Hamilton said her daughter, who is now a senior at CISD’s Smithson Valley High School, had a difficult time adjusting to the changes to her routine, learning methods and environment.

“She really struggled with the fact that, here I am trying to give her school work to do, and she’s looking at me like, ‘No mom, this is home; this is when I have my chance to relax and do my own thing,’” she said.

For students who are enrolled in special education programs and receiving additional support for dyslexia and other learning disabilities, in-person and one-on-one instruction are critical, Hamilton said. Data and experience from local education professionals back up that assertion.

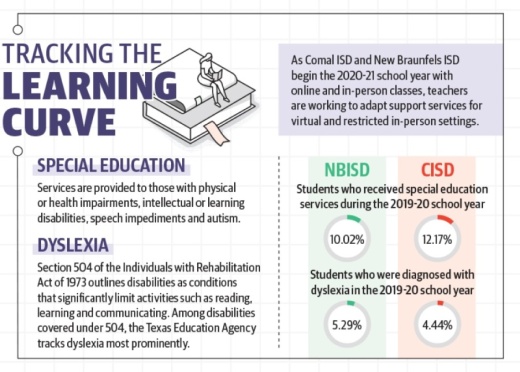

During the 2019-20 school year, 10.02% of students in NBISD and 12.17% of students in CISD received special education services.

Additionally, 5.29% of students in NBISD and 4.44% of students in CISD were diagnosed with dyslexia, according to the Texas Education Agency.

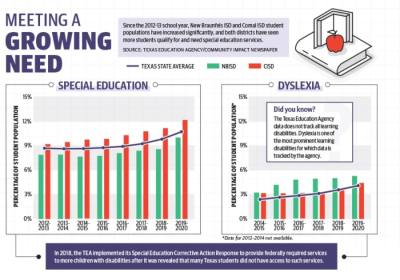

Furthermore, since the 2012-13 school year, TEA data shows the percentage of students receiving special education services has jumped by more than 2% in each district.

“We have seen an increase in the percentage of special education students in the district,” said Martha Moke, executive director of special education for NBISD, in an email. “I believe this is due to the change in mindset that resulted from our state having to put a corrective action plan in place and as a result of our parents making more requests and our campuses pushing referrals a little earlier.”

In 2018, the TEA implemented its Special Education Corrective Action Response in an effort to provide federally required services to children with disabilities after it was revealed that many Texas students did not have access to such services.

In order to receive services, students must be evaluated each year by an admission, review and dismissal committee that determines a child’s eligibility for services and develops his or her Individual Education Program, or IEP.

When schools closed in March, special education teachers in both districts had to adjust IEPs to online instruction, and many struggled to translate their teaching techniques to virtual platforms.

“The second half of the spring semester was tough,” said Yesenia Aguilar, an Essential Academics teacher at CISD's Smithson Valley High School, in an email. “I had never created a digital lesson prior to March. I had absolutely no experience. ... I have a few students who require physical prompting ... to access the curriculum or retain information.”

Planning for a safe fall semester

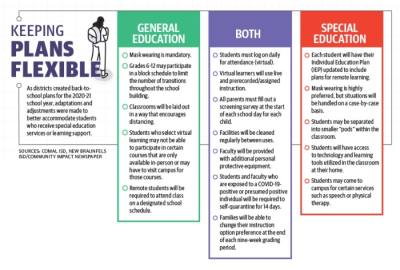

In July, both school districts announced plans to begin the 2020-21 school year with online and in-person schooling options that allowed parents to select an instruction method at the end of each nine-week grading period. NBISD began the school year on Aug. 24, and CISD began on Aug. 25.

The decision came after months of planning meetings between school administration leaders, campus leaders, and other local and state education entities, said Michele Martella, executive director of special education services for CISD.

“I saw a lot of cross-district collaboration,” Martella said. “In the big context, special ed was always a part of the awareness that this group of children wasn’t an afterthought.”

Martella said she and her colleagues met regularly to discuss district plans and ideas for how to adjust on-campus and online learning for students receiving special education services. Teachers utilized summer programming to try new instruction methods and analyzed what did and did not work, she said.

“The children with the most complex needs are the kids that we’ve focused a lot of attention on, because if they’re not going to come back on campus, we need to think of a different way to engage those children,” Martella said.

Evaluations for students receiving services resumed in July for CISD and in August for NBISD, according to information from both districts.

Each student’s IEP will also include a contingency plan should the student have to transition from in-person to online learning at any time during the school year.

Included in these remote learning plans are allowances for assisted technology devices, such as text-to-speech systems, to be sent home with students, instructional calls between parents and teachers to help guide parents through lessons, and opportunities for students to visit campuses once or twice a week for specialized support.

For students who attend school in person, many of the same safety and distancing protocols implemented in general education classes will be encouraged, but more attention will be given to individual cases, according to district plans.

“Students and staff will be asked to wear masks just like all other students and staff,” Moke said in an email. “We do have some students that will have a difficult time tolerating the mask, so teachers and staff will put individualized plans in place to help students become accustomed to wearing a mask.”

Moke and Martella both said teachers may divide classes into smaller groups to encourage distancing in the classroom, create spaces where students can take mask breaks if needed and use positive reinforcement to encourage mask wearing.

“It’s just a skill they would need in the community,” Martella said. “[That’s] why we’re trying so hard to get kids to build stamina to be able to wear it as developmentally appropriate.”

Parents hope in-person instruction will offer support

At NBISD, approximately 65% of students who receive special education services requested to begin the school year in person, while approximately 60% of CISD students receiving services requested to be in person.

Since online learning began in March, many parents have publicly vocalized their dislike for that approach. Students lost skills they had been practicing in school.

“With all students, we worry about regression of skills learned. Without practice, some skills get lost. Teachers and students will need to spend time recouping those skills, in conjunction with building new ones,” Michelle Mouton wrote in an email.

Mouton is a Preschool Programs for Children with Disabilities teacher at CISD’s Morningside Elementary School and has a son who receives special services.

“I’ve seen this with my own son. He is high functioning on the autism spectrum. We have worked very hard teaching him how to filter his words,” Mouton wrote, adding that her son will have to relearn in a face-to-face situation much of what he has forgotten since switching to online learning.

Jamie Rosales, whose daughter has been diagnosed with a rare genetic disorder called William’s Syndrome and is a senior at CISD’s Canyon High School, said she felt it was necessary to choose in-person instruction so that her children could have access to services and regain routine.

“There was no choice. We have to send our kids back, because if we don’t, they’re not going to get what they need,” Rosales said. “They need the intervention. They need the service. They need the help. They need structure. She thrives on it.”

Along with her daughter, Hamilton said she also decided to send her son, a freshman at Smithson Valley High school, to in-person classes so her daughter could receive specialized services and her son could participate in electives such as theater and the debate team.

Rosales and Hamilton also shared that their children need face-to-face instruction in order to keep learning and thriving in an educational environment.

“My hope is that our kids can get back to something normal, because they need it,” Rosales said. “From my senior to my second grader, they are craving human interaction.”