But something happened around the middle of 2020 that led the market to take off, according to Realtors and economists.

Due to the increase in telework brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, they said, many newly remote workers moved in from other, more expensive, cities, no longer tied to their commutes. Locally, employees using their homes as office space thought differently about their needs. While unemployment levels reached the double digits nationwide, those who did keep their jobs built up disposable income.

“We were the hottest market, and we essentially dumped gasoline on it,” Bramlett said.

Before April 2021, the monthly median sale price of a home in New Braunfels had never broken the $290,000 mark, according to data tracked by the Four Rivers Association of Realtors. The median price rose to $295,001 in April 2021, and in May, the most recent month available, the median sale price for homes sold in the city was $316,228.

Those incredibly rapid price increases are creating an affordability challenge, according to James Gaines, research economist with Texas A&M University’s Texas Real Estate Center.

“You don’t have to have a Ph.D in economics to understand that if prices go up faster than incomes, and home affordability is based on the relationship between income and price, then [homeownership is] becoming less affordable,” Gaines said.

That breakneck pace of price increase cannot last forever, according to Patricia Fernandez, 2021 president of the Four Rivers Association of Realtors. Eventually, Fernandez said she expects the price to return to some level of normalcy, although that could take years as supply catches up with demand.

“Builders are building as fast as they can, but you know that still takes time. It’s ... not an easy process.” Fernandez said. “I mean, it takes years for development just to get the groundwork done.”

‘Perfect storm’ of construction challenges

Even with demand potentially leveling off after the pandemic as individuals begin reprioritizing their spending habits, increasing supply remains difficult for many builders.

Aaron Boenig is the co-president of Brohn Homes, a developer that focuses on homes that are in the price range for first-time homebuyers. The company builds homes from Georgetown to Bastrop to San Marcos—areas less expensive than Austin—but Boenig said it is increasingly difficult to build at a mid-range price point even in outlying areas.

Land prices are one factor making it harder for developers to build affordable homes, but Boenig said buying the land is only one challenge. Long waits for building permit approvals, the jump in materials prices—especially lumber—and labor shortages are also affecting developers. Boenig called it a “perfect storm” that is restricting supply.

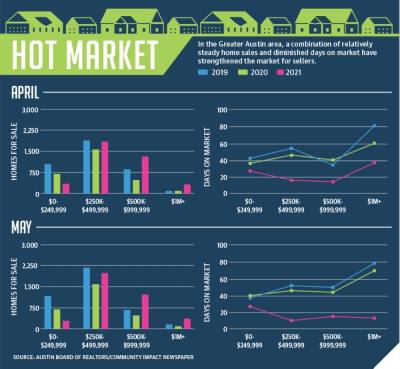

In the Austin metro as of May, there was 1.3 months of inventory available, according to the Austin Board of Realtors. Months of inventory is a measure of how long it would take to sell all existing properties on the market. A balanced market, according to Gaines, has about five to seven months of inventory.

“I think this is unprecedented, the way builders are selling homes; I’ve never seen anything like it in this industry,” Boenig said.

Alternatives to single family

Adrianne Craft, a real estate broker who is licensed with Keller Williams Realty, said buyers are having a truly difficult time finding homes—and not just in the Hays and Comal county areas where she is largely focused.

“A year ago, I would say that buyers could be a little bit pickier as far as the condition of a home goes,” Craft said. “A buyer may choose a house over another house because it doesn’t have carpet, or it has white cabinets. ... Whereas now, buyers are having to just concede on everything.”

Craft added that every deal she has brokered this year has seen multiple offers for which homes are typically selling for 10%-20% over asking price. This is a situation that frequently does not favor first-time buyers, especially those seeking single-family homes, which account for the vast majority of homes on the market at any given time, she said.

One solution officials in cities throughout the Greater Austin area have been examining over the last several years involves diversification of home types. Dan Parolek, CEO of Opticos Design, a California firm that helps collaborate on housing and community issues, has given many presentations to city officials throughout Central Texas, from New Braunfels to Austin.

