Texas was a slave state, but Solms-Braunfels went against the grain of most Texans in his disdain for the practice.

“To me personally (and I hope the same is also so for the majority of my countrymen) it is not evident why these men to whom almighty God gave a black colored skin, should belong to others to whom he gave a white skin, to treat as a horse, a dog,” Solms-Braunfels wrote in 1846.

As Solms-Braunfels hoped, slave ownership was less common among Germans, and a slave schedule from the 1860 census, preserved by the Sophienburg Museum, recorded 193 slaves and 26 slave owners in Comal County, which had a population of 4,030.

Guadalupe County had 1,748 slaves and a population of 5,444.

Despite the relatively small slave population, New Braunfels was still shaped by slavery.

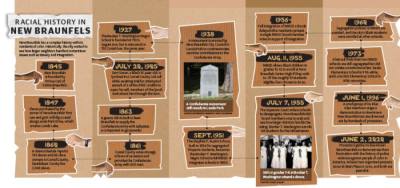

In 1847 or 1848, the American owner of the city’s first grist mill, William Merriwether, owned slaves who dug the canal that runs along Landa Park Drive in order to power his mill.

A byproduct of the canal was Landa Lake, which would be barred to people of color for more than a century after its creation by black slaves.

Split on the Civil War

As secession and the Civil War loomed, Germans in New Braunfels were split on abolition.

Dr. Ferdinand Lindheimer, the editor of the New Braunfelser Zeitung, wrote editorials in defense of slavery and rebuked the idea that Germans had a general distaste for slavery.

“When in Texas, do as the Texans do,” Lindheimer wrote. “Anything else is suicide and brings tragedy to all our Texas-Germans.”

In San Antonio, a group of Germans drafted a statement denouncing slavery and argued states should have the right to ask the federal government to assist states with abolition, according to the book “The Germans in Texas” by Gilbert Benjamin.

From 1853-56, Dr. Adolf Douai was editor of the German San Antonio Zeitung newspaper. He was an abolitionist whose writing supported splitting half of Texas into a free state.

Because of Douai and the convention in San Antonio, Texan-Germans were accused of plotting to turn Texas into a free-state by the Know-Nothing party, a political group that advocated for slavery, white protestant leadership and stricter citizenship requirements.

Many Texan-Germans reacted defensively to the party’s accusations and joined the Know-Nothings despite having personal objections to slavery, Benjamin wrote.

Resolutions denouncing Douai and other abolitionists were signed in the Comal County Courthouse.

“We recommend to our German countrymen to [discount] and suppress attempts to disturb the institution of slavery ...” a resolution stated.

Douai was eventually forced to sell his interest in the San Antonio Zeitung and leave the state, according to the Texas State Historical Association.

In 1861, Comal County voted 239-86 in favor of secession.

“We can truthfully assert that the mass of the Texas Germans are not opposed to slavery,” Lindheimer wrote in an editorial.

According to the book “My Story” by Anson Mills, many Germans in New Braunfels who denounced or voted against secession were lynched.

Persecution during the Civil War

Three hundred Comal County residents enlisted or were conscripted into the Confederate Army, but others resisted conscription or attempted to defect.

Roughly 60 Texan-Germans from the Hill Country made their way toward Mexico to secure passage to New Orleans to join the Union Army, but they were ambushed at what became known as the Nueces Massacre.

Nearly all of the Texan-Germans were killed at the battle or executed.

Giving truth to Lindheimer’s warnings, numerous Germans and Texans believed to be Union sympathizers or abolitionists were hung after trials or fell victim to lynch mobs, according to “Big Wonderful Thing: A History of Texas” by Stephen Harrigan.

According to “Foreigners in the Confederacy” by Ella Lon, hangings of Germans continued as late as April 1865, the month the Civil War ended.

In addition to supplying troops, New Braunfels produced thousands of pounds of saltpeter, a component of gunpowder, for the Confederacy.

A monument to the city’s salt-peter operation was placed in Landa Park in 1938 by New Braunfels City Council.

