44.69% year-over-year increase in August.

Trendy Sharp, Executive Director of the CACCC, said she expects reports to continue to rise as more children return to school from remote learning and speak with trusted adults.

“We absolutely are seeing the increase,” Sharp said. “I don’t know that we’re seeing the increase that we need to see yet because we’re not back to where we were before [the pandemic].”

Victims of abuse will often wait to report their situation until they are face-to-face with a trusted adult, which leaves them vulnerable to suffer more severe injuries that require medical attention, Green said. She added that during stay-at-home orders, cases of child fatality and emergency room visits related to abuse went up.

Green shared that a staff member at a CAC center in East Texas was conducting a forensic interview with a teenage girl in relation to an allegation of child sexual abuse and learned the teenager’s abuse started shortly after spring break and continued until she was able to return to school in the fall and speak with an adult.

“Generally, with child sexual abuse it’s not a one-time thing, it’s usually repetitive,” Green said. “This child didn’t have anyone safe to tell until she was visibly back in school.”

Adjusting services to meet the need

At the start of the pandemic, crisis centers and local shelters quickly transitioned many services to virtual platforms, while still offering limited in-person services for urgent issues such as forensic interviews and emergency shelter.

CACTX represents 71 CACs serving 210 of the 254 counties in Texas. Centers work with local law enforcement, child protective service professionals and each county’s district attorney to conduct forensic interviews with abuse victims and to provide individual and family counseling while other agencies carry out criminal investigations.

According to the National Children’s Advocacy Center, a forensic interview is a single, recorded session conducted by a professional trained in the NCAC Forensic Interview model in which the child is asked about their experience. The interview is often one of the first steps in an investigation after a report is made and is remotely viewed by representatives of any agency involved in the investigation.

The CACCC traditionally allows safe family members to accompany children to the center where games and snacks are provided before the interview to help children feel comfortable, but those practices had to change this year, Sharp said.

“We always took a lot of pride in families feeling relaxed and comfortable in a home-like environment during a really traumatic time in their lives,” Sharp said. “What we do now is we have as few people as possible on-site for as small an amount of time as possible.”

While masks are required and social distancing is enforced at the center, Sharp said forensic interviews did decline with the drop in reports, and follow-up counseling and family check-ins were conducted entirely online until recently.

“Now we’re doing on-site sessions too, but we’re doing remote sessions as well for kids who feel comfortable doing it that way, or their parents would rather do it that way,” Sharp said. “We're just sort of listening to the families and determining what's best for them, but the type of therapies [are] the same.”

The continual shifting between in-person and remote learning has added a layer of complexity for a child’s counseling, Green said. CACs utilize trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy over 12 visits, and disruptions such as switching between virtual and face-to-face sessions have been challenging.

“It’s that constant balance of where are the kids, and how are the parents managing them being in or out of schools, and what challenges [are those] creating?” Green said.

Serving the whole family

Organizations like the HCWC that offer emergency shelter for adults and children in addition to abuse services also saw a drop in individuals willing to stay at the shelter at the beginning of the pandemic, even when the alternative meant staying with their abuser.

“With family violence, particularly in our shelter, when the pandemic or shutdown first started we did see a drastic drop in people coming out... people were just fearful,” said Melissa Rodriguez, director of community partnerships at the HCWC. “People were calling over the summer, and we were approving them to come in. They just weren’t actually coming in.”

In August, Rodriguez said individuals willing to enter the shelter increased before families began returning to seek support, a trend Ellie Truan, prevention specialist for the Crisis Center of Comal County, observed as well.

“We've been getting a lot of calls, and they're most definitely more severe cases,” Truan said. “We still aren't getting as many people as expected... if you compare phone calls to how many people we have in the shelter, it doesn't match up... people have a greater fear of COVID and the consequences of that, so they almost feel safer staying at home in these situations which is, that's really sad.”

Though calls and shelter stays have risen, Rodriguez and Truan said added economic difficulties and lack of affordable housing make it difficult for families to leave abusive situations permanently.

According to data from the CACTX, 98% of children who experience sexual abuse know their abuser, and 83% are abused by a relative.

Shelter stays at the HCWC average 30 to 45 days, and the nonprofit is currently in the process of building a transitional housing complex on its campus. that is expected to be complete in 2022. The CCCC also expanded its shelter from 40 to 80 beds in September.

In order to interrupt cycles of abuse and violence, it is critical for children and adults to have a way to leave abusive homes and receive the support they need to become independent, Rodriguez said.

“It’s not just the fear of getting sick, it’s also the reality of ‘where are we going to go after shelter,’” Rodriguez said. “There’s not a lot of job opportunities, there’s not a lot of affordable housing. Those are some really big barriers.”

Mental health plays a role in abuse

Increased stress from job loss, health concerns and shifting family dynamics have exacerbated unhealthy situations and increases the risk of abuse, said Jennifer Nieto, Comal County clinic director for the Hill Country Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities Center.

“Family stressors were always a major contributing factor to a crisis,” Nieto said. “If home is not a safe place to be and you remain in your home, that, of course, puts you at a heightened risk for trauma and abuse which can lead to mental health challenges.”

Calls to crisis lines and requests for individual mental health support have increased significantly since March, and families are struggling with the constant change and increased anxiety that accompany the pandemic, Nieto said.

Centers that provide counseling for child abuse victims are also expanding family counseling to deal with daily stress in addition to the challenges of addressing an abusive situation.

“We are seeing a need to do a lot more ... inner familial coaching for parents about how to effectively deal and cope with stress,” Green said. “It's okay to hit your limit and need to take a timeout and to figure out a safe way to make sure your child or children are taken care of so you can take a break and recharge so you don't act out or lash out.”

Combatting mental health on a personal level is critical to maintaining a healthy home environment, Nieto said, adding that creating structure in daily schedules, speaking with a professional and speaking openly with children about mental health are important practices to implement.

As children are interacting with more adults outside the home, it is important for those adults to be aware of signs of abuse and mental health needs, Truan said.

“We’re still doing telehealth... that’s something that we’re going to keep doing,” Truan said. “Even if physically we cannot be there with them, we are going to be with them through the process.”