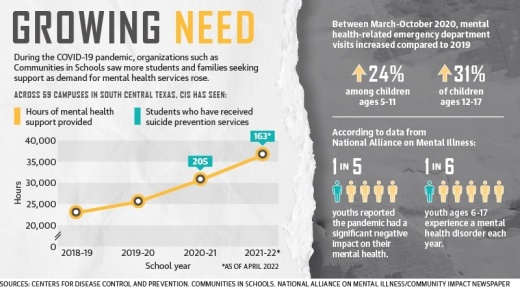

Data from the CDC also showed that, compared to 2019, the proportion of emergency department visits that were related to mental health increased by 24% among children ages 5-11 and 31% among youth ages 12-17 in 2020.

In the wake of the pandemic as children return to school and social settings, mental health providers throughout Central Texas have seen a sharp increase in demand for services for children as diagnoses of anxiety, depression and behavioral issues rise.

“I have noticed the anxiety like never before, and [children] are not really sure where it’s coming from,” said Cindy Cattin, a licensed professional counselor at New Braunfels High School. “They can’t pinpoint where it’s coming from, but they need our space. They need somebody to talk to.”

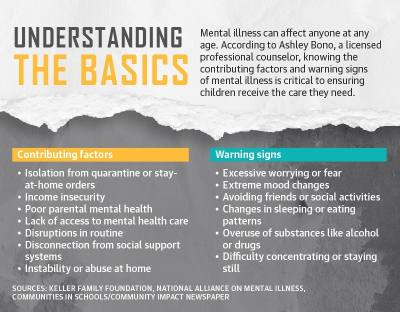

Cattin and other mental health professionals have pointed to prolonged isolation during school closures, uncertainty related to the COVID-19 pandemic and increased access to social media as some contributing factors to rising rates of mental illness.

As the need for access to mental health care continues to mount, local school districts, nonprofit organizations and private practices are working to hire additional staff to meet the growing demand.

Even as awareness about mental illness continues to increase and seeking treatment is further destigmatized, some providers such as Dr. Anne Esquivel, president and founder of the local children’s counseling practice Mind Works, expects the need for support will continue to outpace the number of available practitioners.

“I don’t think anybody has enough staff to be able to meet the needs,” Esquivel said. “The repercussions of this two-year period are going to be long-lasting. And just because the pandemic is done does not mean that the trauma is gone ... every single person in this world was impacted in some way by the pandemic.”

Listen to hear the reporter of this story share more insights on mental health challenges in Central Texas on the June 10 episode of The Austin Breakdown.

Communication challenges

According to a report from the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonprofit organization that focuses on national health issues, parents with children ages 5-12 reported their children had elevated symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress during the pandemic.

Additionally, a study conducted in October 2020 by the Pew Research Center showed that 47% of parents of children who were preschool age or younger were more concerned about their children developing social skills than before the pandemic.

“Clearly, the isolation that was created as a result of the pandemic as well as the increased screen time has not helped our kiddos to learn those social cues and those communication tools that are just necessary to live in the world,” said Ingia Saxton, executive director of secondary schools for New Braunfels ISD.

As a result of school closures at the beginning of the pandemic and changing mask mandates from district to district, Saxton said students have become more reliant on technology for communication and have struggled to readjust to in-person interactions.

Communication barriers created by technology are a driving factor behind rising anxiety and depression, said Sasha Gomez, a licensed master social worker at Comal ISD’s Church Hill Middle School.

“Kids are just spiraling like they feel like they can’t talk to their teacher about turning in a piece of homework or things [that] I think, developmentally, middle schoolers should be able to communicate,” Gomez said. “That social communication aspect is just really impacting how anxious they feel about school stuff and home stuff.”

The changes in mental health needs among students has impacted the way campus staff approach education, Saxton said, and partnerships with organizations such as Communities in Schools have created opportunities to educate teachers about how to support students who are struggling.

Both NBISD and CISD partner with CIS of South Central Texas to provide additional support on campus, and Cattin and Gomez have each been involved with the organization for a number of years.

According to CIS of South Central Texas, the time spent providing mental health support to students and families across 59 schools increased from 22,932 hours during the 2018-19 school year to 36,605 hours during the 2021-22 school year as of April.

At NBHS, a group called Unicorns in Action was formed to bring about 40 students together each week to discuss communication, coping skills and more, Cattin said.