Several more historical markers memorializing the Civil War were commissioned in 1963, near the height of the Civil Rights movement.

A slow integration in New Braunfels

After emancipation, New Braunfels embraced segregation.

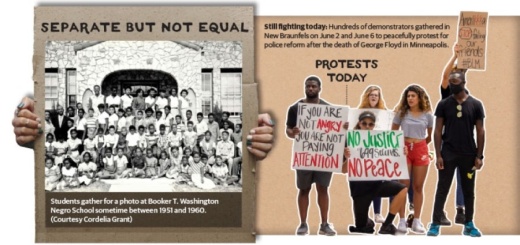

New Braunfels’ first Booker T. Washington Negro School opened in 1927 and was relocated the same year.

The city’s Black children were taught there until the school relocated again in 1951 to the Stephen F. Austin School building, which was built in 1934 for segregated Hispanic students.

After Brown v. Board of Education ordered desegregation of all U.S. schools in 1955, New Braunfels ISD permitted Black students in grades 10-12 to enroll at New Braunfels High School.

Four Black students, among them Kenneth Walker, took advantage of the district’s new policy.

Despite protests from some in the community, Walker said he never experienced serious problems with classmates or teachers and was an athlete.

Full integration of the district took five years. It was first presented to the NBISD school board as a cost-saving measure in 1955. However, the board elected to wait and see how it was handled in larger cities first, according to news clippings from the time.

Integration was postponed again in 1956 due to what a New Braunfels Herald headline described as a “storm of protests.” In a Herald article published July 13, 1956, school board member C. W. Heitkamp warned the board “not to get ahead of the pioneers.”

Heitkamp opposed integration and rejected closing Booker T. Washington. He suggested residents would pay to keep the all-Black school open.

However, when the district was fully desegregated in 1960, Booker T. Washington was closed due to the considerable cost estimates for repairs and updates needed to bring it up to the same standard as the district’s white schools.

Absent from New Braunfels were demonstrations for civil rights.

“When I left [for New York], the population here was 16,000, and [Black residents] were 1%,” said Cordelia Grant, a Black woman raised in New Braunfels during integration. “What could you do?”

The sentiment was shared by Walker, and both said their families were too busy trying to survive.

“There was no such thing as going out to restaurants like everybody does now, so you feel the impact of certain places you couldn’t go,” Grant said.

When Walker left New Braunfels in 1958 to join the Navy, much of the city was still segregated.

“We could not go to Landa Park; we could not go to [Main] Plaza,” Grant said.

At Brauntex Theater, people of color were relegated to balcony seats.

De facto segregation continued for many more years in parts of town.

In 1973, a lawsuit found that students at Seele Elementary School were 91% white, and Lone Star Elementary School was 95% minorities.

The court ruled that NBISD did not break the law because students attended the school closest to them.

Representation in 2020

Due to the small ratio of Black New Braunfels residents—2% Black and 2.5% mixed race in 2019, according to the Census Bureau—representation and visibility has been an ongoing challenge.

George Green became New Braunfels’ first Black City Council member in 2013 but vacated his seat in 2017 to pursue an elected position for Comal County and was defeated.

In recent months, the subject of justice and equality has received renewed national attention after the death of George Floyd, a Black man killed while in the custody of Minneapolis police officers.

Hundreds of demonstrators gathered in downtown New Braunfels on June 2 in solidarity with worldwide protests for police reform. Another group of peaceful protesters arrived in Main Plaza on June 6.

These were the first large rallies in support of the Black community in New Braunfels since 1996, when a few hundred protesters gathered to oppose a small Ku Klux Klan rally.

The general opinion of protesters, Grant and Walker was positive toward the New Braunfels Police Department, but several protesters alluded to issues they had experienced with the Comal County Sheriff’s Office and the Comal County Jail.

“We need to sit down nationally with the authority, with the chief of police, the mayor and let them know that ... if you do things that are contrary to the law, you’re going to be prosecuted.” said Henry Ford, founder and vice president of the New Braunfels Martin Luther King Jr. Association.