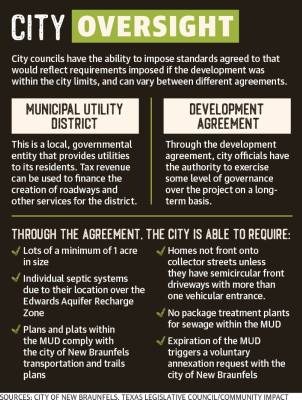

MUDs are one of many special-use districts cities or counties can authorize within the ETJ for developers to finance utilities and infrastructure for new subdivisions and other developments. More than 2,700 acres of proposed new development just outside the city limits have led to the requests to create such entities.

MUDs tend to be used for the purpose of creating developments outside of a city’s limits where utilities might not be readily available, and create a taxing or fee system for new residents to pay for connectivity. They are one of many types of special-purpose districts, which are the most numerous units of government in Texas, according to the Texas Public Policy Foundation.

“A MUD is just one of several different types of special districts allowed by state law that is a tool that a developer can use to help them finance the cost of roads and sewer lines and water lines,” said Christopher Looney, planning and development services director for the city of New Braunfels. “Once it’s created, the MUD is then managed by a board of directors. They’re elected from the people who live or own businesses within that MUD. The MUD then levies their own taxes and fees on themselves to then repay the developer for their costs,” he said.

The amount of city of New Braunfels staff time and expenses associated with the applications led the council to begin the process of implementing fees for applications, settling on a figure of around $18,000 per application, initially authorizing the fees at a July 25 meeting.

That price point is within the range of the application fees required in the cities of San Marcos and Denton. Some cities in Texas—such as College Station—charge over $30,000 for the application fee.

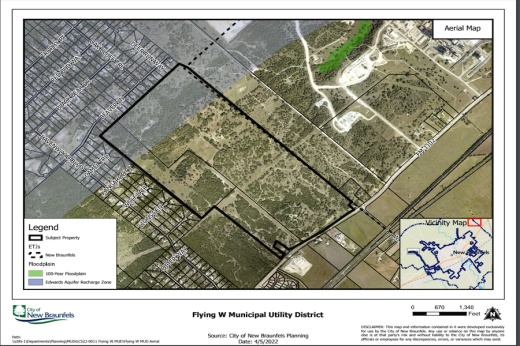

The council began the process of considering the fees earlier in the summer after two MUD applications—the Flying W MUD, a 362-acre development at the far northern end of the city’s ETJ near the corner of Hunter Road and Watson Lane, and Guadalupe County MUD No. 5, an almost 300-acre proposed development off FM 725 near the Bandit Golf Course—ended negotiations between the developers and city with no resolution and council denying the applications.

“One of the things that we have addressed on a couple of these is the fact that we need to be compensated somehow by the developers to be able to have our staff come up with the right message and the right requirements to be able to provide developments that all of us in New Braunfels, Texas, want,” New Braunfels Mayor Rusty Brockman said. “A lot of the stuff that’s been presented to us is not something that New Braunfels needs or wants.”

Creating the ETJ system

According to the Texas Legislative Council, a nonpartisan agency that provides research for the Texas Legislature, ETJs were created in Texas in 1963 by the Texas Legislature to formalize the process by which cities would annex unincorporated areas near their border as they grow.

“In 1963, the Legislature, for the first time, tried to put in place some really standard procedures on how annexation should take place as well as creating this concept of extraterritorial jurisdiction for the first time,” said Trey Burke, an attorney with the Texas Legislative Council at a Sept. 13 Texas Senate committee hearing on local government. “When we talk about extraterritorial jurisdiction ... it is this band of land that surrounds the corporate boundaries of a municipality. Law is pretty clear that this has to be an unincorporated area so it’s not an area that’s part of another city. The law is clear that it has to be contiguous so that the band stretches out from the boundaries itself.”

Burke said in his testimony that this effort was meant to establish some standards on how cities can regulate development within boundaries that they might eventually be compelled to annex, but with limitations.

“In this external jurisdiction, it’s not the same as within the city where clearly the city has lots and lots of authority. Their authority is really fairly limited to what they can do. There’s some regulatory authority; there’s really no taxing authority,” he said.

The developments in the New Braunfels ETJ that have applied for these special-use districts can be found on all sides of the city’s boundaries, in some cases on the boundaries of the ETJs of other cities, such as Seguin and San Marcos.

Regulating the development

While a city must give its consent before the MUD may be established—a formal nod that allows the developer to initiate proceedings to create the MUD through the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality—cities typically expect higher standards and practices than what might occur without the MUD, at least according to the city of New Braunfels. If a city does not consent within 90 days, state statute allows the property owners 120 days to work directly with utility providers before they appeal to the TCEQ for final consideration.

Looney said within the negotiations, the city can insert elements of its comprehensive development plan to ensure goals such as landscaping, lot size and density, sidewalk design and other items the city considers important are part of the new developments.

“There’ll be some negotiation. Some of the things that we do like to include in the development agreement are requiring the applicant to obtain building permits,” Looney said.

Appealing to the TCEQ is the next step for both the Flying W and Guadalupe County No. 5 MUDs, which did not get approval after council hearings and city staff negotiations.

“We wanted the developer to cut the density, especially in the area above the recharge zone of the Edwards Aquifer,” Brockman said. “None of us think that it’s a good thing for the recharge zone to be covered with lots of impervious cover and concrete and other things.”

Changes on the horizon

Regulatory authority could change during the 2023 Texas Legislature’s session, set to convene Jan. 10.

The Texas Senate committee on local government has been hearing ideas at September hearings on changing the approach of cities to influence ETJ’s and the almost 60-year-old structure’s relevance.

The issue is—among other things—determining who is in charge, as often counties and cities both try to exert control over ETJs, something that developers and eventual residents of the communities find difficult to maneuver, according to testimony from Scott Norman, executive director of the Texas Association of Builders, in a Sept. 13 hearing.

“We had blatant examples where the city requires, for example, bike lanes, and the county says, ‘We not only don’t require them, we prohibit them.’ ... Our members are telling us we really don’t care. We want one set of rules. We cannot comply with conflicting requirements,” Norman said.

While that system can be frustrating for developers, ultimately cities do not have many avenues to prevent growth outside of their boundaries altogether, as developers can continue to appeal up the government chain.

“Texas is pretty flexible with growth. They don’t let cities kind of stop it, if you will. ... Our comprehensive plan can’t control the speed with which property owners want to develop their property,” Looney said.

For prospective residents, representation in local government also becomes an issue. James Quintero, policy director for the Texas Public Policy Foundation, said at the same hearing that ETJs serve as an example of where residents live with local government actions without voting power.

“Under current law, residents of the ETJ are denied the right to participate in local democratic elections, which thereby deprive them of the opportunity to vote on those who govern their day-to-day lives,” Quintero said.