Once complete, the project will provide residents and industry professionals with clear guidelines for new and existing developments that align with community priorities in the city, according to the city.

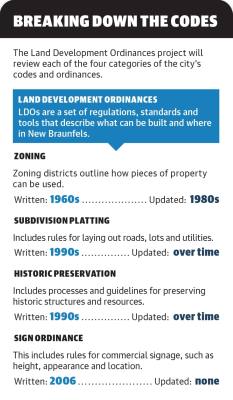

The land development ordinance, or LDO, is an 18-month-long project focused on rewriting the city’s zoning, subdivision platting, historic preservation and sign ordinances, according to the city.

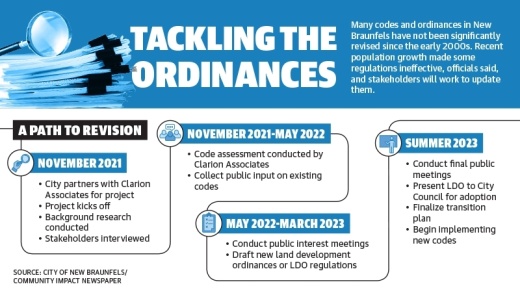

The update was recommended by residents during the creation of the 2018 Envision New Braunfels Comprehensive Plan, said Christopher Looney, planning and development services director for the city. As part of the project, the city contracted with Clarion Associates, a national city planning firm, to evaluate the ability of current codes to implement the city’s Envision New Braunfels comprehensive plan and develop the new code, Looney said.

In May, Clarion finalized an initial assessment of the current code that outlined primary recommendations and goals titled the Code Assessment Report. The report took into account more than 700 community responses to a survey conducted in January, Looney said.

“It’s really important to make the code easier to understand and to use and to provide a tool to implement Envision New Braunfels,” said Matt Goebel, project manager with Clarion Associates, during a June 3 public input meeting. “You’ve had incredible rapid growth and change. ... So a new code is a [really] important goal for the city to help make growth more predictable for people that live here, for people that want to develop here.”

Originally written in the 1960s and updated in the 1980s, the zoning ordinance includes zoning districts that separate activity and development by compatibility. Similarly the subdivision platting, historic preservation and signage ordinances were written several decades ago and have only received piecemeal adjustments in recent years, Looney said.

Looney gave current efforts to implement sidewalks as part of the comprehensive plan as an example of changes that are hindered by the rule that properties are only required to install the feature when land is replatted.

Additionally, some homeowners have been required to go through an often expensive replatting process when renovating or building an addition to their home, he said, which is another issue that will be addressed during the project.

Gathering input

Representatives from existing city groups, such as the historic landmark and planning commissions, will work with individuals from a variety of related industries to evaluate the new code, Goebel said.

“[The code] reminds me of a house when you have more people join the family, you just add on another room and after a while, it makes no sense, no logic to add to an existing old house,” said Johnnie Rosenauer, a retired professor of real estate at several universities in Texas and member of both the Workforce Housing Advisory Committee and the LDO citizen advisory committee. “As we’ve exploded, we just need to create a new system.”

According to recent estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau, the population of New Braunfels jumped to more than 98,000 residents as of July 2021, up from approximately 56,080 in 2011.

As the city continues its rapid expansion, Rosenauer said it is critical the remaining available land be utilized effectively to align with usages outlined in Envision New Braunfels, such as affordable housing, community space and walkable neighborhoods.

In addition to creating standards for new development, the LDO will also re-evaluate the historic preservation codes to better protect historically significant buildings and neighborhoods throughout the city.

Tara Kohlenberg, executive director of the Sophienburg Museum and Archive and a lifelong resident of New Braunfels, said she is hopeful the new code will clarify historic preservation ordinances and outline how they will be enforced.

“One of the things that makes New Braunfels so wonderful is the historic downtown. That historic downtown has taken work to preserve it,” she said.

While four historic districts exist in the city, Kohlenberg said the current codes do not provide adequate parameters for changes made within them and do not appropriately protect structures, features or heritage trees.

Tailoring historic district preservation standards to each district and allowing city staff to make decisions on minor projects instead of sending each request to the historic landmark commission are a few possible changes that could be made to the historic preservation code, Goebel said.

“The story of how we got here and how New Braunfels grew to be what it is, is important. It tells the story of the people. ... Historically, that’s important. That’s part of the story. And I think those things need to be protected,” Kohlenberg said.

She added that she hopes the revisions will be clear, concise and not open to excessive interpretation.

Jumping into zoning

Following the completion of the Code Assessment Report, the city hosted several public input meetings focused on each of the four sections of the code.

Officials, Clarion Associates and the committee will approach the sections in phases, Goebel said, with the first being zoning.

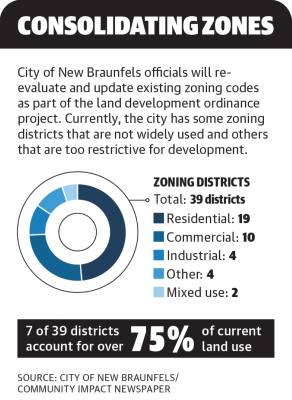

According to the assessment report, the city has 39 unique zoning districts and 73 additional special districts.

By comparison, San Marcos has a total of 47 zoning and special districts, and Schertz has 30, according to city documents. “While we wouldn’t ever say, ‘Oh, you know, the right number of zoning districts for a city of your size is x.’ ... 39 is kind of a lot,” said Jenny Baker, a project associate with Clarion. “One of the reasons why there are so many is that there is this slate of pre-1987 districts, and then a slate of post-1987 districts. In many cases those are the same.”

The zoning ordinance received some updates in the 1980s, Looney said, but many duplicate zones remained in place.

Over 75% of current land use falls into one of seven districts while 24 districts account for less than 1% of land use, Baker said. One of the primary goals of the LDO project will be to simplify the districts by combining duplicate districts, maintaining frequently used districts, eliminating unused zones and creating new districts that better fit the city’s needs, she said.

After each phase of the project the city will host additional public meetings and surveys before moving on to the next phase, Looney said.

Once the project is complete, the team will present each portion to City Council for approval and develop a plan to determine enforcement and how existing properties will be incorporated.

Though the timeline for the project is long, Looney is hopeful the project will result in a code that streamlines city processes and allows for better flexibility and adaptability in the future.

“I believe if we can have a clear set of instructions, a recipe book that says here’s the things you need to do, and here’s examples of those. ... I think it’ll be as helpful to the city as it will be to the citizens of the city,” Rosenauer said.