Parolek’s presentations center on a concept called missing middle housing, which involves homes from duplexes to townhouses to buildings with eight units, and which are walkable, or located near business or city centers that have popular amenities.

These options, Parolek said, offer more affordability for people including first-time buyers who cannot make cash offers in order to become homeowners.

“Every market, regardless of how big the city, has been impacted pretty dramatically by the increase in costs,” Parolek said. “It’s become harder for ... sort of entry-level households to purchase homes.”

While Parolek agrees that single-family homes are the most abundant option for homebuyers, he said polling has shown that they are not necessarily the most popular option. He added that through his own research, national data show that 60% of all housing will need to be missing middle housing by 2040 in order to keep up with demand.

“I think there will continue to be a demand for single-family detached [homes], but I think more and more, there is a growing demand that is not being met for these missing middle housing types,” he said. “I’m not saying there is not a demand for single-family, but historically that is all we’ve been delivering, and the industry is having a hard time sort of adjusting and shifting quickly enough to meet the demand.”

Smaller cities see big growth

When Robin Sheppard sold her home of 35 years in Austin in December 2020, she did not anticipate that she would still be searching for a house more than six months later.

Increasing tax rates, heavy traffic and rapid growth within Austin played a key role in Sheppard’s decision to leave the capital and move to San Marcos. She would still be close enough to visit friends but in a less crowded city, she said.

“I had lived in Houston for many years, and I left there to come to Austin because Austin was a lot smaller and had a wonderful feel to it,” Sheppard said. “This is not the Austin I came to.”

Within 2 1/2 days of listing her home, Sheppard received seven bids and accepted an offer that was $50,000 over asking and included a contingency that allowed her to live in her home rent-free for 30 days after closing.

“I just thought, ‘Wow, this is great; now I can go and buy myself a house and have extra left over to travel,’ ... but that wasn’t the way it was,” she said.

By June, Sheppard had placed bids on more than six properties that met her requirement for an accessory dwelling unit she plans to rent for a low cost to a friend. Despite her multiple offers on several properties, including one that clocked in at $42,000 over asking, she has been outbid every time.

Many who plan to move to one of the smaller cities along the I-35 corridor expect to find more availability at a lower price point than in larger metro areas, Fernandez said.

However, skyrocketing demand and dwindling supply have made once affordable markets highly competitive.

“You can pick any town in this corridor, and it’s the same story,” Fernandez said, adding buyers who qualified at one point for a house worth $350,000, for example, may have to place bids for homes listed in the high $200,000 range with the expectation of paying significantly more. “That whole middle market [is] just now getting wiped out of the playing field.”

As the population growth of cities on I-35 continues to outpace supply and corporations such as Amazon and Tesla invest in Central Texas, Fernandez expects to see interest grow in towns east of the interstate.

“[East] is the only direction you can go right now, because even as far as Waco it is the same exact market we are having,” Fernandez said.

Some buyers looking to live in a specific city are opting to purchase a home that is not yet built and rent until their house is complete.

Laurianne Rodriguez is originally from New Braunfels, and after her husband was assigned to Randolph Air Force Base in San Antonio for his last assignment, her family contracted with a builder in February for a home under construction in her hometown.

“We contracted early, and we are extremely grateful we did, because there’s a point at which we would have already been priced out of our house,” Rodriguez said.

Due to climbing construction costs, the price to contract the same model in June has jumped by $125,000, according to Rodriguez.

Until their home is complete, the family is renting in New Braunfels so their children can begin school in the same school district as their new house. Finding a rental for a family of four was difficult, Rodriguez said, and she hopes to be able to move in within a year. If Sheppard, who is still trying to find a house in San Marcos, cannot purchase one in the next month, she said she would also search for a rental property.

“I feel like I’m homeless, you know; it just doesn’t feel good,” Sheppard said. “At the end of this month if I don’t have [a house], then I will rent something. ... I’m not looking forward to that, but that’s certainly going to have to be the next step. I can’t indefinitely be staying in other people’s homes.”