Whether it is medically or financially, Hispanics nationwide have been falling behind with regard to overall recovery. As one example, an August report from the Pew Research Center showed unemployment among the Hispanic population rose more than the national average at the onset of the pandemic.

Furthermore, a November report from Latino advocacy organization Salud America that analyzed data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that Hispanics were being hospitalized due to COVID-19 at a rate more than 4 times higher than white patients.

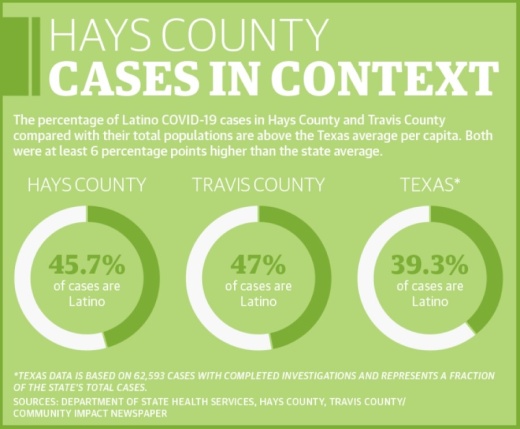

The numbers in Hays County pertaining to the Hispanic population show similar trends.

Hispanics have been infected with the coronavirus at a higher rate than any other demographic group in Hays County by a wide margin, whether by proportional representation or total cases, according to county data.

At least 45.7% of the 7,378 coronavirus cases reported in Hays County Nov. 30—3,371 and counting—were Hispanic community members, which the Census Bureau estimated as 40.1% of the county’s 2019 population.

However, that rate could be higher because 27.5% of all coronavirus cases in the county did not specify their ethnicity. Non-Hispanics, the second largest demographic by case count, self-identified as fewer than 26.9% of cases despite accounting for 52.5% of the population.

Multiple Hispanic community, business and city leaders attribute the disproportionate impact of the virus to the same causes: socioeconomic status, employment type, cultural distinctions and communication strategies from local governments that they said often neglected Spanish speakers.

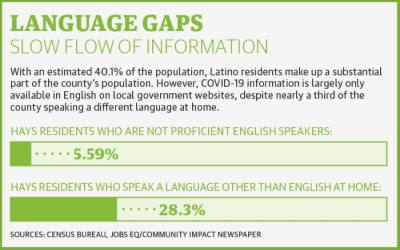

“There is no bilingual health education as far as COVID-19 goes. You will hear many of our [San Marcos] City Council and city leaders say things like, ‘Oh, it's on the city website,’” said Omar Baca, a candidate who ran in the Dec. 8 runoff for San Marcos City Council. “That is where the communication starts and stops. They feel that that is the end of their duty of communicating.”

According to a 2020 report provided by Workforce Solutions and conducted by labor market data firm Jobs EQ, 12,859 Hays residents—5.59%—speak english less than very well. The Census Bureau estimates that more than a quarter of residents speak a language other than English at home.

“If the community isn't communicating to us specifically, we're gonna miss a lot of that data and public health education,” Baca said.

To improve outreach, numerous community organizations throughout Hays County and beyond have become vital pandemic information disseminators.

New San Marcos City Council member Alyssa Garza, who was voted in Nov. 3, has been part of a grassroots effort by nonprofit advocacy group Mano Amiga to deliver testing site information to Spanish-speaking residents using WhatsApp and other messaging services.

Garza said that and other outreach strategies have shown meaningful outcomes with regard to educating the local Latino community about testing and other aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“You saw visually, and you saw it in the numbers, that folks who would have otherwise not been getting tested swarmed the testing sites,” Garza said. “You could visually see trucks of construction workers—like entire sites—coming out after work to all get tested and not being fearful that they didn't have the qualifying ID.”

Baca suggested an additional method the city could implement to improve the reach of communications would be to use roughly 60 EMT workers already employed by the city to share COVID-19 information at churches, schools and other community hubs.

Workforce Solutions was successful with a similar strategy in Hays County. The organization shared bilingual information about unemployment benefits and career training by partnering with a ministerial alliance, food banks and other community organizations this year.

“We've been pretty cognizant to the fact that we have a lot of people in a hurry that don't necessarily speak English as their primary language,” said Paul Fletcher, chief executive officer of Workforce Solutions Rural Capital Area. “We have to put our information in front of them in a way that they can understand it.”

He said the message bearer can also play a role in how successful outreach is.

“When you hear something from somebody that looks and sounds like a government official, it doesn't really penetrate—you don't listen, you don't get the message,” Fletcher said. “But, if you hear it maybe from your pastor on a Sunday morning, and they put a piece of paper in your hand and it tells you how to go take advantage of some of these opportunities—sometimes those things have a little more impact.”

Unemployment ramifications

Hispanics are often employed as frontline workers, according to Baca and J.R. Gonzales, executive vice chair of the Texas Association of Mexican American Chambers of Commerce and executive director of the Buda Chamber of Commerce.

“These essential workers are out there every day being exposed,” Gonzales said.

Throughout the course of the pandemic, data show widespread unemployment has been another unfortunate result within the Hispanic community.

Between March 1 and Nov. 7, there were 1,492 Hispanic unemployment insurance claims filed in the Hays County food preparation and serving industry alone, representing 17.03% of the sector’s claims, according to Workforce Solutions.

In total, 8,765 of 23,589 Hays County UI claims—37.16%—were filed by Hispanics in the same time period.

The CARES Act temporarily provided an additional $600 in weekly unemployment benefits, but expired earlier this year and were not renewed as of press time.

The unemployed now face an end to the national eviction moratorium established in September by the CDC—which halted evictions and is set to expire Dec. 31 unless extended—compounding financial challenges for individuals across all demographics in Hays County.

Exacerbating these struggles, Baca said many low income families may have access to health care in theory, but not in practice. As one example, he listed Immigrants without work authorizations as a group that were not eligible for UI, medicare or medicaid benefits.

“A lot of us refrain from it because one, we don't have health insurance and all those other things,” he said. “Say access—I think that that word is kind of deceptive because it's prohibitive. It's prohibitive to a lot of this part of the community.”

Small business woes

Like the rest of the community, thousands of Hispanic small businesses have been especially hard hit in Hays County, Gonzales said.

“I feel pretty confident saying that, for the most part, Latino- or Hispanic-owned businesses are struggling more because of the added factors,” Gonzales said.

He also noted that much of the CARES Act funding made available to businesses earlier this year was gobbled up by what he described as larger or more agile organizations.

“They [Hispanics] don't have the banking establishments and the lines of credit, or the relationships, that a lot of these other businesses have,” Gonzales said. “We're talking about these small businesses ... they have shoebox accounts.”

When it comes to accessing all of the financial resources that are available to individuals and businesses needing to fight their way through the pandemic, Gonzales and other area leaders again cite a lack of effective communication strategies throughout the community.

Baca pointed to the city of San Marcos website, where the pandemic business resource page is available only in English. While the site does provide a link to a U.S. Chamber of Commerce guide for emergency loans in Spanish, Baca said that information remains woefully inadequate.

“If you go to the city website, you have to know what you're looking for and where it is so you can find the information,” Baca said. “As an acceptable means of communication it’s very poor. It's an F plus at best.”

An audit of the Hays County COVID-19 webpage showed two Spanish links. One led to the website for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—in Spanish—while the other was a document created in March for the county’s expired stay-at-home order.

“We really needed to take an aggressive stance on what we're going to communicate, how we're going to communicate and broadcast a validity of what's being said,” Baca said. “I would hope that we would respond as a government to all the people in our space, because how it goes for one, it goes for us all.”