Both Cattin and Gomez said that continued education about mental health for students and adults is needed in addition to greater access to support.

“I think there’s always still work to do with destigmatizing mental health and what that looks like for each person,” Gomez said. “Everyone is struggling in some way, and it’s OK to talk about it.”

Tackling accessibility

While school counselors and mental health professionals on campus provide significant support and crisis intervention, students who need long-term care are often referred to external counselors and other community resources, Gomez said.

“We do a lot of short-term solutions in school because we want them to be in class as much as possible,” Gomez said. “We’re one person that’s potentially servicing a whole school.”

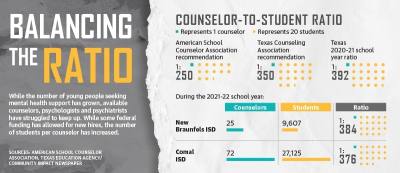

The American School Counselor Association recommends one school counselor for every 250 students, while the Texas Counseling Association recommends one for every 350 students.

In NBISD, the current ratio is approximately one counselor for every 384 students, and CISD has about one counselor for every 376 students, according to district data. During the 2020-21 school year the state of Texas had one counselor for every 392 students, according to data from the Texas Education Agency.

Area school districts have partnered with organizations such as Hill Country Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities Center, or MHDD, and Connections Individual and Family Services to connect students with providers. As of May 19, Hill Country MHDD has received 110 youth intakes in Comal County since January, according to Jennifer Nieto, Comal County clinic director for MHDD. The clinic received 79 intakes during the same period in 2021 and 78 in 2020.

“We are always lacking access to psychiatrists, especially for children in our community, like the waitlists can be months,” Gomez said.

In addition to partnerships with these organizations, CISD has also contracted with 13 individual and group therapy practices to provide services on campus for more than 300 students, said Kristi Elliott, director of student support services for CISD.

While campus programming has grown, referrals have also increased, and waitlists to see area providers have grown significantly.“These kids need support, but resources are very limited,” said Ashley Bono, a licensed professional counselor at InMindOut Emotional Wellness Center. “Now the need for therapists and psychologists and mental health professionals has skyrocketed, and we really don’t have a lot of people to meet that demand.”

Bono said the pandemic added to the already growing demand for mental health care. Since 2020, Mind Works has opened three new locations in Central Texas, and Esquivel and her team are working to hire more staff. Each location has a waiting list.

Mental health providers also discussed the importance of teaching coping strategies and communicating with parents to equip children with the tools they need to maintain their mental health post-treatment.

“The majority of parents that are in our practice are highly invested in the well-being of their children,” Esquivel said. “We want to teach those coping skills that the child and the parents need and then to be able to help them move on.”

Creating solutions

As local providers work to hire more staff, NBISD and CISD have also made strides to strengthen their student support programs.

In 2020, CISD combined the school safety team, school resource officers, health services and licensed mental health professionals to create the CISD Department of Safety and Student Support, Elliott said.

The district also increased its mental health staff from four social workers to 19 licensed mental health professionals, she said.

At NBISD, officials allocated Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief grant money to create four new counselor positions and six new Communities in Schools positions, according to the district.

“We’ve been able to get some good counselors and hire some more counselors to help us out,” Cattin said.

Additionally, NBISD announced April 25 that Kelley Shipman has been hired as the district’s first director of counseling. Shipman is serving as an assistant principal at New Braunfels Middle School and will begin her new role July 1, Saxton said.

Shipman will work with campus counselors and Communities in Schools staff to support their work, Saxton said, and will oversee efforts to increase the health and well-being of students and staff and will develop models of support in times of crisis, loss and grief.

In summer 2021, the Suicide Prevention Council of Comal County was formed to provide support to community members and assist residents in finding care, Nieto said, and the council is registered with the state department of health and human services.

Nieto serves as chair for the council.

“The council is made up of community members, different organizations, businesses and survivors,” Nieto said.

Though MHDD is understaffed, Nieto stressed the organization can still receive new patients and refer them to the best provider if MHDD is not the most appropriate option. The organization also created the website www.mapcomal.org where residents can find help and learn about support options available locally.

Despite staffing challenges and growing mental health needs, area providers are hopeful that continued education and collaboration between the community and professionals will make a difference.

“There are definitely people who want to do this work, who have the heart to do mental health work or be in our schools,” Gomez said. “It takes a team effort. We’re not working in silos.”